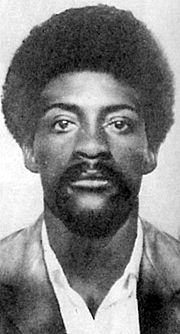

Bunchy Carter

Encyclopedia

African American

African Americans are citizens or residents of the United States who have at least partial ancestry from any of the native populations of Sub-Saharan Africa and are the direct descendants of enslaved Africans within the boundaries of the present United States...

activist who was killed on January 17, 1969. He is celebrated by his supporters as a martyr

Martyr

A martyr is somebody who suffers persecution and death for refusing to renounce, or accept, a belief or cause, usually religious.-Meaning:...

in the Black Power

Black Power

Black Power is a political slogan and a name for various associated ideologies. It is used in the movement among people of Black African descent throughout the world, though primarily by African Americans in the United States...

movement in the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

.

Early history

In the early 1960s Carter was a member of the Slauson street gang in Los AngelesLos Ángeles

Los Ángeles is the capital of the province of Biobío, in the commune of the same name, in Region VIII , in the center-south of Chile. It is located between the Laja and Biobío rivers. The population is 123,445 inhabitants...

. He became a member of the Slauson "Renegades", a hard-core inner circle of the gang, and earned the nickname "Mayor of the Ghetto". Carter was eventually convicted of armed robbery and was imprisoned in Soledad prison for four years. While incarcerated Carter became influenced by the Nation of Islam

Nation of Islam

The Nation of Islam is a mainly African-American new religious movement founded in Detroit, Michigan by Wallace D. Fard Muhammad in July 1930 to improve the spiritual, mental, social, and economic condition of African-Americans in the United States of America. The movement teaches black pride and...

and the teachings of Malcolm X

Malcolm X

Malcolm X , born Malcolm Little and also known as El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz , was an African American Muslim minister and human rights activist. To his admirers he was a courageous advocate for the rights of African Americans, a man who indicted white America in the harshest terms for its...

, and he converted to Islam

Islam

Islam . The most common are and . : Arabic pronunciation varies regionally. The first vowel ranges from ~~. The second vowel ranges from ~~~...

. After his release, Carter met Huey Newton, one of the founders of the Black Panther Party

Black Panther Party

The Black Panther Party wasan African-American revolutionary leftist organization. It was active in the United States from 1966 until 1982....

, and was convinced to join the party in 1967. In early 1968 Carter formed the Southern California chapter of the Black Panthers and became a leader in the group. Like all Black Panther chapters, the Southern California chapter studied politics, read BPP literature, and received training in firearm

Firearm

A firearm is a weapon that launches one, or many, projectile at high velocity through confined burning of a propellant. This subsonic burning process is technically known as deflagration, as opposed to supersonic combustion known as a detonation. In older firearms, the propellant was typically...

s and first aid

First aid

First aid is the provision of initial care for an illness or injury. It is usually performed by non-expert, but trained personnel to a sick or injured person until definitive medical treatment can be accessed. Certain self-limiting illnesses or minor injuries may not require further medical care...

. They also began the "Free Breakfast for Children

Free Breakfast for Children

In January, 1969, the Free Breakfast for School Children Program was initiated at St. Augustine's Church in Oakland by the Black Panther Party. The Panthers would cook and serve food to the poor inner city youth of the area. Initially run out of a St...

" program which provided meals to the poor in the community. The chapter was very successful, gaining 50–100 new members each week by April 1968. Notable members included Elaine Brown

Elaine Brown

Elaine Brown is an American prison activist, writer, singer, and former Black Panther leader who is based in Oakland, California. She is a former chairperson of the Black Panther Party. Brown briefly ran for the Green Party presidential nomination in 2008...

, and Geronimo Pratt

Geronimo Pratt

Geronimo Ji Jaga , also known as Geronimo ji-Jaga Pratt born: Elmer Pratt, was a high ranking member of the Black Panther Party...

.

The Southern California chapter of the Black Panthers

The Black Panthers were opposed by the secret FBI operation COINTELPROCOINTELPRO

COINTELPRO was a series of covert, and often illegal, projects conducted by the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation aimed at surveilling, infiltrating, discrediting, and disrupting domestic political organizations.COINTELPRO tactics included discrediting targets through psychological...

, and the party was referred to as "the greatest threat to the internal security of the country" by J. Edgar Hoover

J. Edgar Hoover

John Edgar Hoover was the first Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation of the United States. Appointed director of the Bureau of Investigation—predecessor to the FBI—in 1924, he was instrumental in founding the FBI in 1935, where he remained director until his death in 1972...

. As revealed later in Senate testimony, the FBI worked with the Los Angeles Police Department

Los Angeles Police Department

The Los Angeles Police Department is the police department of the city of Los Angeles, California. With just under 10,000 officers and more than 3,000 civilian staff, covering an area of with a population of more than 4.1 million people, it is the third largest local law enforcement agency in...

to harass and intimidate party members. In 1968 and 1969, numerous false arrests and warrantless searches were documented, and several members were killed in altercations with the police. The "Breakfast for Children" program was effectively shut down by daily arrests of members; however, these charges were most often dropped within a week. "The Breakfast for Children Program," wrote Hoover in an internal FBI memo in May 1969, "represents the best and most influential activity going for the BPP and, as such, is potentially the greatest threat to efforts by authorities to neutralize the BPP and destroy what it stands for." Later that year, Hoover submitted orders to FBI offices: "exploit all avenues of creating dissension within the ranks of the BPP," and "submit imaginative and hard-hitting counterintelligence measures aimed at crippling the BPP."

The Black Panthers were also rivals of a black nationalist group named Organization Us, founded by Ron Karenga

Ron Karenga

Maulana Karenga is an African-American professor of Africana Studies, scholar/activist, author and best known as the creator of the pan-African and African American holiday of Kwanzaa...

. The groups had very different aims and tactics, but the groups often found themselves competing for potential recruits. This rivalry came to a head in 1969, when the two groups supported different candidates to head the Afro-American Studies Center at UCLA.

The killings

John Huggins

John Huggins was an American civil rights activist and leader in the Los Angeles chapter of the Black Panther Party.-Biography:...

, another BPP member, were heard making derogatory comments about Karenga, the founder of Us. Other versions mention a heated argument between Us members and Panther Elaine Brown. An altercation ensued during which Carter and Huggins were shot to death.

BPP members insisted that the event was a planned assassination, whereas Us members maintained it was a spontaneous event. Former BPP deputy minister of defense Geronimo Pratt, Carter’s head of security at the time, has stated in recent years that rather than a conspiracy, the UCLA incident was a spontaneous shootout. The person who allegedly shot Carter and Huggins, Claude Hubert, was never found. Later, during the Church Committee

Church Committee

The Church Committee is the common term referring to the United States Senate Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities, a U.S. Senate committee chaired by Senator Frank Church in 1975. A precursor to the U.S...

hearings in 1975, evidence came to light that under the FBI's COINTELPRO actions, FBI agents had deliberately fanned flames of division and enmity between the BPP and Us. Death threats and humiliating cartoons created by the FBI were sent to each group, made to look as if they originated with the other group, with the explicit intention of inciting deadly violence and division.

Following the UCLA incident, brothers George and Larry Stiner and Donald Hawkins turned themselves in to the police, who had issued warrants for their arrests. They were convicted for conspiracy to commit murder and two counts of second-degree murder, based on testimony given by BPP members. The Stiner brothers both received life sentences and Hawkins served time in California’s Youth Authority Detention.

The Stiners escaped from San Quentin in 1974. George is at large to this day. Larry survived as a fugitive for 20 years, living in Suriname

Suriname

Suriname , officially the Republic of Suriname , is a country in northern South America. It borders French Guiana to the east, Guyana to the west, Brazil to the south, and on the north by the Atlantic Ocean. Suriname was a former colony of the British and of the Dutch, and was previously known as...

. He surrendered in 1994 in order to try to negotiate help for his destitute children in Suriname. He was immediately returned to San Quentin where he continues to serve out his life sentence. His children remained in precarious and impoverished circumstances for eleven years, until they finally were able to come to the U.S. in 2005.

Repercussions

The LAPD responded to the attack by raiding an apartment used by the Black Panthers and arresting 75 members, including all remaining leadership of the chapter, on charges of conspiring to murder Us members in retaliation. (These charges were later dropped.) This reaction fueled claims that Us was being used by the FBI to target the Black Panthers. Later in 1969, two other Black Panther members were killed and one other was wounded by Us members.The Black Student Union at UCLA was shocked and devastated by the murders and ceased to operate effectively on campus for several years. Richard Held was promoted to the special agent in charge of the San Francisco office.

In the years following the deaths of Carter and Huggins, the Black Panther party became more suspicious of outsiders and became more focused on defense rather than community improvement. The group was more marginalized and officially disbanded in 1980.

Bunchy Carter had a son who was born in April 1969, after Carter was murdered. His son, coincidentally, attended California State Long Beach (1987–1992), while Ron Karenga was the chairman of the Black Studies Department.