Council of Troubles

Encyclopedia

Fernando Álvarez de Toledo, 3rd Duke of Alba

Don Fernando Álvarez de Toledo y Pimentel, 3rd Duke of Alba was a Spanish general and governor of the Spanish Netherlands , nicknamed "the Iron Duke" in the Low Countries because of his harsh and cruel rule there and his role in the execution of his political opponents and the massacre of several...

, governor-general of the Habsburg Netherlands

Habsburg Netherlands

The Habsburg Netherlands was a geo-political entity covering the whole of the Low Countries from 1482 to 1556/1581 and solely the Southern Netherlands from 1581 to 1794...

on the orders of Philip II of Spain

Philip II of Spain

Philip II was King of Spain, Portugal, Naples, Sicily, and, while married to Mary I, King of England and Ireland. He was lord of the Seventeen Provinces from 1556 until 1581, holding various titles for the individual territories such as duke or count....

to punish the ringleaders of the recent political and religious "troubles" in the Netherlands. Because of the many death sentences pronounced by the tribunal, it also became known as the Council of Blood (Bloedraad in Dutch and Conseil de Sang in French). The tribunal would be abolished by Alba's successor Luis de Zúñiga y Requesens

Luis de Zúñiga y Requesens

Luis de Requesens y Zúñiga also known as Luis de Zúñiga y Requesens was a Spanish politician and diplomat.-Biography:Luis de Requesens y Zúñiga was born at Molins de Rei...

on June 7, 1574 in exchange for a subsidy from the States-General of the Netherlands

States-General of the Netherlands

The States-General of the Netherlands is the bicameral legislature of the Netherlands, consisting of the Senate and the House of Representatives. The parliament meets in at the Binnenhof in The Hague. The archaic Dutch word "staten" originally related to the feudal classes in which medieval...

, but in practice it remained in session until the popular revolution in Brussels of the summer of 1576.

Background

During the final two years of the regency of Margaret of ParmaMargaret of Parma

Margaret, Duchess of Parma , Governor of the Netherlands from 1559 to 1567 and from 1578 to 1582, was the illegitimate daughter of Charles V and Johanna Maria van der Gheynst...

over the Habsburg Netherlands political (disaffection of the high nobility with its diminished role in the councils of state), religious (disaffection over the persecution of heretics and the reform of the organisation of the Catholic Church in the Netherlands, especially the creation of new dioceses), and economic circumstances (a famine in 1565) conspired to bring about a number of political and social events that shook the regime to its foundations. A League of Nobles

Compromise of Nobles

The Compromise'of Nobles was a covenant of members of the lesser nobility in the Habsburg Netherlands who came together to submit a petition to the Regent Margaret of Parma on 5 April 1566, with the objective of obtaining a moderation of the placards against heresy in the Netherlands...

(mostly members of the lower nobility) protested the severity of the persecution of heretics with a petition to the Regent, who conceded the demands temporarily. This may have encouraged the Calvinists in the country to follow the iconoclastic depradations on Catholic churches that also burst out in France in the summer of 1566. Though this Iconoclastic fury was soon suppressed by the authorities, and the concessions to the Calvinists retracted, these "troubles" sufficiently disturbed the Court in Madrid to motivate Philip to send his trusted commander, the Duke of Alba, with an army of Spanish mercenaries to "restore order" in the Netherlands. When he arrived there, his first measures so offended the Regent that she resigned in protest in early September, 1567.

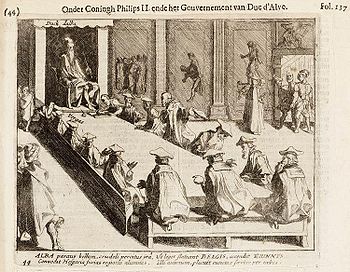

Patent instituting the Council

One of these measures was the institution (Sept. 9, 1567) of a council to investigate and punish the events described above. This council was only later to become known as the "Council of Troubles," as for the moment it was presented as just an advisory council, next to the three collateral Habsburg councils (Council of State, Privy Council, and Council of Finances), and the High Court at MechelenMechelen

Mechelen Footnote: Mechelen became known in English as 'Mechlin' from which the adjective 'Mechlinian' is derived...

. The fact, however, that it superseded these preexisting councils for this express purpose, and that the new tribunal (as it turned out to be) ignored the judicial privileges enshrined in such constitutional documents as the Joyeuses entrées

Royal Entry

The Royal Entry, also known by various other names, including Triumphal Entry and Joyous Entry, embraced the ceremonial and festivities accompanying a formal entry by a ruler or his representative into a city in the Middle Ages and Early Modern Period in Europe...

of the ancient Duchy of Brabant

Duchy of Brabant

The Duchy of Brabant was a historical region in the Low Countries. Its territory consisted essentially of the three modern-day Belgian provinces of Flemish Brabant, Walloon Brabant and Antwerp, the Brussels-Capital Region and most of the present-day Dutch province of North Brabant.The Flag of...

(which Philip had affirmed on his accession to the ducal throne in 1556), shocked the constitutional conscience of the Regent, and the Dutch politicians.

Initially, the council was composed of the Duke himself (as president), assisted by two high Netherlandish nobles, Charles de Berlaymont

Charles de Berlaymont

Charles de Berlaymont was a noble who sided with the Spanish during the Eighty years war, and was a member of the Council of Troubles. He was the son of Michiel de Berlaymont and Maria de Berault. He was lord of Floyon and Haultpenne, and baron of Hierges...

(the alleged author of the epithet Geuzen

Geuzen

Geuzen was a name assumed by the confederacy of Calvinist Dutch nobles and other malcontents, who from 1566 opposed Spanish rule in the Netherlands. The most successful group of them operated at sea, and so were called Watergeuzen...

)http://dutchrevolt.leidenuniv.nl/Nederlands/personen/b/berlaymont.htm and Philippe de Noircarmes

Philip of Noircarmes

Philip of Noircarmes, whose full name was: Philippe René Nivelon Louis de Sainte-Aldegonde, Lord of Noircarmes was a statesman and soldier from the Habsburg Netherlands in the service of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor and Philip II of Spain...

(as vice-presidents). Members were a number of prominent jurists, recruited from the Councils of the provinces, like Adrianus Nicolai (chancellor of Guelders), Jacob Meertens (president of the council of Artois), Pieter Asset, Jacob Hessels (councillor of Ghent

Ghent

Ghent is a city and a municipality located in the Flemish region of Belgium. It is the capital and biggest city of the East Flanders province. The city started as a settlement at the confluence of the Rivers Scheldt and Lys and in the Middle Ages became one of the largest and richest cities of...

), and his colleague Johan de la Porte (advocaat-fiscaal of Flanders). Jean du Bois, procureur-generaal at the High Court became chief prosecutor.

The most important members, however, were two Spaniards, who came with Alba from Spain: Juan de Vargas http://dutchrevolt.leidenuniv.nl/Nederlands/personen/v/vargas.htm and Luis del Rio http://dutchrevolt.leidenuniv.nl/Nederlands/personen/d/delriolouis.htm. Jacques de la Torre (a secretary of the Privy Council) became the principal secretary of the new council. Only these Spanish members apparently had the right to vote on verdicts. Vargas played, informally, a leading role within the council as he prepared the agenda and he vetted all draft verdicts before they were presented to the governor-general for final disposition.

Organization and procedure

At first, the council acted as an advisory council of the Duke, who decided on all verdicts himself. As the number of cases grew into the thousands in the years following the early sensational trials, this was not practicable. Alba therefore instituted two criminal and two civil Chambers for the Council in 1569, and expanded the number of councillors appreciably, at the same time replacing a few councillors (like the Burgundian Claude Belin), who had shown an undesirable degree of independence. The most important of the new members was the new secretary Jeronimo de Roda http://dutchrevolt.leidenuniv.nl/Nederlands/personen/r/roda.htm, who received the same powers as Vargas and Del Rio.The criminal cases were apportioned to the two criminal chambers on a regional basis. The civil chambers were charged with the many appeals against confiscations of the material goods that were usually part of the death sentences or sentences of perpetual banishment. The management of these forfeited possessions was also an important task of the civil chambers. The case load was nevertheless so overwhelming, that at the time of the formal abolition of the council a staggering 14,000 cases were still undecided.

Besides its judicial functions, the Council also had an important advisory role in the attempts at codification of criminal law, that the government of Alba made in the early 1570s. Because of the development of the Revolt, these laudable attempts came to nothing, however.

After the initial, rather chaotic period, the procedure followed in trials was that all criminal courts had to report cases within the remit of the council (heresy and treason) to the council. Depending on the importance of the case, the council would then either leave the case to the lower court for settlement, or take it up itself. In case the matter was called-up from the lower court, it would either be settled by the council itself, or the lower court would receive instructions about the sentence it would have to pronounce.

The government did not leave the prosecutions to chance in the lower courts, however. From the beginning, commissioners were sent out to the provinces to actively pursue heretics and political undesiderables. Those commissioners were an important source of cases, and they also functioned as provincial annexes of the central council in Brussels.

The trials were conducted completely in writing. Written indictments were produced that had to be answered in writing by the defendants. The verdicts were in writing also.

The verdicts generally had little basis in law as it was understood at the time. The accusation was usually crimen laesae majestatis or high treason. This, of course, was a crime well-founded in Roman law (which was still followed in the Netherlands at the time). But the exact content was nebulous. The councillors (and Alba himself) apparently made it up as they went, according to the exigencies of the situation. No wonder many contemporaries viewed the proceedings as purely arbitrary. The fact that the proceedings seem to have been guided only by verbal instructions of Alba, did little to ameliorate this impression.

Notorious cases

The most notorious cases were those of the political elite of the Netherlands. Alba indicted most members of the former Council of State in late 1567. Most indictees (like William the SilentWilliam the Silent

William I, Prince of Orange , also widely known as William the Silent , or simply William of Orange , was the main leader of the Dutch revolt against the Spanish that set off the Eighty Years' War and resulted in the formal independence of the United Provinces in 1648. He was born in the House of...

) had gone abroad for their health, but two prominent members Lamoral, Count of Egmont

Lamoral, Count of Egmont

Lamoral, Count of Egmont, Prince of Gavere was a general and statesman in the Habsburg Netherlands just before the start of the Eighty Years' War, whose execution helped spark the national uprising that eventually led to the independence of the Netherlands.The Count of Egmont headed one of the...

and Philip de Montmorency, Count of Hoorn

Philip de Montmorency, Count of Hoorn

Philip de Montmorency was also known as Count of Horn or Hoorne or Hoorn.-Biography:De Montmorency was born, between 1518 and 1526, possibly at the Ooidonk Castle, as the son of Jozef van Montmorency, Count of Nevele and Anna van Egmont...

were apprehended in December, 1567. Despite the fact that they were members of the Order of the Golden Fleece

Order of the Golden Fleece

The Order of the Golden Fleece is an order of chivalry founded in Bruges by Philip III, Duke of Burgundy in 1430, to celebrate his marriage to the Portuguese princess Infanta Isabella of Portugal, daughter of King John I of Portugal. It evolved as one of the most prestigious orders in Europe...

, and claimed the privilege to be tried by their peers, Philip denied this claim, and they were tried and convicted by the Council of Troubles.

Both were sentenced to death and executed on June 5, 1568.

But these were only the most eminent victims. According to Jonathan Israel

Jonathan Israel

Professor Jonathan Irvine Israel is a British writer on Dutch history, the Age of Enlightenment and European Jewry. Israel was appointed the Modern European History Professor in the School of Historical Studies at the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton Township, New Jersey, U.S...

, 8950 individuals, from all levels of society, were convicted of heresy or treason. As most of these were tried in absentia, however, only about 1,000 of these sentences were carried out. The other convicts had to live in exile, their possessions confiscated.

Alba's main objectives with the activities of the Council seem to have been to institute a reign of terror among what he saw as the enemies of the Regime, and to make money for the depleted coffers of that Regime.

As regards the first objective: four days before the execution of the Counts of Egmont and Hoorn there was the wholesale execution of eighteen lesser nobles (among whom the three brothers Bronckhorst van Batenburg) in Brussels. Many other nobles, especially from Holland, where a large part of the ridderschap had been implicated in the League of Nobles, fled abroad (still forfeiting their lands). Among those were Willem Bloys van Treslong (who would in 1572 capture Den Briel), Gijsbrecht van Duivenvoorde (who would be a prominent defender in the siege of Haarlem in 1573), Jacob van Duivenvoorde (later a prominent defender of Leiden in 1574) and Willem van Zuylen van Nijevelt

Van Zuylen van Nijevelt

Van Zuylen van Nijevelt This family must not be confused with the old noble family from Utrecht, Van Zuylen van Nievelt-Origins:During the 19th C. members of this family tried to prove that they were descendants of the Utrecht noble family. This has later been found impossible to prove.Their...

(a Utrecht iconoclast). But members of the urban patriciate were also persecuted. The Advocate of the States of Holland

States of Holland

The States of Holland and West Frisia were the representation of the two Estates to the court of the Count of Holland...

, Jacob van den Eynde was arrested, but died in captivity before his trial ended. In Haarlem Dirck Volckertszoon Coornhert

Dirck Volckertszoon Coornhert

Dirck Volckertszoon Coornhert was a Dutch writer, philosopher, translator, politician and theologian. Coornhert is often considered the Father of Dutch Renaissance scholarship.-Biography:...

was arrested, but he managed to escape, Lenaert Jansz de Graeff

Lenaert Jansz de Graeff

Lenaert Jansz de Graeff , was a member of the family De Graeff and the son of Jan Pietersz Graeff, a rich cloth merchant from Amsterdam...

from Amsterdam fled to Brugge

Brügge

Brügge is a municipality in the district of Rendsburg-Eckernförde, in Schleswig-Holstein, Germany.Its small church and market square are noted for their beauty....

and became later captain of the Sea Beggers in the Capture of Brielle

Capture of Brielle

The Capture of Brielle by the Sea Beggars, or Watergeuzen, on 1 April 1572 marked a turning point in the uprising of the Low Countries against Spain in the Eighty Years' War. Militarily the success was minor, as Brielle was not being defended at the time...

. Others, like Jan van Casembroot

Jan van Casembroot

Jan van Casembroot was a South-Holland noble and poet. He was lord of Bekkerzeel, Zellik, Kobbegem, Berchem and Fenain.-Life:...

(from Bruges) and Anthonie van Straelen (from Antwerp) were less fortunate.

Many more lesser-known people were engulfed in the wholesale condemnations that the Council issued like clockwork. The first were 84 inhabitants of Valenciennes

Valenciennes

Valenciennes is a commune in the Nord department in northern France.It lies on the Scheldt river. Although the city and region had seen a steady decline between 1975 and 1990, it has since rebounded...

(then still part of the Netherlands) on January 4, 1568; followed on February 20 by 95 people from several places in Flandres; February 21: 25 inhabitants of Thielt and 46 of Mechelen etc. etc.. The impression this made did not miss its effect: thousands of people somehow related to the Calvinist religion now fled to more congenial places. Examples would be many families in Amsterdam (De Graeff

De Graeff

De Graeff is an old Dutch patrician family. The family have played an important role during the Dutch Golden Age. They were at the centre of Amsterdam public life and oligarchy from 1578 until 1672...

, Bicker, Reael, Huydecoper van Maarsseveen, Pauw, and Hooft) and Middelburg (Boreel, Van der Perre, Van Vosbergen) who would later become prominent Regent

Regenten

In the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, the regenten were the rulers of the Dutch Republic, the leaders of the Dutch cities or the heads of organisations . Though not formally a hereditary "class", they were de facto "patricians", comparable to that ancient Roman class...

families in those cities. The exodus proceeded in two main waves: in the Spring of 1567 (of those who did not await Alba's arrival), and again after a round of wholesale arrests, in the Winter of 1567/68. The total number of people involved has been estimated at 60,000.

Alba had hoped that the confiscations that accompanied the condemnations would be an important source of income for the Crown. But in this respect he was to be disappointed, also because Philip directed him to pay new pensions from the proceeds to people who had served the Crown well in previous years. Besides, the families of the condemned didn't take the confiscations lying down. The civil chambers of the Council were swamped with claims concerning the legality of the confiscations. Nevertheless, the proceeds reached half a million ducats annually according to a letter from the Spanish ambassador in France to Philip in 1572.

Abolition

After Alba's replacement with Requesens as governor-general the Council continued its work. However, it became more and more clear that its proceedings were counterproductive as a means to combat the Rebellion. Philip therefore authorized Requesens to abolish the Council in 1574, if the States General were prepared to make adequate political concessions. After the promise of a large subsidy by the States General the Council was formally abolished by Requesens on June 7, 1574, contingent, however, on payment of the subsidy.Aftermath

As the subsidy remained unpaid, the Council remained in being during the remainder of the reign of Requesens. No more death sentences were pronounced, however. After Requesens death in March, 1576 a power vacuum ensued. The Council of State now demanded to see the instructions and records of the tribunal. However, the secretary, De Roda, replied that there were no written instructions. When asked how the council had managed to try and condemn so many people, he said that the council had condemned nobody: all sentences were pronounced by the governors-general themselves; the council had technically only prepared the drafts.On September 4, 1576, revolutionary bands, led by Jacques de Glimes, bailli of Brabant, arrested the members of the Council of State (the acting Brussels government). This ended at the same time the Council of Troubles (which the Council of State had not dared to disperse). Unfortunately, a large part of the archives of the council were lost shortly after this action. This may also have something to do with the fact that the sentences of the Council were quashed as a consequence of the amnesty, contained in the Pacification of Ghent

Pacification of Ghent

The Pacification of Ghent, signed on November 8, 1576, was an alliance of the provinces of the Habsburg Netherlands for the purpose of driving mutinying Spanish mercenary troops from the country, and at the same time a peace treaty with the rebelling provinces Holland and Zeeland.-Background:In...

which was concluded shortly afterwards. Fortunately, many duplicates are still extant in Spanish archives. Prominent members of the council were arrested by the Rebels, like Del Rio (who was sent to the headquarters of the Prince of Orange, but was later exchanged), and the notorious Hessels (who was summarily hanged by the revolutionary Ghent government). Others, however, escaped the revenge of the people, like the Spaniards Vargas and De Roda.