Humphry Berkeley

Encyclopedia

Humphry John Berkeley was a British

politician noted for his many changes of parties and his efforts to effect homosexual law reform, and both oppose, and then seem to abet, grand apartheid.

was Liberal

Member of Parliament

(MP) for Nottingham Central

from 1922

to 1924

and a noted playwright. Humphry Berkeley attended Malvern College

followed by Pembroke College, Cambridge

and was President of both the Cambridge Union Society

and Cambridge University Conservative Association

in 1948.

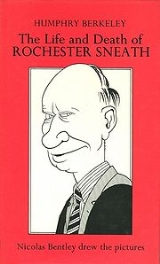

His studies were interrupted when he was excluded ('sent down') for two years as a result of a practical joke in which he impersonated 'H. Rochester Sneath

', the headmaster of a rather odd public school, and wrote hoax letters

to public figures. Berkeley knew Rab Butler

who arranged a job for him at Conservative Central Office during this time; he also advised him to keep the hoax letters and their replies safely, and publish them a quarter of a century later (the 'Rochester Sneath letters' were duly published in 1974, and have recently been republished by Harriman House in the UK).

in 1956-1957. In the 1959 general election

he was elected as a Conservative

MP for Lancaster

.

Berkeley was a strong internationalist who supported the work of the United Nations

and served on the Parliamentary Assembly of the Western European Union

and Council of Europe

from 1963. On the socially liberal wing of his party, Berkeley was a member of the Howard League for Penal Reform

and served as its hon. Treasurer from 1965. That year he also drew up the new rules for election of the Leader of the Conservative Party.

When he won second place in the ballot for Private Member's Bill

s in 1965, Berkeley decided to introduce a bill to legalise male homosexual relations

along the lines of the Wolfenden report

. Indeed, Berkeley was well known to his colleagues as a homosexual, according to a 2007 article published in The Observer

and not much liked. His Bill was given a second reading by 164 to 107 on 11 February 1966, but fell when Parliament was dissolved soon after. Unexpectedly, Berkeley lost his seat in the 1966 general election

, and ascribed his defeat to the unpopularity of his bill on homosexuality.

Out of Parliament, Berkeley took a job as Chairman of the United Nations Association

. In this capacity he employed Jeffrey Archer, who was establishing a reputation for raising large amounts of money for charities, to organise the UNA's flag day collection. Despite barely increasing the previous year's total, Archer was promoted to organise a dinner at 10 Downing Street

which raised over £200,000. However Berkeley became concerned and found that Archer was claiming on expenses for things he had not actually paid for. Knowing of Archer's ambition in the Conservative Party, Berkeley contacted Conservative Central Office to raise his concerns. No action was taken, but the allegations surfaced in the Press. Archer brought a defamation action against Berkeley as the source of the allegations. The case was settled out of court after three years.

In 1968 he had resigned from the Conservative Party, largely in opposition to its stance on the Vietnam War

. In 1970, he joined the Labour Party

and stood unsuccessfully as a Labour candidate in 1974.

He then spent time apparently working as a roving ambassador of the now defunct Republic of Transkei, a bantustan

, until he was abducted one night in February 1979 while dining at the Umtata Holiday Inn, and assaulted on the side of a road, put into the boot of a car, and dumped over the border at Kei Bridge.

As a moderate and pro-European he joined the SDP

in 1981, and fought Southend East

for them in 1987. In 1988 with the SDP splitting over whether to merge with the Liberals, he rejoined Labour.

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

politician noted for his many changes of parties and his efforts to effect homosexual law reform, and both oppose, and then seem to abet, grand apartheid.

Background and early life

Berkeley's father ReginaldReginald Berkeley (politician)

Reginald Cheyne Berkeley was a Liberal Party politician in the United Kingdom.He was elected as Member of Parliament for Nottingham Central at the 1922 general election, winning the seat with a majority of only 22 votes over the sitting Conservative MP Albert Atkey...

was Liberal

Liberal Party (UK)

The Liberal Party was one of the two major political parties of the United Kingdom during the 19th and early 20th centuries. It was a third party of negligible importance throughout the latter half of the 20th Century, before merging with the Social Democratic Party in 1988 to form the present day...

Member of Parliament

Member of Parliament

A Member of Parliament is a representative of the voters to a :parliament. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, the term applies specifically to members of the lower house, as upper houses often have a different title, such as senate, and thus also have different titles for its members,...

(MP) for Nottingham Central

Nottingham Central (UK Parliament constituency)

Nottingham Central was a borough constituency in the city of Nottingham. It returned one Member of Parliament to the House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom....

from 1922

United Kingdom general election, 1922

The United Kingdom general election of 1922 was held on 15 November 1922. It was the first election held after most of the Irish counties left the United Kingdom to form the Irish Free State, and was won by Andrew Bonar Law's Conservatives, who gained an overall majority over Labour, led by John...

to 1924

United Kingdom general election, 1924

- Seats summary :- References :* F. W. S. Craig, British Electoral Facts: 1832-1987* - External links :* * *...

and a noted playwright. Humphry Berkeley attended Malvern College

Malvern College

Malvern College is a coeducational independent school located on a 250 acre campus near the town centre of Malvern, Worcestershire in England. Founded on 25 January 1865, until 1992, the College was a secondary school for boys aged 13 to 18...

followed by Pembroke College, Cambridge

Pembroke College, Cambridge

Pembroke College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge, England.The college has over seven hundred students and fellows, and is the third oldest college of the university. Physically, it is one of the university's larger colleges, with buildings from almost every century since its...

and was President of both the Cambridge Union Society

Cambridge Union Society

The Cambridge Union Society, commonly referred to as simply "the Cambridge Union" or "the Union," is a debating society in Cambridge, England and is the largest society at the University of Cambridge. Since its founding in 1815, the Union has developed a worldwide reputation as a noted symbol of...

and Cambridge University Conservative Association

Cambridge University Conservative Association

The Cambridge University Conservative Association is a long-established political society going back to 1921, with roots in the late nineteenth century, as a Conservative branch for students at Cambridge University in England...

in 1948.

His studies were interrupted when he was excluded ('sent down') for two years as a result of a practical joke in which he impersonated 'H. Rochester Sneath

H. Rochester Sneath

H. Rochester Sneath MA L-ès-L was the nonexistent headmaster of the also nonexistent Selhurst School who wrote many bizarre letters to public figures in 1948. Selhurst supposedly had 175 male students....

', the headmaster of a rather odd public school, and wrote hoax letters

Hoax letter writers

- Henry Root :Henry Root is the creation of writer William Donaldson who wrote to numerous public figures with unusual or outlandish questions and requests...

to public figures. Berkeley knew Rab Butler

Rab Butler

Richard Austen Butler, Baron Butler of Saffron Walden, KG CH DL PC , who invariably signed his name R. A. Butler and was familiarly known as Rab, was a British Conservative politician...

who arranged a job for him at Conservative Central Office during this time; he also advised him to keep the hoax letters and their replies safely, and publish them a quarter of a century later (the 'Rochester Sneath letters' were duly published in 1974, and have recently been republished by Harriman House in the UK).

Career

Berkeley established his own public relations company and became head of publicity and public relations for a group of civil engineering companies. As a strong supporter of European union, he was Director-General of the United Kingdom Council of the European MovementEuropean Movement

The European Movement International is a lobbying association that coordinates the efforts of associations and national councils with the goal of promoting European integration, and disseminating information about it.-History:...

in 1956-1957. In the 1959 general election

United Kingdom general election, 1959

This United Kingdom general election was held on 8 October 1959. It marked a third successive victory for the ruling Conservative Party, led by Harold Macmillan...

he was elected as a Conservative

Conservative Party (UK)

The Conservative Party, formally the Conservative and Unionist Party, is a centre-right political party in the United Kingdom that adheres to the philosophies of conservatism and British unionism. It is the largest political party in the UK, and is currently the largest single party in the House...

MP for Lancaster

Lancaster (UK Parliament constituency)

Lancaster was a constituency of the House of Commons of the Parliament of England then of the Parliament of Great Britain from 1707 to 1800 and of the Parliament of the United Kingdom from 1801 to 1867, centred on the historic city of Lancaster in north-west England...

.

Berkeley was a strong internationalist who supported the work of the United Nations

United Nations

The United Nations is an international organization whose stated aims are facilitating cooperation in international law, international security, economic development, social progress, human rights, and achievement of world peace...

and served on the Parliamentary Assembly of the Western European Union

Western European Union

The Western European Union was an international organisation tasked with implementing the Modified Treaty of Brussels , an amended version of the original 1948 Treaty of Brussels...

and Council of Europe

Council of Europe

The Council of Europe is an international organisation promoting co-operation between all countries of Europe in the areas of legal standards, human rights, democratic development, the rule of law and cultural co-operation...

from 1963. On the socially liberal wing of his party, Berkeley was a member of the Howard League for Penal Reform

Howard League for Penal Reform

The Howard League for Penal Reform is a London-based registered charity in the United Kingdom. It is the oldest penal reform organisation in the world, named after John Howard. Founded in 1866 as the Howard Association, a merger with the Penal Reform League in 1921 created the Howard League for...

and served as its hon. Treasurer from 1965. That year he also drew up the new rules for election of the Leader of the Conservative Party.

When he won second place in the ballot for Private Member's Bill

Private Member's Bill

A member of parliament’s legislative motion, called a private member's bill or a member's bill in some parliaments, is a proposed law introduced by a member of a legislature. In most countries with a parliamentary system, most bills are proposed by the government, not by individual members of the...

s in 1965, Berkeley decided to introduce a bill to legalise male homosexual relations

Homosexuality

Homosexuality is romantic or sexual attraction or behavior between members of the same sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, homosexuality refers to "an enduring pattern of or disposition to experience sexual, affectional, or romantic attractions" primarily or exclusively to people of the same...

along the lines of the Wolfenden report

Wolfenden report

The Report of the Departmental Committee on Homosexual Offences and Prostitution was published in Britain on 4 September 1957 after a succession of well-known men, including Lord Montagu, Michael Pitt-Rivers and Peter Wildeblood, were convicted of homosexual offences.-The committee:The...

. Indeed, Berkeley was well known to his colleagues as a homosexual, according to a 2007 article published in The Observer

The Observer

The Observer is a British newspaper, published on Sundays. In the same place on the political spectrum as its daily sister paper The Guardian, which acquired it in 1993, it takes a liberal or social democratic line on most issues. It is the world's oldest Sunday newspaper.-Origins:The first issue,...

and not much liked. His Bill was given a second reading by 164 to 107 on 11 February 1966, but fell when Parliament was dissolved soon after. Unexpectedly, Berkeley lost his seat in the 1966 general election

United Kingdom general election, 1966

The 1966 United Kingdom general election on 31 March 1966 was called by sitting Labour Prime Minister Harold Wilson. Wilson's decision to call an election turned on the fact that his government, elected a mere 17 months previously in 1964 had an unworkably small majority of only 4 MPs...

, and ascribed his defeat to the unpopularity of his bill on homosexuality.

Out of Parliament, Berkeley took a job as Chairman of the United Nations Association

United Nations Association UK

right|The United Nations Association of the UK is the leading independent policy authority on the UN in the UK and a UK-wide grassroots membership organisation.-Activities:...

. In this capacity he employed Jeffrey Archer, who was establishing a reputation for raising large amounts of money for charities, to organise the UNA's flag day collection. Despite barely increasing the previous year's total, Archer was promoted to organise a dinner at 10 Downing Street

10 Downing Street

10 Downing Street, colloquially known in the United Kingdom as "Number 10", is the headquarters of Her Majesty's Government and the official residence and office of the First Lord of the Treasury, who is now always the Prime Minister....

which raised over £200,000. However Berkeley became concerned and found that Archer was claiming on expenses for things he had not actually paid for. Knowing of Archer's ambition in the Conservative Party, Berkeley contacted Conservative Central Office to raise his concerns. No action was taken, but the allegations surfaced in the Press. Archer brought a defamation action against Berkeley as the source of the allegations. The case was settled out of court after three years.

In 1968 he had resigned from the Conservative Party, largely in opposition to its stance on the Vietnam War

Vietnam War

The Vietnam War was a Cold War-era military conflict that occurred in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. This war followed the First Indochina War and was fought between North Vietnam, supported by its communist allies, and the government of...

. In 1970, he joined the Labour Party

Labour Party (UK)

The Labour Party is a centre-left democratic socialist party in the United Kingdom. It surpassed the Liberal Party in general elections during the early 1920s, forming minority governments under Ramsay MacDonald in 1924 and 1929-1931. The party was in a wartime coalition from 1940 to 1945, after...

and stood unsuccessfully as a Labour candidate in 1974.

He then spent time apparently working as a roving ambassador of the now defunct Republic of Transkei, a bantustan

Bantustan

A bantustan was a territory set aside for black inhabitants of South Africa and South West Africa , as part of the policy of apartheid...

, until he was abducted one night in February 1979 while dining at the Umtata Holiday Inn, and assaulted on the side of a road, put into the boot of a car, and dumped over the border at Kei Bridge.

As a moderate and pro-European he joined the SDP

Social Democratic Party (UK)

The Social Democratic Party was a political party in the United Kingdom that was created on 26 March 1981 and existed until 1988. It was founded by four senior Labour Party 'moderates', dubbed the 'Gang of Four': Roy Jenkins, David Owen, Bill Rodgers and Shirley Williams...

in 1981, and fought Southend East

Southend East (UK Parliament constituency)

Southend East was a parliamentary constituency in Essex. It returned one Member of Parliament to the House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom....

for them in 1987. In 1988 with the SDP splitting over whether to merge with the Liberals, he rejoined Labour.