Katherine Routledge

Encyclopedia

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

archaeologist who initiated (but did not complete) the first true survey of Easter Island

Easter Island

Easter Island is a Polynesian island in the southeastern Pacific Ocean, at the southeasternmost point of the Polynesian triangle. A special territory of Chile that was annexed in 1888, Easter Island is famous for its 887 extant monumental statues, called moai, created by the early Rapanui people...

.

She was the second child of Kate and Gurney Pease

Pease family (Darlington)

The Pease family was a prominent English and mostly Quaker family associated with Darlington and County Durham and descended from Joseph Pease of Darlington, son of Edward Pease . They were 'one of the great Quaker industrialist families of the nineteenth century, who played a leading role in...

, and was born into a wealthy Quaker family in Darlington

Darlington

Darlington is a market town in the Borough of Darlington, part of the ceremonial county of County Durham, England. It lies on the small River Skerne, a tributary of the River Tees, not far from the main river. It is the main population centre in the borough, with a population of 97,838 as of 2001...

, northern England. She graduated from Somerville Hall (now Somerville College, Oxford

Somerville College, Oxford

Somerville College is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England, and was one of the first women's colleges to be founded there...

), with Honours in Modern History in 1895, and for a while taught courses through the Extension Division and at Darlington Training College. After the Second Boer War

Second Boer War

The Second Boer War was fought from 11 October 1899 until 31 May 1902 between the British Empire and the Afrikaans-speaking Dutch settlers of two independent Boer republics, the South African Republic and the Orange Free State...

, she traveled to South Africa

South Africa

The Republic of South Africa is a country in southern Africa. Located at the southern tip of Africa, it is divided into nine provinces, with of coastline on the Atlantic and Indian oceans...

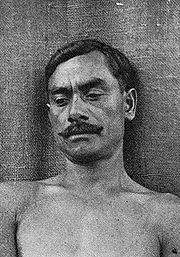

with a committee to investigate the resettlement of single working women from England to South Africa. In 1906 she married William Scoresby Routledge

William Scoresby Routledge

William Scoresby Routledge was a British ethnographer, anthropologist and adventurer. With his wife, Katherine Routledge, he completed the first ethnographies of the Kikuyu and the people of Rapa Nui .-Early life:...

. The couple went to live among the Kikuyu people of what was then British East Africa, and in 1910 jointly published a book of their research entitled With A Prehistoric People.

Easter Island

Easter Island

Easter Island is a Polynesian island in the southeastern Pacific Ocean, at the southeasternmost point of the Polynesian triangle. A special territory of Chile that was annexed in 1888, Easter Island is famous for its 887 extant monumental statues, called moai, created by the early Rapanui people...

/Rapa Nui. They had a state-of-the-art 90 feet (27.4 m) long Schooner

Schooner

A schooner is a type of sailing vessel characterized by the use of fore-and-aft sails on two or more masts with the forward mast being no taller than the rear masts....

built and named it Mana

Mana

Mana is an indigenous Pacific islander concept of an impersonal force or quality that resides in people, animals, and inanimate objects. The word is a cognate in many Oceanic languages, including Melanesian, Polynesian, and Micronesian....

. They affiliated with the British Association for the Advancement of Science

British Association for the Advancement of Science

frame|right|"The BA" logoThe British Association for the Advancement of Science or the British Science Association, formerly known as the BA, is a learned society with the object of promoting science, directing general attention to scientific matters, and facilitating interaction between...

, the British Museum

British Museum

The British Museum is a museum of human history and culture in London. Its collections, which number more than seven million objects, are amongst the largest and most comprehensive in the world and originate from all continents, illustrating and documenting the story of human culture from its...

and the Royal Geographical Society

Royal Geographical Society

The Royal Geographical Society is a British learned society founded in 1830 for the advancement of geographical sciences...

, recruited a crew and borrowed an officer from the Royal Navy

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Founded in the 16th century, it is the oldest service branch and is known as the Senior Service...

. The Mana departed Falmouth

Falmouth, Cornwall

Falmouth is a town, civil parish and port on the River Fal on the south coast of Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. It has a total resident population of 21,635.Falmouth is the terminus of the A39, which begins some 200 miles away in Bath, Somerset....

on 25 March 1913.

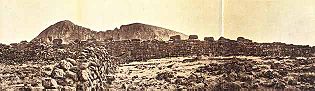

They arrived on Easter Island on 29 March 1914. They established two base camps, one in the area of Mataveri and the other at the statue quarry, Rano Raraku

Rano Raraku

Rano Raraku is a volcanic crater formed of consolidated volcanic ash, or tuff, and located on the lower slopes of Terevaka in the Rapa Nui National Park on Easter Island. It was a quarry for about 500 years until the early eighteenth century, and supplied the stone from which about 95% of the...

and also explored Orongo

Orongo

‘Orongo is a stone village and ceremonial centre at the southwestern tip of Rapa Nui . The first half of the ceremonial village's 53 stone masonry houses were investigated and restored in 1974 by American archaeologist William Mulloy...

and Anakena

Anakena

Anakena is a white coral sand beach in Rapa Nui National Park on Rapa Nui , a Chilean island in the Pacific Ocean. Anakena has two ahus, one with a single moai and the other with six...

. With the help of a talented islander known as Juan Tepano, Routledge proceeded to interview the natives and catalogue the Moai

Moai

Moai , or mo‘ai, are monolithic human figures carved from rock on the Chilean Polynesian island of Easter Island between the years 1250 and 1500. Nearly half are still at Rano Raraku, the main moai quarry, but hundreds were transported from there and set on stone platforms called ahu around the...

(giant statues) and the Ahus they had once stood on. They excavated over 30 Moai, visited the tribal elders in their leper colony

Leper colony

A leper colony, leprosarium, or lazar house is a place to quarantine leprous people.-History:Leper colonies or houses became widespread in the Middle Ages, particularly in Europe and India, and often run by monastic orders...

north of Hanga Roa

Hanga Roa

Hanga Roa is the main town, harbour and capital of the Chilean province of Easter Island. It is located in the southern part of the island's west coast, in the lowlands between the extinct volcanoes of Terevaka and Rano Kau....

and recorded various legends and oral histories including that of Hotu Matua, the Birdman

Tangata manu

The Tangata manu , was the winner of a traditional competition on Rapa Nui . The ritual was an annual competition to collect the first Sooty Tern egg of the season from the islet of Motu Nui, swim back to Rapa Nui and climb the sea cliff of Rano Kau to the clifftop village of Orongo.-Myth:In the...

cult, clan names and territories and also some data on the enigmatic rongorongo

Rongorongo

Rongorongo is a system of glyphs discovered in the 19th century on Easter Island that appears to be writing or proto-writing. It cannot be read despite numerous attempts at decipherment. Although some calendrical and what might prove to be genealogical information has been identified, not even...

script; Van Tilburg credits her with a primary role in assisting preservation of Rapa Nui's indigenous Polynesian culture

Polynesian culture

Polynesian culture refers to the indigenous peoples' culture of Polynesia who share common traits in language, customs and society. Chronologically, the development of Polynesian culture can be divided into four different historical eras:...

.

German East Asia Squadron

The German East Asia Squadron was a German Navy cruiser squadron which operated mainly in the Pacific Ocean between the 1870s and 1914...

, including the armored cruiser

Armored cruiser

The armored cruiser was a type of warship of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Like other types of cruiser, the armored cruiser was a long-range, independent warship, capable of defeating any ship apart from a battleship, and fast enough to outrun any battleships it encountered.The first...

s Scharnhorst

SMS Scharnhorst

SMS Scharnhorst was an armored cruiser of the Imperial German Navy, built at the Blohm & Voss shipyard in Hamburg, Germany. She was the lead ship of her class, which also included her sister . Scharnhorst and her sister were enlarged versions of the preceding ; they were equipped with a greater...

and Gneisenau

SMS Gneisenau

SMS Gneisenau was an armored cruiser of the German navy, part of the two-ship . She was named after August von Gneisenau, a Prussian general of the Napoleonic Wars. The ship was laid down in 1904 at the AG Weser dockyard in Bremen, launched in June 1906, and completed in March 1908, at a cost of...

, and the light cruiser

Light cruiser

A light cruiser is a type of small- or medium-sized warship. The term is a shortening of the phrase "light armored cruiser", describing a small ship that carried armor in the same way as an armored cruiser: a protective belt and deck...

s Dresden, Leipzig

SMS Leipzig

SMS Leipzig was a Bremen class light cruiser, of the German Imperial Navy. It was named after the German city of Leipzig.The ship was stationed off the west coast of Mexico at the outbreak of war in 1914...

, Emden and rendezvoused off Hanga Roa

Hanga Roa

Hanga Roa is the main town, harbour and capital of the Chilean province of Easter Island. It is located in the southern part of the island's west coast, in the lowlands between the extinct volcanoes of Terevaka and Rano Kau....

. While the expedition covered up their main discoveries to hide them from the Germans, the Germans converted their fleet to a fighting trim. By the time the Germans landed 48 British and French merchant seamen from sunken prizes it had become clear to all that World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

had broken out, and Routledge complained sharply of this infringement of neutral Chile

Chile

Chile ,officially the Republic of Chile , is a country in South America occupying a long, narrow coastal strip between the Andes mountains to the east and the Pacific Ocean to the west. It borders Peru to the north, Bolivia to the northeast, Argentina to the east, and the Drake Passage in the far...

an territory to the schoolmaster in his capacity as representative of the Government of Chile

Chile

Chile ,officially the Republic of Chile , is a country in South America occupying a long, narrow coastal strip between the Andes mountains to the east and the Pacific Ocean to the west. It borders Peru to the north, Bolivia to the northeast, Argentina to the east, and the Drake Passage in the far...

; whilst her husband sailed the Mana to Valparaiso

Valparaíso

Valparaíso is a city and commune of Chile, center of its third largest conurbation and one of the country's most important seaports and an increasing cultural center in the Southwest Pacific hemisphere. The city is the capital of the Valparaíso Province and the Valparaíso Region...

to pass on a similar complaint to the British Consul in Santiago

Santiago, Chile

Santiago , also known as Santiago de Chile, is the capital and largest city of Chile, and the center of its largest conurbation . It is located in the country's central valley, at an elevation of above mean sea level...

. There is no record of what steps the schoolmaster took to persuade the German fleet to leave Chilean waters, but they did depart, most of them to Coronel

Battle of Coronel

The First World War naval Battle of Coronel took place on 1 November 1914 off the coast of central Chile near the city of Coronel. German Kaiserliche Marine forces led by Vice-Admiral Graf Maximilian von Spee met and defeated a Royal Navy squadron commanded by Rear-Admiral Sir Christopher...

and the Falklands. Some of the stranded French merchant seamen were recruited as labourers by the expedition. Routledge also decided to mediate in the native rebellion against the sheep ranch that was led by local medicine woman and visionary, Angata.

The Routledges departed the island in August, 1915 returning home via Pitcairn and San Francisco. She published her findings in a popular travel book, The Mystery of Easter Island, in 1919. Hundreds of the objects that she and her husband found are now in the Pitt Rivers Museum

Pitt Rivers Museum

The Pitt Rivers Museum is a museum displaying the archaeological and anthropological collections of the University of Oxford in Oxford, England. The museum is located to the east of the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, and can only be accessed through that building.The museum was...

, whilst her paper records are held by the Royal Geographical Society

Royal Geographical Society

The Royal Geographical Society is a British learned society founded in 1830 for the advancement of geographical sciences...

in London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

. Most of her scientific conclusions are accepted to this day.

Health

If as Tilburg suggested, from early childhood, Routledge had suffered from what is today believed to have been the developing stages of paranoid schizophrenia, it is surprising that she was able to get the valuable anthropolical research, often under arduous conditions involving living in close quarters with others for years, she did, with no sign of the condition. In her recent biography, Jo Anne Van TilburgJo Anne Van Tilburg

Jo Anne Van Tilburg is an American archaeologist best known for her research on the statues of Easter Island . Her primary specialty is rock art....

related that Katherine's brother, Harold Pease, also suffered from mental illness, although whether he also suffered from schizophrenia is unclear. She became involved with Spiritualism during her Oxford years and practiced automatic writing

Automatic writing

Automatic writing or psychography is writing which the writer states to be produced from a subconscious and/or spiritual source without conscious awareness of the content.-History:...

.

After 1925, her schizophrenia got worse and displayed itself in the form of delusion

Delusion

A delusion is a false belief held with absolute conviction despite superior evidence. Unlike hallucinations, delusions are always pathological...

al paranoia

Paranoia

Paranoia [] is a thought process believed to be heavily influenced by anxiety or fear, often to the point of irrationality and delusion. Paranoid thinking typically includes persecutory beliefs, or beliefs of conspiracy concerning a perceived threat towards oneself...

. She threw Scoresby out of her Hyde Park, London

Hyde Park, London

Hyde Park is one of the largest parks in central London, United Kingdom, and one of the Royal Parks of London, famous for its Speakers' Corner.The park is divided in two by the Serpentine...

mansion and locked herself inside. She also hid many of her field notes. Her family blamed Angata, accusing her of being a "witch doctor

Witch doctor

A witch doctor originally referred to a type of healer who treated ailments believed to be caused by witchcraft. It is currently used to refer to healers in some third world regions, who use traditional healing rather than contemporary medicine...

". In 1929 Scoresby and her family had her kidnapped against her will and confined to a mental institution. This diagnosis is contentious; Jo Anne Van Tilburg, for example in a recent lecture on the subject at the Royal Geographical Society, said that the Easter Islanders themselves displayed symptoms of paranoid schizophrenia, which is clearly at odds with anthropological understandings of Polynesian culture.

She died institutionalized in 1935. Her husband gave the field notes he found to the Royal Geographical Society. One of his executors found photographs of the Easter Island expedition ten years after his death. Maps of the expedition were found in Scoresby's house in Cyprus in 1961. Family papers and photographs, previously unpublished, including details of her illness, were made public through her recent biography. Archaeology on Easter Island continues to make use of her field notes and ethnographic research.