Navajo phonology

Encyclopedia

Navajo phonology is the study of how speech sounds pattern and interact with each other in that language. The phonology

of Navajo

is intimately connected to its morphology

. For example, the entire range of contrastive consonants is found only at the beginning of word stems. In stem-final position and in prefixes, the number of contrasts is drastically reduced. Similarly, vowel contrasts (including their prosodic combinatory possibilities) found outside of the stem are significantly neutralized.

Like most Athabascan languages, Navajo is coronal

heavy, having many phonological contrasts at coronal places of articulation and less at other places. Also typical of the family, Navajo has a limited number of labial sounds, both in terms of its phonemic inventory and in their occurrence in actual lexical items and displays of consonant harmony

.

of the aspirated and ejective stops is twice as long as that found in most non-Athabaskan languages. Young and Morgan described Navajo consonants as "doubled" between vowels, but in fact they are equally long in all positions (McDonough & Ladefoged 1993).

Stops and affricates. All stops and affricates, except for the bilabial and glottal, have a three-way laryngeal contrast between unaspirated, aspirated, and ejective. The labials /p, m/ are found in only a few words. Most of the contrasts in the inventory lie within coronal territory at the alveolar and palatoalveolar places of articulation.

The aspirated stops /tʰ, kʰ/ (orthographic , ) are typically aspirated with velar frication [tx, kx] (they are phonetically affricates — homorganic in the case of [kx], heterorganic in the case of [tx]). The velar aspiration is also found on a labialized velar [kxʷ] (orthographic ). There is variation within Navajo, however, in this respect: some dialects lack strong velar frication having instead a period of aspiration.

Similarly the unaspirated velar /k/ (orthographic ) is realized as with optional voiced velar frication following the stop burst: [k] ~ [kɣ]. The unaspirated lateral /tɬ/ (orthographic ) typically has a voiced lateral release

, [tˡ], of a duration comparable to the release of the /k/ and much shorter than the unaspirated fricatives /ts/, /tʃ/. However, the aspirated and ejective laterals are true fricatives.

While the aspiration of stops is markedly long compared to most other languages, the aspiration of the affricates is quite short: the main feature distinguishing /ts/ and /tʃ/ from /tsʰ/ and /tʃʰ/ is that the frication is half again as long in the latter: [tsˑʰ], [tʃʰˑ]. /tɬʰ/ is similarly long, [tɬˑʰ]. The ejectives /tsʼ/, /tɬʼ/, /tʃʼ/, on the other hand, have short frication, presumably due to the lack of pulmonic airflow

. There is a period of near silence before the glottalized onset of the vowel. In /tɬʼ/ there may be a double glottal release, or a creaky

onset to the vowel not found in the other ejective affricates.

Continuants. Navajo voiceless continuants are realized as fricatives. They are typically noisier than the fricatives that occur in English. The palato-alveolars /ʃ, ʒ/ are not labialized unlike English and other European languages (McDonough 2003: 130).

Navajo also does not have consistent phonetic voicing in the "voiced" continuant members. Although [z, l, ʒ, ɣ] are described as voiced in impressionist descriptions (such as Hoijer 1945a), data from spectrogram

s shows that they may be partially devoiced during the constriction. In stem-initial position, /l/ tends to be fully voiced, /ʒ/ has a slight tendency to be voiceless near the offset, /z/ is often mostly voiceless with phonetic voicing only at the onset, /ɣ/ is also only partially voiced with voicing at onset. A more consistent acoustic correlate of the "voicing" is the duration of the consonant: "voiceless" consonants have longer durations than "voiced" consonants. Based on this, McDonough 2003 argues that the distinction is better captured with the notion of a fortis/lenis contrast. A further characteristic of voicing in Navajo is that it is marginally contrastive. (See the voicing assimilation section.)

Navajo lacks a clear distinction between phonetic fricatives and approximants. Although the pair [ɬ] : [l] has been described as a fricative and an approximant, respectively, the lack of a consistent contrast between the two phonetic categories and a similar patterning with other fricative pairs suggests that they are better described as continuants. Additionally, observations have been made about the less fricative-like nature of [ɣ, ɣʷ] and the more fricative-like nature of [j].

Sonorants. A more abstract analysis of Navajo posits two different /j/ phonemes. (See the Velar /ɣ/, palatal /j/ for elaboration.)

The glottalized sonorants are the result of d-effect on the non-glottalized counterparts. (See the d-effect section for further explanation.) A strict structuralist analysis, such as that of Hoijer (1945a) and Sapir & Hoijer (1967), considers them phonemic.

Glottal(ized) consonants. Consonants involving a glottal closure — the glottal stop, ejective stops, and the glottalized sonorants — may have optional creaky voice

on voiced sounds adjacent to the glottal gesture. Glottal stops may also be realized entirely as creaky voice instead of single glottal closure. Ejectives in Navajo differ from the ejectives in many other languages in that the glottal closure is not released near-simultaneously with the release of the oral closure (as is common in other languages) — it is held for a significant amount of time following oral release. The glottalized sonorants /mʼ, nʼ/ are articulated with a glottal stop preceding the oral closure with optional creaky voice during the oral closure: [ʔm ~ ʔm̰, ʔn ~ ʔn̰].

Labialized consonants. Consonants /kʰʷ, xʷ, ɣʷ, hʷ/ are predictable variants that occur before the rounded oral vowel /o/. However, these sounds also occur before the vowels /i, e, a/ where they contrast with their non-labialized counterparts /kʰ, x, ɣ, h/.

Before the rounded /o/, /ɣ/ is phonetically strongly labialized as [ɣʷ]; elsewhere, it lacks the labialization. As noted above, the lenis continuants like /ɣ/ are often very weak fricatives somewhere between a typical fricative constriction (e.g. [ɣ]) and a more open approximant constriction (e.g. [ɰ]) — this will be symbolized here as [ɰ̝]. Hoijer (1945a) describes the [ɰ̝ʷ] realization as being similar to English [w] but differing in having slight frication at the beginning of the articulation. The realization before /a/ varies between an approximant [ɰ] and a weakly fricated approximant [ɰ̝]. The following verb stem has different velar allophones of the stem-initial consonant:

The palatal glide /j/ is also phonetically between an approximant [j] and a fricative [ʝ]. Hoijer (1945a) compares it to English [j] with a "slight but audible 'rubbiness' or frication".

The contrast between velar /ɣ/ and palatal /j/ is found before both back vowels /a, o/ as the following contrasts demonstrate:

Before the front vowels /i, e/, however, the contrast between /ɣ/ and /j/ is neutralized to a palatal articulation much like the weakly fricative [j˔] realization of /j/ that occurs before back vowels. However, the underlying consonant can be ascertained in verb stems and noun stems via their different realizations in a voiceless (i.e. fortis) context. The underlying velar surfaces as a voiceless palatal fricative [ç] in these environments:

The stem-initial velar of the noun stem /xéːɬ/ has a voiceless fortis realization of [ç] (as [çéːɬ]) when word-initial. When intervocalic, it is realized as lenis [j˔] (as [-j˔éːl]). Likewise, the underlying velar of the verb stem /xɪ̀ʒ/ is a voiceless [ç] after the preceding voiceless [ʃ] and lenis [j˔] when intervocalic. Thus, the alternation of [ç ~ j˔] in the two contexts is indicative of an underlying velar consonant. Similarly before the back vowels, the velar continuant has the alternations [x ~ ɰ̝] and [xʷ ~ ɰ̝ʷ] as shown in the examples below:

An underlying palatal /j/ can determined by alternations which differ from the velar alternations. However, /j/ has two different alternation patterns which have led to the positing of two distinct phonemes. Incidentally, the two different phonemes are also connected to two different reconstructed consonants in Proto-Athabascan. One of these /j/ phonemes is considered an obstruent as it has a fricative realization of [s] in fortis contexts. It is often symbolized as a palatalized (or front velar) fricative (in Americanist

phonetic notation) and is a reflex of Proto-Athabascan . It may be considered coronal because of its coronal voiceless allophone.

In the above examples, the fortis realization is [s] in the stems [sɪ̀n], [-sã́], [-sóːt] while the lenis realization is the glide [j˔] in the corresponding [-j˔ɪ̀n], [-j˔ã́], [-j˔óːt].

The other underlying (or morphophonemic) palatal /j/ is considered a sonorant and has an invariant [j˔] realization in both fortis (voiceless) and lenis (voiced) contexts. This phoneme is relatively rare, occurring in only a few morpheme

s. It is a reflex of Proto-Athabascan (as symbolized in Americanist notation). Two examples are below:

A further distinction between the different phonemes are found in the context of d-effect (for which, see the d-effect section).

The varying contextual realizations of these three underlying segments are summarized in the following table:

Since the voicing is predictable, it can be represented more abstractly as an underlying

consonant that is underspecified with respect to voicing. These archiphonemes can be indicated with the capital letters /Z, L, Ʒ, Ɣ/. The variant voicing of the stem-initial consonant can be found in the context of subject person prefixes which are added to the verb stem:

As the above examples show, the stem-initial consonant is voiced when intervocalic and voiceless when it is preceded by a voiceless /ʃ-/ first person singular subject prefix or a voiceless [h] in the /oh-/ two person dual subject prefix.

Another example of contextual voicing of verb-stem-initial consonants occurs when a voiceless /-ɬ-/ classifier prefix occurs before the stem as in the following:

In the verb-form [tìːlzáːs] "we two dribble it along", the /Z/ occurs between a voiced [l] and the voiced stem vowel [áː]. Thus it is realized as a voiced [z]. Here the /-ɬ-/ classifier is voiced due to the d-effect of the preceding /Vt-/ first person dual subject prefix. (See the section on Navajo d-effect for further explanation.) In the other verb-forms, the stem-initial /Z/ is preceded by voiceless /-ɬ-/ classifier which results in a voiceless realization of [s]. In the surface verb-forms, the underlying /-ɬ-/ classifier is not pronounced due to a phonotactic restriction on consonant clusters.

The initial consonant of noun stems also display contextual voicing:

Here an intervocalic context is created by inflecting the nouns , , , with a [pɪ̀-] third person prefix which ends in a vowel. In this context, the stem-initial consonant is voiced. When these nouns lack a prefix (in which case the stem-initial consonant is word-initial), the realization is voiceless.

However, in some noun stems, the stem-initial continuant does not voice when intervocalic: [ʔàʃĩ̀ːh] "salt".

s /k, kʰ, kʼ, x, ɣ/ (orthographic , , , , ) have contextual phonetic variants (i.e. allophone

s) varying along place of articulation

that depend on the following vowel environment. They are realized as palatals before the front vowels and and as velars before the back vowels and . Additionally, they are labialized before the rounded back vowel o. This likewise happens with the velar frication of the aspirated /tʰ/.

sibilant consonant harmony

. Alveolar sibilants in prefixes assimilate

to post-alveolar sibilants in stems, and post-alveolar prefixal sibilants assimilate to alveolar stem sibilants. For example, the si- stative perfective is realized as si- or shi- depending upon whether the stem contains a post-alveolar sibilant:

(or mutation

) occurring in Athabascan languages called d-effect is found in Navajo. The alternation in most cases is a fortition

(or strengthening) process. The initial consonant of a verb stem alternates with a strengthened consonant when it is preceded by a /-t-/ (orthographic ) "classifier" prefix or the /-Vt-/ first person dual subject prefix. The underlying /t/ of these prefixes is absorbed into the following stem. D-effect can be viewed prosodically as the result of a phonotactic constraint on consonant clusters that would otherwise result from the concatenation of underlying segments (McDonough 2003: 60). There is thus an interaction between a requirement for the grammatical information to be expressed in the surface form and an avoidance of having sequences of consonants. (See the syllable section for more on phonotactics.)

The fortition is typically a change from continuant to affricate or continuant to stop (i.e. adding a period of closure to the articulation). However, other changes involve glottalization of the initial consonant:

The two occurrences of t- + -j in the chart above reflect two different patterns of d-effect involving stem-initial /j/. Often different underlying consonants are posited to explain the different alternation. The first alternation is posited as a result of underlying t- + -ɣ leading to a d-effect mutation of /dz/. The other is t- + -j resulting in /jˀ/. (See the velar /ɣ/, palatal /j/ section for further explanation.)

Another example of d-effect influences not the stem-initial consonant but the classifier prefix. When the /-Vt-/ first person dual subject prefix precedes the /-ɬ-/ (orthographic ) classifier prefix, the /-ɬ-/ classifier is realized as voiced [l]:

qualities [i, e, o, ɑ] at three different vowel heights (high, mid, low) and a front-back contrast between the mid vowels [e, o]. There are also two contrastive vowel length

s and a contrast in nasalization

. This results in 16 phonemic vowels, shown below.

There is a phonetic vowel quality difference between the long high vowel /iː/ (orthographic ) and the short high vowel /i/ (orthographic ): the shorter vowel is significantly lower at [ɪ] than its long counterpart. This phonetic difference is salient to native speakers, who will consider a short vowel at a higher position to be a mispronunciation. Similarly, short /e/ is pronounced [ɛ]. Short /o/ is a bit more variable and more centralized, covering the space [ɔ] ~ [ɞ]. Notably, the variation in /o/ does not approach [u], which is a true gap in the vowel space.

Although the nasalization is contrastive in the surface phonology, many instances of nasalized vowels can be derived from a sequence of Vowel + Nasal consonant in a more abstract analysis. Additionally, there are alternations between long and short vowels that are predictable.

There have been a number of somewhat different descriptions of Navajo vowels, which are conveniently summarized in McDonough (2003).

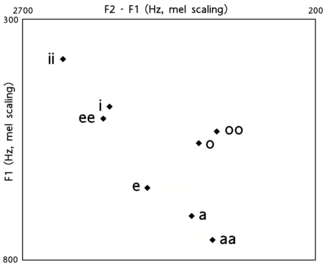

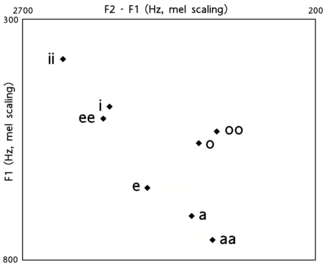

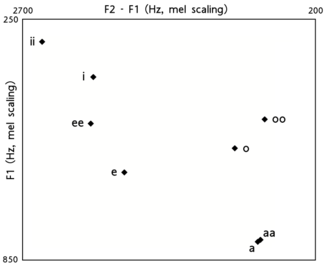

McDonough (2003) has acoustic measurements of the formant

McDonough (2003) has acoustic measurements of the formant

s of Navajo long and short vowel pairs as pronounced by 10 female and 4 male native speakers. Below are the median

values of the first (F1) and second (F2) formants for this study.

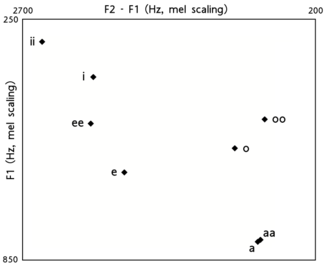

An earlier study (McDonough et al. 1993) has measurements from 7 females:

s: high and low. Orthographically, high tone is marked with an acute accent

(á) over the affected vowel, while low tone is left unmarked (a). This reflects the tonal polarity of Navajo, as syllables have low tone by default.

Long vowels normally have level tones (áá, aa). However, in grammatical contractions

and in Spanish loan words such as "money" (from Spanish ), long vowels may have falling (áa) or rising (aá) tones.

The sonorant n also carries tone when it is syllabic. Here again, the high tone is marked with an acute (ń) while the low tone is left unmarked (n).

Despite the fact that low tone is the default, these syllables are not underspecified for tone: they have a distinct phonetic tone, and their pitch is not merely a function of their environment. This contrasts with the related Carrier language

. As in many languages, however, the pitches at the beginnings of Navajo vowels are lower after voiced consonants than after tenuis and aspirated consonants. After ejective consonants, only high tones are lowered, so that the distinction between high and low tone is reduced. However, the type of consonant has little effect on the pitch in the middle of the vowel, so that vowels have characteristic rising pitches after voiced consonants.

The pitch of a vowel is also affected by the tone of the previous syllable: in most cases, this is has as great an effect on the pitch of a syllable as its own tone. However, this effect is effectively blocked by an intervening aspirated consonant. (deJong & McDonough 1993)

In verbs, with few exceptions, only stems

may carry a high tone: onsonant. Prefixes are mostly single consonants, C-, and do not carry tone. The one exception is the high-tone vocalic prefix /ʌ́n/-. Most other tone-bearing units in the Navajo verb are second stems or clitic

s.

All Navajo verbs can be analyzed as compounds, and this greatly simplifies the description of tone. There are two obligatory components, the "I" stem (for "inflection") and the "V" stem (for "verb"), each potentially bearing a high tone, and each preceded by its own prefixes. In addition, the compound as a whole takes 'agreement' prefixes like the prefixes found on nouns. This entire word may then take proclitics, which may also carry tone:

(Hyphens – mark prefixes, double hyphens = mark clitics, and plus signs + join compounds.)

Any high tones on clitics and the prefix /ʌ́n/- spread to the next syllable of the word. This spreading is blocked by long vowels, as can be seen with the iterative clitic /ná/꞊. Compare

and

where the clitic ná= creates a high tone on the following syllable, but,

where it does not.

types:

That is, all syllables must have a consonant onset C, a vowel nucleus V. The syllable may carry a high tone T, the vowel nucleus may be short or long, and there may optionally be a consonant coda

.

Prefixes. Prefixes typically have a syllable structure of CV-, such as chʼí- "out horizontally". Exceptions to this are certain verbal prefixes, such as the classifiers (-ł-, -l-, -d-) that occur directly before the verb stem, which consist of a single consonant -C-. A few other verbal prefixes, such as naa- "around, about" on the outer left edge of the verb have long vowels, CVV-. A few prefixes have more complex syllable shapes, such as hashtʼe- "ready, prepared" (CVCCV-). Prefixes do not carry tone.

In some analyses, such as that of Harry Hoijer

, consider conjunct verbal prefixes to have the syllable shape CV-. In other generative analyses (e.g. McDonough 2003), the same prefixes are considered to have only underlying consonants of the shape C-. Then, in certain environments, an epenthetic vowel (the default vowel is i) is inserted after the consonantal prefix.

used the term pepet vowel). For example, the verb meaning "she/he/they is/are crying" has the following morphological composition: Ø-Ø-cha where both the imperfective modal prefix and the third person subject prefix are phonologically null morpheme

s and the verb stem is -cha. In order for this verb to be complete a yi- peg element must be prefixed to the verb stem, resulting in the verb form yicha. Another examples are verb yishcha "I'm crying" which is morphologically Ø-sh-cha (Ø- null imperfective modal, -sh- first person singular subject, -cha verb stem) and wohcha "you (2+) are crying" which is Ø-oh-cha (Ø- null imperfective modal, -oh- second person dual-plural subject, -cha verb stem). The glide

consonant of the peg element is y before i, w before o, and gh before a.

Phonology

Phonology is, broadly speaking, the subdiscipline of linguistics concerned with the sounds of language. That is, it is the systematic use of sound to encode meaning in any spoken human language, or the field of linguistics studying this use...

of Navajo

Navajo language

Navajo or Navaho is an Athabaskan language spoken in the southwestern United States. It is geographically and linguistically one of the Southern Athabaskan languages .Navajo has more speakers than any other Native American language north of the...

is intimately connected to its morphology

Morphology (linguistics)

In linguistics, morphology is the identification, analysis and description, in a language, of the structure of morphemes and other linguistic units, such as words, affixes, parts of speech, intonation/stress, or implied context...

. For example, the entire range of contrastive consonants is found only at the beginning of word stems. In stem-final position and in prefixes, the number of contrasts is drastically reduced. Similarly, vowel contrasts (including their prosodic combinatory possibilities) found outside of the stem are significantly neutralized.

Like most Athabascan languages, Navajo is coronal

Coronal consonant

Coronal consonants are consonants articulated with the flexible front part of the tongue. Only the coronal consonants can be divided into apical , laminal , domed , or subapical , as well as a few rarer orientations, because only the front of the tongue has such...

heavy, having many phonological contrasts at coronal places of articulation and less at other places. Also typical of the family, Navajo has a limited number of labial sounds, both in terms of its phonemic inventory and in their occurrence in actual lexical items and displays of consonant harmony

Consonant harmony

Consonant harmony is a type of "long-distance" phonological assimilation akin to the similar assimilatory process involving vowels, i.e. vowel harmony.-Examples:...

.

Consonants

The consonant phonemes of Navajo are listed below.| Bilabial Bilabial consonant In phonetics, a bilabial consonant is a consonant articulated with both lips. The bilabial consonants identified by the International Phonetic Alphabet are:... |

Alveolar Alveolar consonant Alveolar consonants are articulated with the tongue against or close to the superior alveolar ridge, which is called that because it contains the alveoli of the superior teeth... |

Palato- alveolar Palato-alveolar consonant In phonetics, palato-alveolar consonants are postalveolar consonants, nearly always sibilants, that are weakly palatalized with a domed tongue... |

Palatal Palatal consonant Palatal consonants are consonants articulated with the body of the tongue raised against the hard palate... |

Velar Velar consonant Velars are consonants articulated with the back part of the tongue against the soft palate, the back part of the roof of the mouth, known also as the velum).... |

Glottal Glottal consonant Glottal consonants, also called laryngeal consonants, are consonants articulated with the glottis. Many phoneticians consider them, or at least the so-called fricative, to be transitional states of the glottis without a point of articulation as other consonants have; in fact, some do not consider... |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | lateral Lateral consonant A lateral is an el-like consonant, in which airstream proceeds along the sides of the tongue, but is blocked by the tongue from going through the middle of the mouth.... |

fricated Affricate consonant Affricates are consonants that begin as stops but release as a fricative rather than directly into the following vowel.- Samples :... |

plain | labial Labial consonant Labial consonants are consonants in which one or both lips are the active articulator. This precludes linguolabials, in which the tip of the tongue reaches for the posterior side of the upper lip and which are considered coronals... |

plain | labial Labial consonant Labial consonants are consonants in which one or both lips are the active articulator. This precludes linguolabials, in which the tip of the tongue reaches for the posterior side of the upper lip and which are considered coronals... |

||||||

| Obstruent Obstruent An obstruent is a consonant sound formed by obstructing airflow, causing increased air pressure in the vocal tract, such as [k], [d͡ʒ] and [f]. In phonetics, articulation may be divided into two large classes: obstruents and sonorants.... |

Stop Stop consonant In phonetics, a plosive, also known as an occlusive or an oral stop, is a stop consonant in which the vocal tract is blocked so that all airflow ceases. The occlusion may be done with the tongue , lips , and &... |

unaspirated Tenuis consonant In linguistics, a tenuis consonant is a stop or affricate which is unvoiced, unaspirated, and unglottalized. That is, it has a "plain" phonation like , with a voice onset time close to zero, as in Spanish p, t, ch, k, or as in English p, t, k after s .In transcription, tenuis consonants are not... |

p | t | tˡ | ts | tʃ | k | ʔ | |||

| aspirated Aspiration (phonetics) In phonetics, aspiration is the strong burst of air that accompanies either the release or, in the case of preaspiration, the closure of some obstruents. To feel or see the difference between aspirated and unaspirated sounds, one can put a hand or a lit candle in front of one's mouth, and say pin ... |

tʰ | tɬʰ | tsʰ | tʃʰ | kʰ | (kʷʰ) | ||||||

| ejective Ejective consonant In phonetics, ejective consonants are voiceless consonants that are pronounced with simultaneous closure of the glottis. In the phonology of a particular language, ejectives may contrast with aspirated or tenuis consonants... |

tʼ | tɬʼ | tsʼ | tʃʼ | kʼ | |||||||

| Continuant Continuant A continuant is a sound produced with an incomplete closure of the vocal tract. That is, any sound except a stop or nasal. An affricate is considered to be a complex segment, composed of both a stop and a continuant.-See also:... |

fortis | ɬ | s | ʃ | x | (xʷ) | (h) | (hʷ) | ||||

| lenis | l | z | ʒ | ɣ | (ɣʷ) | |||||||

| Sonorant Sonorant In phonetics and phonology, a sonorant is a speech sound that is produced without turbulent airflow in the vocal tract; fricatives and plosives are not sonorants. Vowels are sonorants, as are consonants like and . Other consonants, like or , restrict the airflow enough to cause turbulence, and... |

Nasal Nasal consonant A nasal consonant is a type of consonant produced with a lowered velum in the mouth, allowing air to escape freely through the nose. Examples of nasal consonants in English are and , in words such as nose and mouth.- Definition :... |

plain | m | n | ||||||||

| glottalized Glottalization Glottalization is the complete or partial closure of the glottis during the articulation of another sound. Glottalization of vowels and other sonorants is most often realized as creaky voice... |

(mʼ) | (nʼ) | ||||||||||

| Glide Approximant consonant Approximants are speech sounds that involve the articulators approaching each other but not narrowly enough or with enough articulatory precision to create turbulent airflow. Therefore, approximants fall between fricatives, which do produce a turbulent airstream, and vowels, which produce no... |

plain | j | (w) | |||||||||

| glottalized | (jʼ) | (wʼ) | ||||||||||

Phonetics

All consonants are long, compared to English: with plain stops the hold is longer, with aspirated stops the aspiration is longer, and with affricates the frication is longer. The voice onset timeVoice onset time

In phonetics, voice onset time, commonly abbreviated VOT, is a feature of the production of stop consonants. It is defined as the length of time that passes between when a stop consonant is released and when voicing, the vibration of the vocal folds, or, according to the authors, periodicity begins...

of the aspirated and ejective stops is twice as long as that found in most non-Athabaskan languages. Young and Morgan described Navajo consonants as "doubled" between vowels, but in fact they are equally long in all positions (McDonough & Ladefoged 1993).

Stops and affricates. All stops and affricates, except for the bilabial and glottal, have a three-way laryngeal contrast between unaspirated, aspirated, and ejective. The labials /p, m/ are found in only a few words. Most of the contrasts in the inventory lie within coronal territory at the alveolar and palatoalveolar places of articulation.

The aspirated stops /tʰ, kʰ/ (orthographic , ) are typically aspirated with velar frication [tx, kx] (they are phonetically affricates — homorganic in the case of [kx], heterorganic in the case of [tx]). The velar aspiration is also found on a labialized velar [kxʷ] (orthographic ). There is variation within Navajo, however, in this respect: some dialects lack strong velar frication having instead a period of aspiration.

Similarly the unaspirated velar /k/ (orthographic ) is realized as with optional voiced velar frication following the stop burst: [k] ~ [kɣ]. The unaspirated lateral /tɬ/ (orthographic ) typically has a voiced lateral release

Lateral release (phonetics)

In phonetics, a lateral release is the release of a plosive consonant into a lateral consonant. Such sounds are transcribed in the IPA with a superscript ⟨l⟩, for example as . In English words such as middle in which, historically, the tongue made separate contacts with the alveolar ridge for the ...

, [tˡ], of a duration comparable to the release of the /k/ and much shorter than the unaspirated fricatives /ts/, /tʃ/. However, the aspirated and ejective laterals are true fricatives.

While the aspiration of stops is markedly long compared to most other languages, the aspiration of the affricates is quite short: the main feature distinguishing /ts/ and /tʃ/ from /tsʰ/ and /tʃʰ/ is that the frication is half again as long in the latter: [tsˑʰ], [tʃʰˑ]. /tɬʰ/ is similarly long, [tɬˑʰ]. The ejectives /tsʼ/, /tɬʼ/, /tʃʼ/, on the other hand, have short frication, presumably due to the lack of pulmonic airflow

Airstream mechanism

In phonetics, the airstream mechanism is the method by which airflow is created in the vocal tract. Along with phonation, it is one of two mandatory aspects of sound production; without these, there can be no speech sound....

. There is a period of near silence before the glottalized onset of the vowel. In /tɬʼ/ there may be a double glottal release, or a creaky

Creaky voice

In linguistics, creaky voice , is a special kind of phonation in which the arytenoid cartilages in the larynx are drawn together; as a result, the vocal folds are compressed rather tightly, becoming relatively slack and compact...

onset to the vowel not found in the other ejective affricates.

Continuants. Navajo voiceless continuants are realized as fricatives. They are typically noisier than the fricatives that occur in English. The palato-alveolars /ʃ, ʒ/ are not labialized unlike English and other European languages (McDonough 2003: 130).

Navajo also does not have consistent phonetic voicing in the "voiced" continuant members. Although [z, l, ʒ, ɣ] are described as voiced in impressionist descriptions (such as Hoijer 1945a), data from spectrogram

Spectrogram

A spectrogram is a time-varying spectral representation that shows how the spectral density of a signal varies with time. Also known as spectral waterfalls, sonograms, voiceprints, or voicegrams, spectrograms are used to identify phonetic sounds, to analyse the cries of animals; they were also...

s shows that they may be partially devoiced during the constriction. In stem-initial position, /l/ tends to be fully voiced, /ʒ/ has a slight tendency to be voiceless near the offset, /z/ is often mostly voiceless with phonetic voicing only at the onset, /ɣ/ is also only partially voiced with voicing at onset. A more consistent acoustic correlate of the "voicing" is the duration of the consonant: "voiceless" consonants have longer durations than "voiced" consonants. Based on this, McDonough 2003 argues that the distinction is better captured with the notion of a fortis/lenis contrast. A further characteristic of voicing in Navajo is that it is marginally contrastive. (See the voicing assimilation section.)

Navajo lacks a clear distinction between phonetic fricatives and approximants. Although the pair [ɬ] : [l] has been described as a fricative and an approximant, respectively, the lack of a consistent contrast between the two phonetic categories and a similar patterning with other fricative pairs suggests that they are better described as continuants. Additionally, observations have been made about the less fricative-like nature of [ɣ, ɣʷ] and the more fricative-like nature of [j].

Sonorants. A more abstract analysis of Navajo posits two different /j/ phonemes. (See the Velar /ɣ/, palatal /j/ for elaboration.)

The glottalized sonorants are the result of d-effect on the non-glottalized counterparts. (See the d-effect section for further explanation.) A strict structuralist analysis, such as that of Hoijer (1945a) and Sapir & Hoijer (1967), considers them phonemic.

Glottal(ized) consonants. Consonants involving a glottal closure — the glottal stop, ejective stops, and the glottalized sonorants — may have optional creaky voice

Creaky voice

In linguistics, creaky voice , is a special kind of phonation in which the arytenoid cartilages in the larynx are drawn together; as a result, the vocal folds are compressed rather tightly, becoming relatively slack and compact...

on voiced sounds adjacent to the glottal gesture. Glottal stops may also be realized entirely as creaky voice instead of single glottal closure. Ejectives in Navajo differ from the ejectives in many other languages in that the glottal closure is not released near-simultaneously with the release of the oral closure (as is common in other languages) — it is held for a significant amount of time following oral release. The glottalized sonorants /mʼ, nʼ/ are articulated with a glottal stop preceding the oral closure with optional creaky voice during the oral closure: [ʔm ~ ʔm̰, ʔn ~ ʔn̰].

Labialized consonants. Consonants /kʰʷ, xʷ, ɣʷ, hʷ/ are predictable variants that occur before the rounded oral vowel /o/. However, these sounds also occur before the vowels /i, e, a/ where they contrast with their non-labialized counterparts /kʰ, x, ɣ, h/.

Velar /ɣ/, palatal /j/

The phonological contrast between the velar obstruent /ɣ/ and the palatal glide /j/ is neutralized in certain contexts. However, in these contexts, they may often be distinguished from each other by their different phonological patterning.Before the rounded /o/, /ɣ/ is phonetically strongly labialized as [ɣʷ]; elsewhere, it lacks the labialization. As noted above, the lenis continuants like /ɣ/ are often very weak fricatives somewhere between a typical fricative constriction (e.g. [ɣ]) and a more open approximant constriction (e.g. [ɰ]) — this will be symbolized here as [ɰ̝]. Hoijer (1945a) describes the [ɰ̝ʷ] realization as being similar to English [w] but differing in having slight frication at the beginning of the articulation. The realization before /a/ varies between an approximant [ɰ] and a weakly fricated approximant [ɰ̝]. The following verb stem has different velar allophones of the stem-initial consonant:

| Underlying | Phonetic | Orthography | Gloss |

|---|---|---|---|

| /ɣàʃ/ | [ɰ̝àʃ] | "make bubbling noise" (iterative, continuative) | |

| /ɣòʃ/ | [ɰ̝ʷòʃ] | "make bubbling noise" (iterative, repetitive) |

The palatal glide /j/ is also phonetically between an approximant [j] and a fricative [ʝ]. Hoijer (1945a) compares it to English [j] with a "slight but audible 'rubbiness' or frication".

The contrast between velar /ɣ/ and palatal /j/ is found before both back vowels /a, o/ as the following contrasts demonstrate:

| Underlying | Phonetic | Orthography | Gloss | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| contrast before /a/ | /pìɣàːʔ/ | [pɪ̀ɰ̝àːʔ] | "its fur, wool" | |

| /pìjàːʔ/ | [pɪ̀j˔àːʔ] | "its lice" | ||

| contrast before /o/ | /pìɣòl/ | [pɪ̀ɰ̝ʷòl] | "its marrow" | |

| /pìjòl/ | [pɪ̀j˔òl] | "its breath" | ||

Before the front vowels /i, e/, however, the contrast between /ɣ/ and /j/ is neutralized to a palatal articulation much like the weakly fricative [j˔] realization of /j/ that occurs before back vowels. However, the underlying consonant can be ascertained in verb stems and noun stems via their different realizations in a voiceless (i.e. fortis) context. The underlying velar surfaces as a voiceless palatal fricative [ç] in these environments:

| Fortis context | Lenis context | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phonetic | Orthographic | Gloss | Phonetic | Orthographic | Gloss | |

| [çéːɬ] | "bundle" | [pɪ̀j˔éːl] | "her bundle" | |||

| [j˔ɪ̀ʃçɪ̀ʒ] | "I pick (corn)" | [j˔ɪ̀j˔ɪ̀ʒ] | "she picks (corn)" | |||

The stem-initial velar of the noun stem /xéːɬ/ has a voiceless fortis realization of [ç] (as [çéːɬ]) when word-initial. When intervocalic, it is realized as lenis [j˔] (as [-j˔éːl]). Likewise, the underlying velar of the verb stem /xɪ̀ʒ/ is a voiceless [ç] after the preceding voiceless [ʃ] and lenis [j˔] when intervocalic. Thus, the alternation of [ç ~ j˔] in the two contexts is indicative of an underlying velar consonant. Similarly before the back vowels, the velar continuant has the alternations [x ~ ɰ̝] and [xʷ ~ ɰ̝ʷ] as shown in the examples below:

| Fortis context | Lenis context | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phonetic | Orthographic | Gloss | Phonetic | Orthographic | Gloss | |

| before /a/ | [hànɪ́ɬxáːʃ] | "you make it boil" | [hànɪ́lɰ̝áːʃ] | "it comes to a boil" | ||

| before /o/ | [ʔàɬxʷòʃ] | "he's sleeping" | [ʔáhòtɪ̀lɰ̝ʷòʃ] | "he's pretending to be asleep" | ||

An underlying palatal /j/ can determined by alternations which differ from the velar alternations. However, /j/ has two different alternation patterns which have led to the positing of two distinct phonemes. Incidentally, the two different phonemes are also connected to two different reconstructed consonants in Proto-Athabascan. One of these /j/ phonemes is considered an obstruent as it has a fricative realization of [s] in fortis contexts. It is often symbolized as a palatalized (or front velar) fricative (in Americanist

Americanist

Americanist may refer to:* a scholar specializing in American studies* Americanist phonetic notation* International Congress of Americanists* Society of Early Americanists...

phonetic notation) and is a reflex of Proto-Athabascan . It may be considered coronal because of its coronal voiceless allophone.

| Fortis context | Lenis context | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phonetic | Orthographic | Gloss | Phonetic | Orthographic | Gloss | |

| before /i/ | [sɪ̀n] | "song" | [pɪ̀j˔ìːn] | "her song" | ||

| before /a/ | [hònɪ̀sːã́] | "I'm wise" | [hój˔ã́] | "she's wise" | ||

| before /o/ | [hànɪ̀sːóːt] | "I drive them out" | [hàɪ̀nɪ̀j˔óːt] | "she drives them out" | ||

In the above examples, the fortis realization is [s] in the stems [sɪ̀n], [-sã́], [-sóːt] while the lenis realization is the glide [j˔] in the corresponding [-j˔ɪ̀n], [-j˔ã́], [-j˔óːt].

The other underlying (or morphophonemic) palatal /j/ is considered a sonorant and has an invariant [j˔] realization in both fortis (voiceless) and lenis (voiced) contexts. This phoneme is relatively rare, occurring in only a few morpheme

Morpheme

In linguistics, a morpheme is the smallest semantically meaningful unit in a language. The field of study dedicated to morphemes is called morphology. A morpheme is not identical to a word, and the principal difference between the two is that a morpheme may or may not stand alone, whereas a word,...

s. It is a reflex of Proto-Athabascan (as symbolized in Americanist notation). Two examples are below:

| Fortis context | Lenis context | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phonetic | Orthographic | Gloss | Phonetic | Orthographic | Gloss | |

| before /a/ | [j˔àːʔ] | "louse" | [ʃɪ̀j˔àʔ] | "my louse" | ||

| before /o/ | [hònɪ̀ʃj˔óɪ́] | "I'm energetic" | [hònɪ́j˔óɪ́] | "you're energetic" | ||

A further distinction between the different phonemes are found in the context of d-effect (for which, see the d-effect section).

The varying contextual realizations of these three underlying segments are summarized in the following table:

| Underlying segment | Lenis | Fortis | D-effect | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| before /a/ | before /o/ | before /i, e/ | |||

| /ɣ/ | ɰ̝ | ɰ̝ʷ | j˔ | x | k |

| /j/ < Proto-Ath. |

j˔ | j˔ | j˔ | s | ts |

| /j/ < Proto-Ath. |

j˔ | j˔ | j˔ | j˔ | jˀ˔ |

Voicing assimilation

The voiced continuants [z, l, ʒ, ɰ̝] at the beginning of stems vary with their voiceless counterparts [s, ɬ, ʃ, x], respectively. The voiceless variants occur when preceded by voiceless consonants, such as [s, ɬ, ʃ, h] while the voiced variants occur between voiced sounds (typically intervocalically). For example, the verb stems meaning "spit it out", "be burning", "spit", and "be ticklish" have the following forms with alternating voiced and voiceless stem-initial consonants:| Phonetic forms | Orthographic forms | English gloss |

|---|---|---|

| [zóːh ~ sóːh] | ~ | "spit it out" |

| [lɪ̀t ~ ɬɪ̀t] | ~ | "be burning" |

| [ʒàh ~ ʃàh] | ~ | "spit" |

| [ɰ̝ʷòʒ ~ xʷòʒ] | ~ | "be ticklish" |

Since the voicing is predictable, it can be represented more abstractly as an underlying

Underlying representation

In some models of phonology as well as morphophonology, the underlying representation or underlying form of a word or morpheme is the abstract form the word or morpheme is postulated to have before any phonological rules have applied to it. If more rules apply to the same form, they can apply...

consonant that is underspecified with respect to voicing. These archiphonemes can be indicated with the capital letters /Z, L, Ʒ, Ɣ/. The variant voicing of the stem-initial consonant can be found in the context of subject person prefixes which are added to the verb stem:

| Phonetic form | Orthographic form | Underlying segments | English gloss |

|---|---|---|---|

| [hàɪ̀tɪ̀zóːh] | hàìtì-∅-Zóːh | "he spits it out" | |

| [hàtɪ̀sóːh] | hàtì-ʃ-Zóːh | "I spit it out" | |

| [hàtòhsóːh] | hàtì-oh-Zóːh | "you two spit it out" | |

| [tɪ̀lɪ̀t] | tì-∅-Lìt | "he's burning" | |

| [tɪ̀ʃɬɪ̀t] | tì-ʃ-Lìt | "I'm burning" | |

| [tòhɬɪ̀t] | tì-oh-Lìt | "you two are burning" | |

| [tɪ̀ʒàh] | tì-∅-Ʒàh | "he spits" | |

| [tɪ̀ʃàh] | tì-ʃ-Ʒàh | "I spit" | |

| [tòhʃàh] | tì-oh-Ʒàh | "you two spit" | |

| [jɪ̀ɰ̝ʷòʒ] | ∅-Ɣòʒ | "he's ticklish" | |

| [jɪ̀ʃxʷòʒ] | ∅-ʃ-Ɣòʒ | "I'm ticklish" | |

| [wòhxʷòʒ] | ∅-oh-Ɣòʒ | "you two are ticklish" | |

As the above examples show, the stem-initial consonant is voiced when intervocalic and voiceless when it is preceded by a voiceless /ʃ-/ first person singular subject prefix or a voiceless [h] in the /oh-/ two person dual subject prefix.

Another example of contextual voicing of verb-stem-initial consonants occurs when a voiceless /-ɬ-/ classifier prefix occurs before the stem as in the following:

| Phonetic form | Orthographic form | Underlying segments | English gloss |

|---|---|---|---|

| [tìːlzáːs] | tì-Vt-ɬ-Záːs | "we two dribble it along" | |

| [jɪ̀tɪ̀sáːs] | jìtì-ɬ-Záːs | "he dribbles it along" | |

| [tɪ̀sáːs] | tì-ʃ-ɬ-Záːs | "I dribble it along" | |

| [tòhsáːs] | tì-oh-ɬ-Záːs | "you two dribble it long" |

In the verb-form [tìːlzáːs] "we two dribble it along", the /Z/ occurs between a voiced [l] and the voiced stem vowel [áː]. Thus it is realized as a voiced [z]. Here the /-ɬ-/ classifier is voiced due to the d-effect of the preceding /Vt-/ first person dual subject prefix. (See the section on Navajo d-effect for further explanation.) In the other verb-forms, the stem-initial /Z/ is preceded by voiceless /-ɬ-/ classifier which results in a voiceless realization of [s]. In the surface verb-forms, the underlying /-ɬ-/ classifier is not pronounced due to a phonotactic restriction on consonant clusters.

The initial consonant of noun stems also display contextual voicing:

| Phonetic form | Orthographic form | Underlying segments | English gloss |

|---|---|---|---|

| [sàːt] | sàːt | "language" | |

| [pɪ̀zàːt] | pì-sàːt | "his language" | |

| [ɬɪ̀t] | ɬìt | "smoke" | |

| [pɪ̀lɪ̀t] | pì-ɬìt | "his smoke" | |

| [ʃàːʒ] | ʃàːʒ | "callous" | |

| [pɪ̀ʒàːʒ] | pì-ʃàːʒ | "his callous" | |

| [xʷòʃ] | xòʃ | "cactus" | |

| [pɪ̀ɰ̝ʷòʃ] | pì-xòʃ | "his cactus" | |

Here an intervocalic context is created by inflecting the nouns , , , with a [pɪ̀-] third person prefix which ends in a vowel. In this context, the stem-initial consonant is voiced. When these nouns lack a prefix (in which case the stem-initial consonant is word-initial), the realization is voiceless.

However, in some noun stems, the stem-initial continuant does not voice when intervocalic: [ʔàʃĩ̀ːh] "salt".

Dorsal place assimilation

The dorsal consonantDorsal consonant

Dorsal consonants are articulated with the mid body of the tongue . They contrast with coronal consonants articulated with the flexible front of the tongue, and radical consonants articulated with the root of the tongue.-Function:...

s /k, kʰ, kʼ, x, ɣ/ (orthographic , , , , ) have contextual phonetic variants (i.e. allophone

Allophone

In phonology, an allophone is one of a set of multiple possible spoken sounds used to pronounce a single phoneme. For example, and are allophones for the phoneme in the English language...

s) varying along place of articulation

Place of articulation

In articulatory phonetics, the place of articulation of a consonant is the point of contact where an obstruction occurs in the vocal tract between an articulatory gesture, an active articulator , and a passive location...

that depend on the following vowel environment. They are realized as palatals before the front vowels and and as velars before the back vowels and . Additionally, they are labialized before the rounded back vowel o. This likewise happens with the velar frication of the aspirated /tʰ/.

| Underlying consonant | Phonetic realizations | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Palatal | Velar | Labial | |

| k | [c(ʝ)] | [k(ɣ)] | [k(ɣ)ʷ] |

| kʰ | [cç] | [kx] | [kxʷ] |

| kʼ | [cʼ] | [kʼ] | [kʼʷ] |

| x | [ç] | [x] | [xʷ] |

| ɣ | [j˔] | [ɰ̝] | [ɰ̝ʷ] |

| tʰ | [tç] | [tx] | [txʷ] |

Coronal harmony

Navajo has coronalCoronal consonant

Coronal consonants are consonants articulated with the flexible front part of the tongue. Only the coronal consonants can be divided into apical , laminal , domed , or subapical , as well as a few rarer orientations, because only the front of the tongue has such...

sibilant consonant harmony

Consonant harmony

Consonant harmony is a type of "long-distance" phonological assimilation akin to the similar assimilatory process involving vowels, i.e. vowel harmony.-Examples:...

. Alveolar sibilants in prefixes assimilate

Assimilation (linguistics)

Assimilation is a common phonological process by which the sound of the ending of one word blends into the sound of the beginning of the following word. This occurs when the parts of the mouth and vocal cords start to form the beginning sounds of the next word before the last sound has been...

to post-alveolar sibilants in stems, and post-alveolar prefixal sibilants assimilate to alveolar stem sibilants. For example, the si- stative perfective is realized as si- or shi- depending upon whether the stem contains a post-alveolar sibilant:

| shibeezh | "it is boiled" (perfective) | s > sh, triggered by the stem-final zh |

| sido | "it is hot" (perfective) |

D-effect

A particular type of morphophonemic alternationApophony

In linguistics, apophony is the alternation of sounds within a word that indicates grammatical information .-Description:Apophony is...

(or mutation

Consonant mutation

Consonant mutation is when a consonant in a word changes according to its morphological and/or syntactic environment.Mutation phenomena occur in languages around the world. A prototypical example of consonant mutation is the initial consonant mutation of all modern Celtic languages...

) occurring in Athabascan languages called d-effect is found in Navajo. The alternation in most cases is a fortition

Fortition

Fortition is a consonantal change from a 'weak' sound to a 'strong' one, the opposite of the more common lenition. For example, a fricative or an approximant may become a plosive...

(or strengthening) process. The initial consonant of a verb stem alternates with a strengthened consonant when it is preceded by a /-t-/ (orthographic ) "classifier" prefix or the /-Vt-/ first person dual subject prefix. The underlying /t/ of these prefixes is absorbed into the following stem. D-effect can be viewed prosodically as the result of a phonotactic constraint on consonant clusters that would otherwise result from the concatenation of underlying segments (McDonough 2003: 60). There is thus an interaction between a requirement for the grammatical information to be expressed in the surface form and an avoidance of having sequences of consonants. (See the syllable section for more on phonotactics.)

The fortition is typically a change from continuant to affricate or continuant to stop (i.e. adding a period of closure to the articulation). However, other changes involve glottalization of the initial consonant:

| Prefix consonant + Stem-initial consonant | Surface consonant | Example | |

|---|---|---|---|

| t- + -Z | > | -ts | tʃʼéná-t-Zìt > tʃʼéná-tsìt () "he woke up" |

| t- + -L | > | -tl | ʔánéìnì-t-Laː > ʔánéìnì-tlaː () "you repaired it" |

| t- + -Ʒ | > | -tʃ | ʔákʼídíní-t-Ʒéːʔ > ʔákʼídíní-tʃéːʔ () "you spit on yourself" |

| t- + -j | > | -ts | nìː-Vt-jòɬ > nìː-tsòɬ () "we two are driving them along" (cf. jìnòː-jòɬ () "he's driving them along") |

| t- + -Ɣ | > | -k | jì-Vt-Ɣòʒ > jìː-kòʒ () "we two are ticklish" (cf. jì-ɣòʒ () "he's ticklish") |

| t- + -ʔ | > | -tʼ | nànìʃ-t-ʔìn > nànìʃ-tʼìn () "I'm hidden" |

| t- + -m | > | -mʼ | jì-Vt-màs > jìː-mʼàs () "we two are rolling along" (cf. jì-màs () "he's rolling along") |

| t- + -n | > | -nʼ | náːtòː-t-nìːt > náːtòː-nʼìːt () "she said again" |

| t- + -j | > | -jʼ | xònì-Vt-jóí > xònìː-jʼóí () "we two are energetic" (cf. xònìʃ-jʼóí () "I'm energetic") |

The two occurrences of t- + -j in the chart above reflect two different patterns of d-effect involving stem-initial /j/. Often different underlying consonants are posited to explain the different alternation. The first alternation is posited as a result of underlying t- + -ɣ leading to a d-effect mutation of /dz/. The other is t- + -j resulting in /jˀ/. (See the velar /ɣ/, palatal /j/ section for further explanation.)

Another example of d-effect influences not the stem-initial consonant but the classifier prefix. When the /-Vt-/ first person dual subject prefix precedes the /-ɬ-/ (orthographic ) classifier prefix, the /-ɬ-/ classifier is realized as voiced [l]:

| Prefix consonant + Classifier consonant | Surface consonant | Example | |

|---|---|---|---|

| t- + -ɬ- | > | -l- | jì-Vt-ɬ-Ʒõ̀ːh > jìː-l-ʒõ̀ːh () "we two tame it" |

Vowels

Navajo has four contrastive vowelVowel

In phonetics, a vowel is a sound in spoken language, such as English ah! or oh! , pronounced with an open vocal tract so that there is no build-up of air pressure at any point above the glottis. This contrasts with consonants, such as English sh! , where there is a constriction or closure at some...

qualities [i, e, o, ɑ] at three different vowel heights (high, mid, low) and a front-back contrast between the mid vowels [e, o]. There are also two contrastive vowel length

Vowel length

In linguistics, vowel length is the perceived duration of a vowel sound. Often the chroneme, or the "longness", acts like a consonant, and may etymologically be one, such as in Australian English. While not distinctive in most dialects of English, vowel length is an important phonemic factor in...

s and a contrast in nasalization

Nasalization

In phonetics, nasalization is the production of a sound while the velum is lowered, so that some air escapes through the nose during the production of the sound by the mouth...

. This results in 16 phonemic vowels, shown below.

| Front Front vowel A front vowel is a type of vowel sound used in some spoken languages. The defining characteristic of a front vowel is that the tongue is positioned as far in front as possible in the mouth without creating a constriction that would be classified as a consonant. Front vowels are sometimes also... |

Back Back vowel A back vowel is a type of vowel sound used in spoken languages. The defining characteristic of a back vowel is that the tongue is positioned as far back as possible in the mouth without creating a constriction that would be classified as a consonant. Back vowels are sometimes also called dark... |

|

|---|---|---|

| High Close vowel A close vowel is a type of vowel sound used in many spoken languages. The defining characteristic of a close vowel is that the tongue is positioned as close as possible to the roof of the mouth without creating a constriction that would be classified as a consonant.This term is prescribed by the... |

iː | |

| Mid Open-mid vowel An open-mid vowel is a type of vowel sound used in some spoken languages. The defining characteristic of an open-mid vowel is that the tongue is positioned two-thirds of the way from an open vowel to a mid vowel... |

eː | oː |

| Low Open vowel An open vowel is defined as a vowel sound in which the tongue is positioned as far as possible from the roof of the mouth. Open vowels are sometimes also called low vowels in reference to the low position of the tongue... |

ɑː |

| Front Front vowel A front vowel is a type of vowel sound used in some spoken languages. The defining characteristic of a front vowel is that the tongue is positioned as far in front as possible in the mouth without creating a constriction that would be classified as a consonant. Front vowels are sometimes also... |

Back Back vowel A back vowel is a type of vowel sound used in spoken languages. The defining characteristic of a back vowel is that the tongue is positioned as far back as possible in the mouth without creating a constriction that would be classified as a consonant. Back vowels are sometimes also called dark... |

|

|---|---|---|

| High Close vowel A close vowel is a type of vowel sound used in many spoken languages. The defining characteristic of a close vowel is that the tongue is positioned as close as possible to the roof of the mouth without creating a constriction that would be classified as a consonant.This term is prescribed by the... |

ɪ | |

| Mid Open-mid vowel An open-mid vowel is a type of vowel sound used in some spoken languages. The defining characteristic of an open-mid vowel is that the tongue is positioned two-thirds of the way from an open vowel to a mid vowel... |

e | o |

| Low Open vowel An open vowel is defined as a vowel sound in which the tongue is positioned as far as possible from the roof of the mouth. Open vowels are sometimes also called low vowels in reference to the low position of the tongue... |

ɑ |

| Front Front vowel A front vowel is a type of vowel sound used in some spoken languages. The defining characteristic of a front vowel is that the tongue is positioned as far in front as possible in the mouth without creating a constriction that would be classified as a consonant. Front vowels are sometimes also... |

Back Back vowel A back vowel is a type of vowel sound used in spoken languages. The defining characteristic of a back vowel is that the tongue is positioned as far back as possible in the mouth without creating a constriction that would be classified as a consonant. Back vowels are sometimes also called dark... |

|

|---|---|---|

| High Close vowel A close vowel is a type of vowel sound used in many spoken languages. The defining characteristic of a close vowel is that the tongue is positioned as close as possible to the roof of the mouth without creating a constriction that would be classified as a consonant.This term is prescribed by the... |

ĩː | |

| Mid Open-mid vowel An open-mid vowel is a type of vowel sound used in some spoken languages. The defining characteristic of an open-mid vowel is that the tongue is positioned two-thirds of the way from an open vowel to a mid vowel... |

ẽː | õː |

| Low Open vowel An open vowel is defined as a vowel sound in which the tongue is positioned as far as possible from the roof of the mouth. Open vowels are sometimes also called low vowels in reference to the low position of the tongue... |

ɑ̃ː |

| Front Front vowel A front vowel is a type of vowel sound used in some spoken languages. The defining characteristic of a front vowel is that the tongue is positioned as far in front as possible in the mouth without creating a constriction that would be classified as a consonant. Front vowels are sometimes also... |

Back Back vowel A back vowel is a type of vowel sound used in spoken languages. The defining characteristic of a back vowel is that the tongue is positioned as far back as possible in the mouth without creating a constriction that would be classified as a consonant. Back vowels are sometimes also called dark... |

|

|---|---|---|

| High Close vowel A close vowel is a type of vowel sound used in many spoken languages. The defining characteristic of a close vowel is that the tongue is positioned as close as possible to the roof of the mouth without creating a constriction that would be classified as a consonant.This term is prescribed by the... |

ĩ | |

| Mid Open-mid vowel An open-mid vowel is a type of vowel sound used in some spoken languages. The defining characteristic of an open-mid vowel is that the tongue is positioned two-thirds of the way from an open vowel to a mid vowel... |

ẽ | õ |

| Low Open vowel An open vowel is defined as a vowel sound in which the tongue is positioned as far as possible from the roof of the mouth. Open vowels are sometimes also called low vowels in reference to the low position of the tongue... |

ɑ̃ |

There is a phonetic vowel quality difference between the long high vowel /iː/ (orthographic ) and the short high vowel /i/ (orthographic ): the shorter vowel is significantly lower at [ɪ] than its long counterpart. This phonetic difference is salient to native speakers, who will consider a short vowel at a higher position to be a mispronunciation. Similarly, short /e/ is pronounced [ɛ]. Short /o/ is a bit more variable and more centralized, covering the space [ɔ] ~ [ɞ]. Notably, the variation in /o/ does not approach [u], which is a true gap in the vowel space.

Although the nasalization is contrastive in the surface phonology, many instances of nasalized vowels can be derived from a sequence of Vowel + Nasal consonant in a more abstract analysis. Additionally, there are alternations between long and short vowels that are predictable.

There have been a number of somewhat different descriptions of Navajo vowels, which are conveniently summarized in McDonough (2003).

Acoustic phonetics

Formant

Formants are defined by Gunnar Fant as 'the spectral peaks of the sound spectrum |P|' of the voice. In speech science and phonetics, formant is also used to mean an acoustic resonance of the human vocal tract...

s of Navajo long and short vowel pairs as pronounced by 10 female and 4 male native speakers. Below are the median

Median

In probability theory and statistics, a median is described as the numerical value separating the higher half of a sample, a population, or a probability distribution, from the lower half. The median of a finite list of numbers can be found by arranging all the observations from lowest value to...

values of the first (F1) and second (F2) formants for this study.

| Vowel | F1 | F2 | Vowel | F1 | F2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| iː | 372 | 2532 | oː | 513 | 957 |

| i | 463 | 2057 | o | 537 | 1154 |

| eː | 487 | 2195 | aː | 752 | 1309 |

| e | 633 | 1882 | a | 696 | 1454 |

An earlier study (McDonough et al. 1993) has measurements from 7 females:

| Vowel | F1 | F2 | Vowel | F1 | F2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| iː | 315 | 2528 | oː | 488 | 943 |

| i | 391 | 2069 | o | 558 | 1176 |

| eː | 498 | 2200 | aː | 802 | 1279 |

| e | 619 | 2017 | a | 808 | 1299 |

Tones

Navajo has two toneTone (linguistics)

Tone is the use of pitch in language to distinguish lexical or grammatical meaning—that is, to distinguish or inflect words. All verbal languages use pitch to express emotional and other paralinguistic information, and to convey emphasis, contrast, and other such features in what is called...

s: high and low. Orthographically, high tone is marked with an acute accent

Acute accent

The acute accent is a diacritic used in many modern written languages with alphabets based on the Latin, Cyrillic, and Greek scripts.-Apex:An early precursor of the acute accent was the apex, used in Latin inscriptions to mark long vowels.-Greek:...

(á) over the affected vowel, while low tone is left unmarked (a). This reflects the tonal polarity of Navajo, as syllables have low tone by default.

Long vowels normally have level tones (áá, aa). However, in grammatical contractions

Contraction (grammar)

A contraction is a shortened version of the written and spoken forms of a word, syllable, or word group, created by omission of internal letters....

and in Spanish loan words such as "money" (from Spanish ), long vowels may have falling (áa) or rising (aá) tones.

The sonorant n also carries tone when it is syllabic. Here again, the high tone is marked with an acute (ń) while the low tone is left unmarked (n).

Despite the fact that low tone is the default, these syllables are not underspecified for tone: they have a distinct phonetic tone, and their pitch is not merely a function of their environment. This contrasts with the related Carrier language

Carrier language

The Carrier language is a Northern Athabaskan language. It is named after the Dakelh people, a First Nations people of the Central Interior of British Columbia, Canada, for whom Carrier is the usual English name. People who are referred to as Carrier speak two related languages. One,...

. As in many languages, however, the pitches at the beginnings of Navajo vowels are lower after voiced consonants than after tenuis and aspirated consonants. After ejective consonants, only high tones are lowered, so that the distinction between high and low tone is reduced. However, the type of consonant has little effect on the pitch in the middle of the vowel, so that vowels have characteristic rising pitches after voiced consonants.

The pitch of a vowel is also affected by the tone of the previous syllable: in most cases, this is has as great an effect on the pitch of a syllable as its own tone. However, this effect is effectively blocked by an intervening aspirated consonant. (deJong & McDonough 1993)

Tonological processes

Navajo nouns are simple: /kʰǫ́/ [kʰǫ́] kǫ́ "fire", /pi-tiɬ/ [pìtìɬ] bidił "his blood". Most long nouns are actually deverbal.In verbs, with few exceptions, only stems

Word stem

In linguistics, a stem is a part of a word. The term is used with slightly different meanings.In one usage, a stem is a form to which affixes can be attached. Thus, in this usage, the English word friendships contains the stem friend, to which the derivational suffix -ship is attached to form a new...

may carry a high tone: onsonant. Prefixes are mostly single consonants, C-, and do not carry tone. The one exception is the high-tone vocalic prefix /ʌ́n/-. Most other tone-bearing units in the Navajo verb are second stems or clitic

Clitic

In morphology and syntax, a clitic is a morpheme that is grammatically independent, but phonologically dependent on another word or phrase. It is pronounced like an affix, but works at the phrase level...

s.

All Navajo verbs can be analyzed as compounds, and this greatly simplifies the description of tone. There are two obligatory components, the "I" stem (for "inflection") and the "V" stem (for "verb"), each potentially bearing a high tone, and each preceded by its own prefixes. In addition, the compound as a whole takes 'agreement' prefixes like the prefixes found on nouns. This entire word may then take proclitics, which may also carry tone:

| clitics= | agreement– | (prefixes– | I-stem) | + | (prefixes– | V-stem) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tone | tone | tone | ||||

(Hyphens – mark prefixes, double hyphens = mark clitics, and plus signs + join compounds.)

Any high tones on clitics and the prefix /ʌ́n/- spread to the next syllable of the word. This spreading is blocked by long vowels, as can be seen with the iterative clitic /ná/꞊. Compare

/ha꞊niʃ+ɬ-tʃʰaːt/ - [haniʃɬtʃʰaːt]

- hanishchaad

and

/ha꞊ná꞊niʃ+ɬ-tʃʰaːt/ - [hanáníʃɬtʃʰaːt]

- hanáníshchaad,

where the clitic ná= creates a high tone on the following syllable, but,

/ná꞊iːt+l-zéːh/ - [náiːtlzéːh]

- náiilzééh

where it does not.

- conjunct prefixes in verb stems are unmarked for tone (with a few exceptions) — they assimilate to the tones of neighboring prefixes

- tones in disjunct prefixes and stems are underlying specified

- certain enclitics (like the subordinator ) affect the tones of preceding verb stems

Syllable

Stems. The stems (e.g. noun stems, verb stems, etc.) have the following syllableSyllable

A syllable is a unit of organization for a sequence of speech sounds. For example, the word water is composed of two syllables: wa and ter. A syllable is typically made up of a syllable nucleus with optional initial and final margins .Syllables are often considered the phonological "building...

types:

- onsonant

That is, all syllables must have a consonant onset C, a vowel nucleus V. The syllable may carry a high tone T, the vowel nucleus may be short or long, and there may optionally be a consonant coda

Syllable coda

In phonology, a syllable coda comprises the consonant sounds of a syllable that follow the nucleus, which is usually a vowel. The combination of a nucleus and a coda is called a rime. Some syllables consist only of a nucleus with no coda...

.

Prefixes. Prefixes typically have a syllable structure of CV-, such as chʼí- "out horizontally". Exceptions to this are certain verbal prefixes, such as the classifiers (-ł-, -l-, -d-) that occur directly before the verb stem, which consist of a single consonant -C-. A few other verbal prefixes, such as naa- "around, about" on the outer left edge of the verb have long vowels, CVV-. A few prefixes have more complex syllable shapes, such as hashtʼe- "ready, prepared" (CVCCV-). Prefixes do not carry tone.

In some analyses, such as that of Harry Hoijer

Harry Hoijer

Harry Hoijer was a linguist and anthropologist who worked on primarily Athabaskan languages and culture.He additionally documented the Tonkawa language, which is now extinct...

, consider conjunct verbal prefixes to have the syllable shape CV-. In other generative analyses (e.g. McDonough 2003), the same prefixes are considered to have only underlying consonants of the shape C-. Then, in certain environments, an epenthetic vowel (the default vowel is i) is inserted after the consonantal prefix.

Peg elements, segment insertion

All verbs must be disyllabic. Some verbs may only have a single overt nonsyllabic consonantal prefix or a prefix lacking an onset, or no prefix at all before the verb stem. Since all verbs are required to have two syllables, a meaningless prefix must be added to the verb to fulfill the disyllabic requirement. This prosodic prefix is known as a peg element in Athabascan terminology (Edward SapirEdward Sapir

Edward Sapir was an American anthropologist-linguist, widely considered to be one of the most important figures in the early development of the discipline of linguistics....

used the term pepet vowel). For example, the verb meaning "she/he/they is/are crying" has the following morphological composition: Ø-Ø-cha where both the imperfective modal prefix and the third person subject prefix are phonologically null morpheme

Null morpheme

In morpheme-based morphology, a null morpheme is a morpheme that is realized by a phonologically null affix . In simpler terms, a null morpheme is an "invisible" affix. It is also called a zero morpheme; the process of adding a null morpheme is called null affixation, null derivation or zero...

s and the verb stem is -cha. In order for this verb to be complete a yi- peg element must be prefixed to the verb stem, resulting in the verb form yicha. Another examples are verb yishcha "I'm crying" which is morphologically Ø-sh-cha (Ø- null imperfective modal, -sh- first person singular subject, -cha verb stem) and wohcha "you (2+) are crying" which is Ø-oh-cha (Ø- null imperfective modal, -oh- second person dual-plural subject, -cha verb stem). The glide

Semivowel

In phonetics and phonology, a semivowel is a sound, such as English or , that is phonetically similar to a vowel sound but functions as the syllable boundary rather than as the nucleus of a syllable.-Classification:...

consonant of the peg element is y before i, w before o, and gh before a.