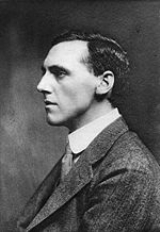

Frederick Septimus Kelly

Encyclopedia

Frederick Septimus Kelly (29 May 1881 – 13 November 1916) was an Australia

n and British

musician and composer and a rower

who competed in the 1908 Summer Olympics

. He was killed in action during the First World War.

, Australia

. He was educated at Sydney Grammar School

then sent to England and educated at Eton College

, where he stroked the school eight to victory in the Ladies' Challenge Plate

at Henley Royal Regatta

in 1899.

Kelly was awarded a Lewis Nettleship musical scholarship at Oxford in this year, and went up to Balliol College, Oxford

(B.A., 1903; M.A., 1912), became president of the university musical club and a leading spirit at the Sunday evening concerts at Balliol. He was a protege of Ernest Walker.

while at Oxford and won the Diamond Challenge Sculls

at Henley in 1902, beating Raymond Etherington-Smith

in the final.

He rowed in the four seat for Oxford

against Cambridge

in the 1903 Boat Race. Oxford lost the race by 6 lengths. Kelly went on to win the Diamond sculls at Henley again that summer, beating Jack Beresford

in the final. He also won the Wingfield Sculls, the Amateur Championship of the Thames, beating the holder Arthur Cloutte

. This was the only occasion on which he entered.

On leaving Oxford in 1903 he starting rowing at Leander Club

and was in the Leander crews which won the Grand Challenge Cup

at Henley in 1903, 1904 and 1905 and the Stewards' Challenge Cup

in 1906. In 1905 he again won the Diamond sculls, beating Harry Blackstaffe

. His time on this occasion 8 min. 10 sec. stood as a record for over 30 years.

Kelly's last appearance in a racing boat was in 1908, when he competed at the London Olympic Games. He was a member of the Leander crew in the eights

, which won the gold medal for Great Britain rowing at the 1908 Summer Olympics

.

Contemporary reports of Kelly's oarsmanship were glowing: 'his natural sense of poise and rhythm made his boat a live thing under him'. In his book stating that "Many think [Kelly] the greatest amateur stylist of all time".

at the Hoch Conservatory

in Frankfurt, and on his return to London acted as an adviser to the Classical Concert Society and used his influence in favour of the recognition of modern composers. In 1911 he visited Sydney and gave some concerts, and in 1912 took part in chamber music concerts in London.

Following the outbreak of war in 1914, Kelly was commissioned into the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve for service with the Royal Naval Division with his friends—the poet Rupert Brooke

, the critic and composer William Denis Browne

, and others of what became known as the Latin Club.

Kelly was wounded twice at Gallipoli

, where he was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross

and reached the rank of lieutenant-commander. At Gallipoli he wrote his scores in his tent at base camp, including his tribute to Brooke, Elegy for String Orchestra: "In Memoriam Rupert Brooke" (1915), conceived in the wake of Brooke's death. Kelly was among the party who buried him on Skyros.

The following is a description of Kelly's close connection to Brooke, taken from

Race Against Time: the Diaries of F.S. Kelly:

Kelly survived the Gallipoli slaughter, only to die at Beaucourt-sur-l'Ancre

, France

, when rushing a German machine gun post in the last days of the Battle of the Somme in November 1916. He lies in Martinsart's British Cemetery not far from where he fell at the age of 35.

At the memorial concert held at the Wigmore Hall

, London

, on 2 May 1919, some of his piano compositions were played by Leonard Borwick

, and some of his songs were sung by Muriel Foster

; but his "Elegy for String Orchestra", written at Gallipoli in memory of Rupert Brooke, a work of profound feeling, stood out from his other compositions, and made a deep impression. His papers are held in the National Library of Australia

.

Kelly's "Serenade for Flute" with accompaniment of Harp, Horn, and String Orchestra (opus 7), written in 1911 has received its first recording 100 years after he composed it. It also has made a deep impression, on the Canadian flautist Rebecca Hall, who has recorded it for CD label Cameo Classics. José

Garcia Gutierrez was the horn soloist, with the Malta Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by its Musical Director, Michael Laus. The CD (CC9032CD) also features orchestral compositions by Kelly's near contemporary British composers - Scott, Gaze Cooper, Holbrooke, and Blower - and is available on line from www.cameo-classics.com

Unmarried, he had lived at his home Bisham Grange, near Marlow

, Buckinghamshire, with his sister Mary (Maisie). There is a memorial to him in the village of Bisham

.

His elder brother William Henry Kelly

was a politician who held the seat of Wentworth

in the Australian House of Representatives

from 1903 to 1919.

Australia

Australia , officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country in the Southern Hemisphere comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It is the world's sixth-largest country by total area...

n and British

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

musician and composer and a rower

Rowing (sport)

Rowing is a sport in which athletes race against each other on rivers, on lakes or on the ocean, depending upon the type of race and the discipline. The boats are propelled by the reaction forces on the oar blades as they are pushed against the water...

who competed in the 1908 Summer Olympics

1908 Summer Olympics

The 1908 Summer Olympics, officially the Games of the IV Olympiad, were an international multi-sport event which was held in 1908 in London, England, United Kingdom. These games were originally scheduled to be held in Rome. At the time they were the fifth modern Olympic games...

. He was killed in action during the First World War.

Early life

Kelly, the fourth son of Irish-born woolbroker Thomas Herbert Kelly and his native-born wife Mary Anne, née Dick, was born in 1881 at 47 Phillip Street, SydneySydney

Sydney is the most populous city in Australia and the state capital of New South Wales. Sydney is located on Australia's south-east coast of the Tasman Sea. As of June 2010, the greater metropolitan area had an approximate population of 4.6 million people...

, Australia

Australia

Australia , officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country in the Southern Hemisphere comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It is the world's sixth-largest country by total area...

. He was educated at Sydney Grammar School

Sydney Grammar School

Sydney Grammar School is an independent, non-denominational, selective, day school for boys, located in Darlinghurst, Edgecliff and St Ives, all suburbs of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia....

then sent to England and educated at Eton College

Eton College

Eton College, often referred to simply as Eton, is a British independent school for boys aged 13 to 18. It was founded in 1440 by King Henry VI as "The King's College of Our Lady of Eton besides Wyndsor"....

, where he stroked the school eight to victory in the Ladies' Challenge Plate

Ladies' Challenge Plate

The Ladies' Challenge Plate is one of the events at Henley Royal Regatta on the River Thames at Henley-on-Thames in England. Crews of men's eight-oared boats below the standard of the Grand Challenge Cup can enter, although international standard heavyweight crews are not permitted to row in the...

at Henley Royal Regatta

Henley Royal Regatta

Henley Royal Regatta is a rowing event held every year on the River Thames by the town of Henley-on-Thames, England. The Royal Regatta is sometimes referred to as Henley Regatta, its original name pre-dating Royal patronage...

in 1899.

Kelly was awarded a Lewis Nettleship musical scholarship at Oxford in this year, and went up to Balliol College, Oxford

Balliol College, Oxford

Balliol College , founded in 1263, is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England but founded by a family with strong Scottish connections....

(B.A., 1903; M.A., 1912), became president of the university musical club and a leading spirit at the Sunday evening concerts at Balliol. He was a protege of Ernest Walker.

Rowing

Kelly took up scullingSculling

Sculling generally refers to a method of using oars to propel watercraft in which the oar or oars touch the water on both the port and starboard sides of the craft, or over the stern...

while at Oxford and won the Diamond Challenge Sculls

Diamond Challenge Sculls

The Diamond Challenge Sculls is a rowing event for men's single sculls at the annual Henley Royal Regatta on the River Thames at Henley-on-Thames in England...

at Henley in 1902, beating Raymond Etherington-Smith

Raymond Etherington-Smith

Raymond Broadley Etherington-Smith was a British doctor and rower who competed in the 1908 Summer Olympics.Etherington-Smith was born at Putney...

in the final.

He rowed in the four seat for Oxford

Oxford University Boat Club

The Oxford University Boat Club is the rowing club of the University of Oxford, England, located on the River Thames at Oxford. The club was founded in the early 19th century....

against Cambridge

Cambridge University Boat Club

The Cambridge University Boat Club is the rowing club of the University of Cambridge, England, located on the River Cam at Cambridge, although training primarily takes place on the River Great Ouse at Ely. The club was founded in 1828...

in the 1903 Boat Race. Oxford lost the race by 6 lengths. Kelly went on to win the Diamond sculls at Henley again that summer, beating Jack Beresford

Jack Beresford

Jack Beresford, CBE, was a British rower who won medals at five Olympic Games in succession, an Olympic record in rowing, which has since been tied by Steven Redgrave.-Early life:...

in the final. He also won the Wingfield Sculls, the Amateur Championship of the Thames, beating the holder Arthur Cloutte

Arthur Cloutte

Arthur Hamilton Cloutte was an English rower who won the Wingfield Sculls, the amateur single sculling championship of the River Thames, in 1902...

. This was the only occasion on which he entered.

On leaving Oxford in 1903 he starting rowing at Leander Club

Leander Club

Leander Club, founded in 1818, is one of the oldest rowing clubs in the world. It is based in Remenham in the English county of Berkshire, adjoining Henley-on-Thames...

and was in the Leander crews which won the Grand Challenge Cup

Grand Challenge Cup

The Grand Challenge Cup is a rowing competition for men's eights. It is the oldest and most prestigious event at the annual Henley Royal Regatta on the River Thames at Henley-on-Thames in England. It is open to male crews from all eligible rowing clubs...

at Henley in 1903, 1904 and 1905 and the Stewards' Challenge Cup

Stewards' Challenge Cup

The Stewards' Challenge Cup is a rowing event for men's coxless fours at the annual Henley Royal Regatta on the River Thames at Henley-on-Thames in England. It is open to male crews from all eligible rowing clubs. Two or more clubs may combine to make an entry....

in 1906. In 1905 he again won the Diamond sculls, beating Harry Blackstaffe

Harry Blackstaffe

Henry Thomas "Harry" Blackstaffe was a British rower who competed in the 1908 Summer Olympics.Blackstaffe was born in Islington, London, and became a butcher. He was a long-standing member of Vesta Rowing Club in Putney and also a cross-country runner who represented South London Harriers in the...

. His time on this occasion 8 min. 10 sec. stood as a record for over 30 years.

Kelly's last appearance in a racing boat was in 1908, when he competed at the London Olympic Games. He was a member of the Leander crew in the eights

Eight (rowing)

An Eight is a rowing boat used in the sport of competitive rowing. It is designed for eight rowers, who propel the boat with sweep oars, and is steered by a coxswain, or cox....

, which won the gold medal for Great Britain rowing at the 1908 Summer Olympics

Rowing at the 1908 Summer Olympics

At the 1908 Summer Olympics, four rowing events were contested, all for men only. Races were held at Henley-on-Thames. The competitions were held from July 28, 1908 to July 31, 1908. There was one fewer event in 1908 than 1904, after the double sculls was dropped from the programme...

.

Contemporary reports of Kelly's oarsmanship were glowing: 'his natural sense of poise and rhythm made his boat a live thing under him'. In his book stating that "Many think [Kelly] the greatest amateur stylist of all time".

Life after Oxford

After leaving Oxford with fourth-class honours in history, Kelly studied the piano under Iwan KnorrIwan Knorr

Iwan Knorr was a German composer and teacher of music. A native of Mewe, he attended the Leipzig Conservatory where he studied with Ignaz Moscheles, Ernst Friedrich Richter and Carl Reinecke. In 1874 he became a teacher and in 1878 director of music theory instruction at the Imperial...

at the Hoch Conservatory

Hoch Conservatory

Dr. Hoch’s Konservatorium - Musikakademie was founded in Frankfurt am Main on September 22, 1878. Through the generosity of Frankfurter Joseph Hoch, who bequeathed the Conservatory one million German gold marks in his testament, a school for music and the arts was established for all age groups. ...

in Frankfurt, and on his return to London acted as an adviser to the Classical Concert Society and used his influence in favour of the recognition of modern composers. In 1911 he visited Sydney and gave some concerts, and in 1912 took part in chamber music concerts in London.

Following the outbreak of war in 1914, Kelly was commissioned into the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve for service with the Royal Naval Division with his friends—the poet Rupert Brooke

Rupert Brooke

Rupert Chawner Brooke was an English poet known for his idealistic war sonnets written during the First World War, especially The Soldier...

, the critic and composer William Denis Browne

William Denis Browne

William Charles Denis Browne , primarily known as Billy to family and as Denis to his friends, was a British composer, pianist, organist and music critic of the early 20th century. He and his close friend, poet Rupert Brooke, were commissioned into the Royal Naval Division together shortly after...

, and others of what became known as the Latin Club.

Kelly was wounded twice at Gallipoli

Gallipoli

The Gallipoli peninsula is located in Turkish Thrace , the European part of Turkey, with the Aegean Sea to the west and the Dardanelles straits to the east. Gallipoli derives its name from the Greek "Καλλίπολις" , meaning "Beautiful City"...

, where he was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross

Distinguished Service Cross (United Kingdom)

The Distinguished Service Cross is the third level military decoration awarded to officers, and other ranks, of the British Armed Forces, Royal Fleet Auxiliary and British Merchant Navy and formerly also to officers of other Commonwealth countries.The DSC, which may be awarded posthumously, is...

and reached the rank of lieutenant-commander. At Gallipoli he wrote his scores in his tent at base camp, including his tribute to Brooke, Elegy for String Orchestra: "In Memoriam Rupert Brooke" (1915), conceived in the wake of Brooke's death. Kelly was among the party who buried him on Skyros.

The following is a description of Kelly's close connection to Brooke, taken from

Race Against Time: the Diaries of F.S. Kelly:

Kelly survived the Gallipoli slaughter, only to die at Beaucourt-sur-l'Ancre

Beaucourt-sur-l'Ancre

Beaucourt-sur-l'Ancre is a commune in the Somme department in Picardie in northern France.-Geography:The commune is situated south of Arras on the D50 and D163 junction. The Ancre river is little more than a trickle through marshy ground at this point....

, France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

, when rushing a German machine gun post in the last days of the Battle of the Somme in November 1916. He lies in Martinsart's British Cemetery not far from where he fell at the age of 35.

At the memorial concert held at the Wigmore Hall

Wigmore Hall

Wigmore Hall is a leading international recital venue that specialises in hosting performances of chamber music and is best known for classical recitals of piano, song and instrumental music. It is located at 36 Wigmore Street, London, UK and was built to provide London with a venue that was both...

, London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

, on 2 May 1919, some of his piano compositions were played by Leonard Borwick

Leonard Borwick

Leonard Borwick was an English concert pianist especially associated with the music of Robert Schumann and Johannes Brahms.- Early training and debuts :...

, and some of his songs were sung by Muriel Foster

Muriel Foster

Muriel Foster was an English contralto, excelling in oratorio. Grove's Dictionary describes her voice as "one of the most beautiful voices of her time"....

; but his "Elegy for String Orchestra", written at Gallipoli in memory of Rupert Brooke, a work of profound feeling, stood out from his other compositions, and made a deep impression. His papers are held in the National Library of Australia

National Library of Australia

The National Library of Australia is the largest reference library of Australia, responsible under the terms of the National Library Act for "maintaining and developing a national collection of library material, including a comprehensive collection of library material relating to Australia and the...

.

Kelly's "Serenade for Flute" with accompaniment of Harp, Horn, and String Orchestra (opus 7), written in 1911 has received its first recording 100 years after he composed it. It also has made a deep impression, on the Canadian flautist Rebecca Hall, who has recorded it for CD label Cameo Classics. José

Garcia Gutierrez was the horn soloist, with the Malta Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by its Musical Director, Michael Laus. The CD (CC9032CD) also features orchestral compositions by Kelly's near contemporary British composers - Scott, Gaze Cooper, Holbrooke, and Blower - and is available on line from www.cameo-classics.com

Unmarried, he had lived at his home Bisham Grange, near Marlow

Marlow, Buckinghamshire

Marlow is a town and civil parish within Wycombe district in south Buckinghamshire, England...

, Buckinghamshire, with his sister Mary (Maisie). There is a memorial to him in the village of Bisham

Bisham

Bisham is a village and civil parish in the Windsor and Maidenhead district of Berkshire, England. According to the 2001 census it had a population of 1,149. The village is on the River Thames, north of which is Marlow in Buckinghamshire...

.

His elder brother William Henry Kelly

William Kelly (Australian politician)

William Henry Kelly was an Australian politician.Kelly was born in Sydney and educated at All Saints College, Bathurst, and Eton College from 1893 to 1896...

was a politician who held the seat of Wentworth

Division of Wentworth

The Division of Wentworth is an Australian Electoral Division in the state of New South Wales. It was proclaimed in 1900 and was one of the original 75 divisions contested at the first federal election. The Division is named after William Charles Wentworth , a noted Australian explorer and statesman...

in the Australian House of Representatives

Australian House of Representatives

The House of Representatives is one of the two houses of the Parliament of Australia; it is the lower house; the upper house is the Senate. Members of Parliament serve for terms of approximately three years....

from 1903 to 1919.

Compositions

- Two Songs, Op. 1 (1902)

- Waltz-pageant Op. 2 for piano; arranged for two pianos (1905 rev. 1911)

- Allegro de concert, Op. 3 for piano (1907)

- A Cycle of Lyrics, Op. 4 for piano (1908)

- Theme, Variations and Fugue, Op. 5 for two pianos (1907-11)

- Six Songs, Op. 6 (1910-13)

- Serenade for flute, harp and strings, Op. 7 (1911)

- String Trio (1913-14)

- Two Preludes for organ (1914)

- Elegy, In Memoriam Rupert Brooke for harp and strings (1915)

- Violin Sonata in G Major "Gallipoli" (1915)

- Piano Sonata in F minor- unfinished (1916)