Antimafia Commission

Encyclopedia

The Italian Antimafia Commission is a bicameral commission of the Italian Parliament

, composed of members from the Chamber of Deputies

(Italian: Camera dei Deputati) and the Senate

(Italian: Senato della Repubblica). The Antimafia Commission is a commission of inquiry into, initially, the “phenomenon of the Mafia

”. Subsequent commissions investigated “organized crime of the Mafia type”, which included other Italian criminal organizations such as the Camorra

, the 'Ndrangheta and the Sacra Corona Unita

.

Its task is to study the phenomenon of organized crime in all its permutations and to measure the appropriateness of existing measures, legislatively and administratively, against results. The Commission has judicial powers in that it may instruct the judicial police to carry out investigations, it can ask for copies of court proceedings and is entitled to ask for any form of collaboration that it deems necessary. Those who provide testimony to the Commission are obliged to tell the truth. The Commission can report to Parliament as often as desired, but at least on an annual basis.

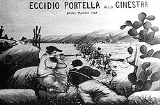

was the result of post-war struggles for land reform and the violent reaction against peasant organizations and its leaders, culminating in the killing of 11 people and the wounding of over thirty at a May 1

labour day parade in Portella della Ginestra. The attack was attributed to the bandit and separatist leader Salvatore Giuliano

. Nevertheless, the Mafia was suspected of involvement in the Portella della Ginestra massacre

and many other previous and subsequent attacks.

On September 14, 1948, a Parliamentary commission of inquiry into the public security situation on Sicily (Commissione parlamentare d'inchiesta sulla situazione dell'ordine pubblico) was proposed by deputy Giuseppe Berti of the Italian Communist Party

(PCI) in a debate on the violence in Sicily. However, the proposal was turned down by Minister of the Interior, Mario Scelba

, amidst indignant voices about prejudice against Sicily and Sicilians.

Ten years later, in 1958, senator Ferruccio Parri

again proposed to form a Commission. The proposal was not taken up by the parliamentary majority and in 1961 the Christian Democrat party (DC - Democrazia Cristiana) in the Senate and Sicilian politicians like Bernardo Mattarella

and Giovanni Gioia (both later accused of links with the Mafia) dismissed the proposal as useless. However, in March 1962, amidst gang wars in Palermo

, the Sicilian Assembly asked for an official inquiry. On April 11, 1962, the Senate in Rome approved the bill, but it took eight months before the Chamber of Deputies put the law to a vote. It was finally approved it on December 20, 1962.

(Partito Socialista Democratico Italiano, PSDI). It took a long time to form because newspapers and parliamentarians alike were opposed to the inclusion of Sicilians. It lasted less than three months before the general elections of April 28, 1963.

The second president in the new legislature

was the Christian Democrat Donato Pafundi, and was formed on June 5, 1963. Later that month, on June 30, 1963, a car bomb exploded in Ciaculli

, an outlying suburb of Palermo

, killing seven police and military officers sent to defuse it after an anonymous phone call. The bomb was intended for Salvatore "Ciaschiteddu" Greco, head of the Sicilian Mafia Commission

and the boss of the Ciaculli Mafia family. The Ciaculli massacre

changed the Mafia war into a war against the Mafia. It prompted the first concerted anti-mafia efforts by the state in post-war Italy. On July 6, 1963 the Antimafia Commission met for the first time. It would take 13 years and two more legislatures before a final report was submitted in 1976.

The PCI

claimed the Christian Democrat party (DC) put members on the Commission to stop the inquiry moving too far in the political field, such as the Commission’s vice-president Antonio Gullotti and Giovanni Matta, a former member of the Palermo

city council. Matta’s arrival in 1972 created a scandal, he had been mentioned in a report and was summoned to testify in the previous legislature about the role of the Mafia in real estate speculation. The PCI called for his resignation, and in the end the whole Commission under the presidency of Luigi Carraro had to resign and be recomposed without Matta again.

However, the efficacy of the new law was severely limited. Firstly, because there was no legal definition of a Mafia association. Secondly, because the obligation for mafiosi to reside in areas outside Sicily, actually opened up new opportunities to develop illicit activities in the cities of northern and central Italy.

Cattanei came under attack of his fellow Christian Democrats. The party’s official newspaper, Il Popolo, wrote that the Commission had become an instrument of the Communists. Everything was tried to smear his reputation, but supported by the majority of the Commission and public opinion he resisted the pressure to resign. In July 1971 the Commission published an intermediary report with biographies of prominent mafiosi such as Tommaso Buscetta

and summarized the characteristics of the Mafia

.

The Commission investigated the activities and failed prosecution of Luciano Leggio

, the administration of Palermo

and the wholesale markets in the city, as well as the links between the Mafia and banditry in the post-War period. In its report of March 1972, the Commission said in its introduction: “Generally speaking magistrates, trade unionists, prefects, journalists and the police authorities expressed an affirmative judgement on the existence of more or less intimate links between Mafia and the public authorities … some trade unionists reached the point of saying that ‘the mafioso is a man of politics’.” The Commission’s main conclusion was that the Mafia was strong because it had penetrated the structure of the State.

The Commission was dissolved when new elections made an end to the legislature. In the next legislature, Cattanei was replaced with Luigi Carraro, a Christian Democrat that was more sensitive to the fears of the Christian Democrat Party that had been under attack of the Commission.

In 1972 Cesare Terranova

In 1972 Cesare Terranova

, previously chief investigative prosecutor in Palermo who had prepared several Mafia Trials in the 1960s, such as the Trial of the 114, that had ended with disappointing little convictions. He was elected for the Independent Left under the auspices of the Italian Communist Party

(PCI). He became the secretary of the Commission. Terranova, together with PCI deputy Pio La Torre

, wrote the minority report of the Commission, which pointed to links between the Mafia

and prominent politicians, in particular of the Christian Democrat party (DC - Democrazia Cristiana).

Terranova had urged his colleagues of the majority to take their responsibility. According to the minority report:

In the final report of the first Commission, the former mayor of Palermo

, Salvo Lima was described as one of the pillars of Mafia power in Palermo

. It had no formal consequences for Lima. (In 1993 the fourth Commission led by Luciano Violante

concluded that there were strong indications of relations between Lima and members of Cosa Nostra. By then Lima had been killed by the Mafia

). In its conclusions, the Commission made many recommendations and offered much advice to those bodies that were going to take the job on. It criticized some authorities and condemned others. The government did nothing, however. When the results were published, every effort was made to confuse their message and diminish their value, and drowned in a sea of slander. The reports and the documentation of the Antimafia Commission were essentially disregarded. Terranova would talk of “thirteen wasted years” of the Antimafia Commission.

The final report was issued at a time when the question of the Mafia was pushed to the background by the political turmoil in the 1970s, known as the years of lead (it

: anni di piombo), a period characterized by widespread social conflicts and terrorism acts attributed to far-right and far-left political movements and the secret services.

The second Antimafia Commission was installed on September 13, 1982, in the midst of the Second Mafia War

The second Antimafia Commission was installed on September 13, 1982, in the midst of the Second Mafia War

, after the killing of former deputy and member of the first Antimafia Commission, Pio La Torre

, on April 30, 1982, and the prefect of Palermo

, general Carlo Alberto Dalla Chiesa

on September 3, 1982. The first president was the Christian Democrat senator Nicola La Penta, who was succeeded by the Communist deputy Abdon Alinovi.

The Commission had no power to investigate. It analysed Antimafia legislation, in particular the new Antimafia law (known as the Rognoni-La Torre law) and the performance of the state and judicial authorities. While the Commission was in function, the Maxi Trial

against the Mafia took place in Palermo

. The Commission also analysed new developments in Cosa Nostra after their entry in drug trafficking. The Commission was dissolved at the end of the legislature in July 1987.

. This Commission marked a change in operations: the focus shifted from analyses and knowledge about the Mafia to proposals at the legislative and administrative level. The Commission studied the connections between the four Mafia-type organizations and the links between the Mafia and secret Masonic lodges. It lobbied for the introduction of new legislation such as the reform of the Rognoni-La Torre law whereby asset seizure and confiscation provisions were applicable to other forms of criminal association including drug trafficking, extortion

and usury

among others.

The third Commission decided to make public the 2.750 files on links between the Mafia and politicians that had been kept secret by the first Commission. Looking ahead to the general elections of April 5, 1992, in February 1992 the Commission urged political parties to apply a code of self-regulation when presenting candidates, a measure intended to mirror the legislative provisions for public-office holders in 1990: no one should stand for election who had been committed for trial, was a fugitive from the law, was serving a criminal sentence, was subject to preventive measures or was convicted, even though not definitively, for crimes of corruption, Mafia association and a range of others.

A week before the election the Commission reported that on the basis of information received from two-thirds of the prefectures in the country, 33 candidates standing in the forthcoming elections were ‘non presentable’ according to the code of self-regulation.

on May 23 and was modified after the killing of his colleague Paolo Borsellino

on July 19. On September 23, Luciano Violante

from the Democratic Party of the Left

(Partito democratico della Sinistra, PDS) was appointed president of the Commission. Under Violante’s leadership the Commission worked for 17 months until the dissolution of Parliament in February 1994. It passed 13 reports, but its most important one was on the relations between the Mafia

and politics, the so-called terzo livello (third level) of the Mafia

, on April 6, 1993.

The Commission had to work in one of Italy’s most critical moment when the country’s democracy was challenged by criminal subversion by the Mafia and the Mani pulite

investigation that unravelled Tangentopoli

(Italian

for bribeville), the corruption

-based political system that dominated Italy

. Despite the political sensitive nature of the Commission’s work, Violante’s greatest achievement was that the most important reports were backed by all major parties instead, as in the past, of producing majority (government) and minority (opposition) reports on the same theme.

Important pentiti

like Tommaso Buscetta

, Antonio Calderone, Leonardo Messina

and Gaspare Mutolo

gave testimonies. It found that Salvo Lima, a former Christian Democrat

mayor of Palermo

who was murdered in March 1992, had been linked to the Mafia and that former Prime Minister Giulio Andreotti

had been Lima's "political contact" in Rome. On November 16, 1992 Tommaso Buscetta

testified before the Antimafia Commission. "Salvo Lima was, in fact, the politician to whom Cosa Nostra turned most often to resolve problems for the organisation whose solution lay in Rome," Buscetta said. Other collaborating witnesses confirmed that Lima had been specifically ordered to "fix" the appeal of the Maxi Trial

with Italy's Supreme Court and had been murdered because he failed to do so.

Gaspare Mutolo

warned the Commission in February 1993 of the likelihood that further attacks were being planned by the Corleonesi

on the mainland.

The Senate authorized to proceed with the criminal investigation of Giulio Andreotti

on June 10, 1993 (he was formally committed for trial in Palermo on March 2, 1995).

(1994–1996), Ottaviano Del Turco

, from the Italian Democratic Socialists

(1996–1999), Giuseppe Lumia

, from the Democratic Left

(2000–2001), Roberto Centaro from Forza Italia

(2001–2006), Francesco Forgione

from the Communist Refoundation Party

(2006–2008). Currently the president is Giuseppe Pisanu

.

Parliament of Italy

The Parliament of Italy is the national parliament of Italy. It is a bicameral legislature with 945 elected members . The Chamber of Deputies, with 630 members is the lower house. The Senate of the Republic is the upper house and has 315 members .Since 2005, a party list electoral law is being...

, composed of members from the Chamber of Deputies

Italian Chamber of Deputies

The Italian Chamber of Deputies is the lower house of the Parliament of Italy. It has 630 seats, a plurality of which is controlled presently by liberal-conservative party People of Freedom. Twelve deputies represent Italian citizens outside of Italy. Deputies meet in the Palazzo Montecitorio. A...

(Italian: Camera dei Deputati) and the Senate

Italian Senate

The Senate of the Republic is the upper house of the Italian Parliament. It was established in its current form on 8 May 1948, but previously existed during the Kingdom of Italy as Senato del Regno , itself a continuation of the Senato Subalpino of Sardinia-Piedmont established on 8 May 1848...

(Italian: Senato della Repubblica). The Antimafia Commission is a commission of inquiry into, initially, the “phenomenon of the Mafia

Mafia

The Mafia is a criminal syndicate that emerged in the mid-nineteenth century in Sicily, Italy. It is a loose association of criminal groups that share a common organizational structure and code of conduct, and whose common enterprise is protection racketeering...

”. Subsequent commissions investigated “organized crime of the Mafia type”, which included other Italian criminal organizations such as the Camorra

Camorra

The Camorra is a Mafia-type criminal organization, or secret society, originating in the region of Campania and its capital Naples in Italy. It is one of the oldest and largest criminal organizations in Italy, dating to the 18th century.-Background:...

, the 'Ndrangheta and the Sacra Corona Unita

Sacra corona unita

Sacra Corona Unita, or United Sacred Crown, is a Mafia-like criminal organization from Apulia region in Southern Italy, and is especially active in the areas of Brindisi, Lecce and Taranto .-Background and activities:...

.

Its task is to study the phenomenon of organized crime in all its permutations and to measure the appropriateness of existing measures, legislatively and administratively, against results. The Commission has judicial powers in that it may instruct the judicial police to carry out investigations, it can ask for copies of court proceedings and is entitled to ask for any form of collaboration that it deems necessary. Those who provide testimony to the Commission are obliged to tell the truth. The Commission can report to Parliament as often as desired, but at least on an annual basis.

Preceding events

The first proposal to constitute a commission of inquiry into the MafiaMafia

The Mafia is a criminal syndicate that emerged in the mid-nineteenth century in Sicily, Italy. It is a loose association of criminal groups that share a common organizational structure and code of conduct, and whose common enterprise is protection racketeering...

was the result of post-war struggles for land reform and the violent reaction against peasant organizations and its leaders, culminating in the killing of 11 people and the wounding of over thirty at a May 1

Labour Day

Labour Day or Labor Day is an annual holiday to celebrate the economic and social achievements of workers. Labour Day has its origins in the labour union movement, specifically the eight-hour day movement, which advocated eight hours for work, eight hours for recreation, and eight hours for...

labour day parade in Portella della Ginestra. The attack was attributed to the bandit and separatist leader Salvatore Giuliano

Salvatore Giuliano

Salvatore Giuliano was a Sicilian peasant. It has been suggested that the subjugated social status of his class led him to become a bandit and separatist. He was mythologised during his life and after his death...

. Nevertheless, the Mafia was suspected of involvement in the Portella della Ginestra massacre

Portella della Ginestra massacre

The Portella della Ginestra massacre was one of the more violent acts of in the history of modern Italian politics, when 11 people were killed and 33 wounded during May Day celebrations in Sicily on May 1, 1947, in the municipality of Piana degli Albanesi...

and many other previous and subsequent attacks.

On September 14, 1948, a Parliamentary commission of inquiry into the public security situation on Sicily (Commissione parlamentare d'inchiesta sulla situazione dell'ordine pubblico) was proposed by deputy Giuseppe Berti of the Italian Communist Party

Italian Communist Party

The Italian Communist Party was a communist political party in Italy.The PCI was founded as Communist Party of Italy on 21 January 1921 in Livorno, by seceding from the Italian Socialist Party . Amadeo Bordiga and Antonio Gramsci led the split. Outlawed during the Fascist regime, the party played...

(PCI) in a debate on the violence in Sicily. However, the proposal was turned down by Minister of the Interior, Mario Scelba

Mario Scelba

Mario Scelba was an Italian Christian Democratic politician who served as the 34th Prime Minister of Italy from February 1954 to July 1955...

, amidst indignant voices about prejudice against Sicily and Sicilians.

Ten years later, in 1958, senator Ferruccio Parri

Ferruccio Parri

Ferruccio Parri was an Italian partisan and politician who served as the 43rd Prime Minister of Italy for several months in 1945. During the resistance he was known as Maurizio.-Biography:...

again proposed to form a Commission. The proposal was not taken up by the parliamentary majority and in 1961 the Christian Democrat party (DC - Democrazia Cristiana) in the Senate and Sicilian politicians like Bernardo Mattarella

Bernardo Mattarella

Bernardo Mattarella was an Italian politician for the Christian Democrat party . He has been Minister of Italy several times...

and Giovanni Gioia (both later accused of links with the Mafia) dismissed the proposal as useless. However, in March 1962, amidst gang wars in Palermo

Palermo

Palermo is a city in Southern Italy, the capital of both the autonomous region of Sicily and the Province of Palermo. The city is noted for its history, culture, architecture and gastronomy, playing an important role throughout much of its existence; it is over 2,700 years old...

, the Sicilian Assembly asked for an official inquiry. On April 11, 1962, the Senate in Rome approved the bill, but it took eight months before the Chamber of Deputies put the law to a vote. It was finally approved it on December 20, 1962.

The first Commission

The first Parliamentary Commission of Inquiry on the Mafia phenomenon in Sicily (Italian: Commissione parlamentare d'inchiesta sul fenomeno della mafia in Sicilia) was formed in February 1963, in the midst of the First Mafia War, under the presidency of Paolo Rossi of the Italian Democratic Socialist PartyItalian Democratic Socialist Party

The Italian Democratic Socialist Party is a minor social-democratic political party in Italy. Mimmo Magistro is the party leader. The PSDI, before the 1990s decline in votes and members, had been an important force in Italian politics, being the longest serving partner in government for Christian...

(Partito Socialista Democratico Italiano, PSDI). It took a long time to form because newspapers and parliamentarians alike were opposed to the inclusion of Sicilians. It lasted less than three months before the general elections of April 28, 1963.

The second president in the new legislature

Legislature

A legislature is a kind of deliberative assembly with the power to pass, amend, and repeal laws. The law created by a legislature is called legislation or statutory law. In addition to enacting laws, legislatures usually have exclusive authority to raise or lower taxes and adopt the budget and...

was the Christian Democrat Donato Pafundi, and was formed on June 5, 1963. Later that month, on June 30, 1963, a car bomb exploded in Ciaculli

Ciaculli

Ciaculli is an outlying suburb of Palermo, Sicily in Italy. It counts less than 5000 residents. Ciaculli is close to the suburb of Croceverde. Ciaculli has been important within the history of the Cosa Nostra. The best known Mafia family is the Greco Mafia clan...

, an outlying suburb of Palermo

Palermo

Palermo is a city in Southern Italy, the capital of both the autonomous region of Sicily and the Province of Palermo. The city is noted for its history, culture, architecture and gastronomy, playing an important role throughout much of its existence; it is over 2,700 years old...

, killing seven police and military officers sent to defuse it after an anonymous phone call. The bomb was intended for Salvatore "Ciaschiteddu" Greco, head of the Sicilian Mafia Commission

Sicilian Mafia Commission

The Sicilian Mafia Commission, known as Commissione or Cupola, is a body of leading Mafia members to decide on important questions concerning the actions of, and settling disputes within the Sicilian Mafia or Cosa Nostra...

and the boss of the Ciaculli Mafia family. The Ciaculli massacre

Ciaculli massacre

The Ciaculli massacre on 30 June 1963 was caused by a car bomb that exploded in Ciaculli, an outlying suburb of Palermo, killing seven police and military officers sent to defuse it after an anonymous phone call. The bomb was intended for Salvatore "Ciaschiteddu" Greco, head of the Sicilian Mafia...

changed the Mafia war into a war against the Mafia. It prompted the first concerted anti-mafia efforts by the state in post-war Italy. On July 6, 1963 the Antimafia Commission met for the first time. It would take 13 years and two more legislatures before a final report was submitted in 1976.

The PCI

Italian Communist Party

The Italian Communist Party was a communist political party in Italy.The PCI was founded as Communist Party of Italy on 21 January 1921 in Livorno, by seceding from the Italian Socialist Party . Amadeo Bordiga and Antonio Gramsci led the split. Outlawed during the Fascist regime, the party played...

claimed the Christian Democrat party (DC) put members on the Commission to stop the inquiry moving too far in the political field, such as the Commission’s vice-president Antonio Gullotti and Giovanni Matta, a former member of the Palermo

Palermo

Palermo is a city in Southern Italy, the capital of both the autonomous region of Sicily and the Province of Palermo. The city is noted for its history, culture, architecture and gastronomy, playing an important role throughout much of its existence; it is over 2,700 years old...

city council. Matta’s arrival in 1972 created a scandal, he had been mentioned in a report and was summoned to testify in the previous legislature about the role of the Mafia in real estate speculation. The PCI called for his resignation, and in the end the whole Commission under the presidency of Luigi Carraro had to resign and be recomposed without Matta again.

New legislation

In September 1963 the Commission presented a draft law, passed by Parliament in May 1965 as Law 575 entitled ‘Dispositions against the Mafia’, the first time the word Mafia had been used in legislation. The law extended 1956 legislation concerning individuals considered to be ‘socially dangerous’ to those ‘suspected of belonging to associations of the Mafia type’. The measures included special surveillance; the possibility of ordering a suspect to reside in a designed place outside his home area and the suspension of publicly issued licenses, grants or authorizations. The law gave powers to a public prosecutor or questor (chief of police) to identify and trace the assets of anyone suspected of involvement in a Mafia-type association.However, the efficacy of the new law was severely limited. Firstly, because there was no legal definition of a Mafia association. Secondly, because the obligation for mafiosi to reside in areas outside Sicily, actually opened up new opportunities to develop illicit activities in the cities of northern and central Italy.

Interim reports

In 1966 Pafundi declared: “These rooms here are like an ammunition store. In order to give us the chance to the very root of the truth we don’t want them to explode too soon. We have here a load of dynamite.” However, the store never exploded, and in March 1968 Pafundi summed up the efforts of the Commission in three discreet pages. All the documents were locked away. Pafundi’s successor who took over the Commission in 1968 was a different man. Francesco Cattanei was a Christian Democrat from the north of Italy and he was determined to investigate thoroughly.Cattanei came under attack of his fellow Christian Democrats. The party’s official newspaper, Il Popolo, wrote that the Commission had become an instrument of the Communists. Everything was tried to smear his reputation, but supported by the majority of the Commission and public opinion he resisted the pressure to resign. In July 1971 the Commission published an intermediary report with biographies of prominent mafiosi such as Tommaso Buscetta

Tommaso Buscetta

Tommaso Buscetta was a Sicilian mafioso. Although he was not the first pentito in the Italian witness protection program, he is widely recognized as the first important one breaking omertà...

and summarized the characteristics of the Mafia

Mafia

The Mafia is a criminal syndicate that emerged in the mid-nineteenth century in Sicily, Italy. It is a loose association of criminal groups that share a common organizational structure and code of conduct, and whose common enterprise is protection racketeering...

.

The Commission investigated the activities and failed prosecution of Luciano Leggio

Luciano Leggio

Luciano Leggio was an Italian criminal and leading figure of the Sicilian Mafia. He was the head of the Corleonesi, the Mafia faction that originated in the town of Corleone...

, the administration of Palermo

Palermo

Palermo is a city in Southern Italy, the capital of both the autonomous region of Sicily and the Province of Palermo. The city is noted for its history, culture, architecture and gastronomy, playing an important role throughout much of its existence; it is over 2,700 years old...

and the wholesale markets in the city, as well as the links between the Mafia and banditry in the post-War period. In its report of March 1972, the Commission said in its introduction: “Generally speaking magistrates, trade unionists, prefects, journalists and the police authorities expressed an affirmative judgement on the existence of more or less intimate links between Mafia and the public authorities … some trade unionists reached the point of saying that ‘the mafioso is a man of politics’.” The Commission’s main conclusion was that the Mafia was strong because it had penetrated the structure of the State.

The Commission was dissolved when new elections made an end to the legislature. In the next legislature, Cattanei was replaced with Luigi Carraro, a Christian Democrat that was more sensitive to the fears of the Christian Democrat Party that had been under attack of the Commission.

Disappointing results

Cesare Terranova

Cesare Terranova was a magistrate and politician from Sicily notable for his anti-Mafia stance. From 1958 until 1971 Terranova was an examining magistrate at the Palermo prosecuting office. He was one of the first to seriously investigate the Mafia and the financial operations of Cosa Nostra. He...

, previously chief investigative prosecutor in Palermo who had prepared several Mafia Trials in the 1960s, such as the Trial of the 114, that had ended with disappointing little convictions. He was elected for the Independent Left under the auspices of the Italian Communist Party

Italian Communist Party

The Italian Communist Party was a communist political party in Italy.The PCI was founded as Communist Party of Italy on 21 January 1921 in Livorno, by seceding from the Italian Socialist Party . Amadeo Bordiga and Antonio Gramsci led the split. Outlawed during the Fascist regime, the party played...

(PCI). He became the secretary of the Commission. Terranova, together with PCI deputy Pio La Torre

Pio La Torre

Pio La Torre was a leader of the Italian Communist Party...

, wrote the minority report of the Commission, which pointed to links between the Mafia

Mafia

The Mafia is a criminal syndicate that emerged in the mid-nineteenth century in Sicily, Italy. It is a loose association of criminal groups that share a common organizational structure and code of conduct, and whose common enterprise is protection racketeering...

and prominent politicians, in particular of the Christian Democrat party (DC - Democrazia Cristiana).

Terranova had urged his colleagues of the majority to take their responsibility. According to the minority report:

- … it would be a grave error on the part of the Commission to accept the theory that the Mafia-political link has been eliminated. Even today the behaviour of the ruling DC group in the running of the City and the Provincional Councils offers the most favourable terrain for the perpetuation of the system of Mafia power.

In the final report of the first Commission, the former mayor of Palermo

Palermo

Palermo is a city in Southern Italy, the capital of both the autonomous region of Sicily and the Province of Palermo. The city is noted for its history, culture, architecture and gastronomy, playing an important role throughout much of its existence; it is over 2,700 years old...

, Salvo Lima was described as one of the pillars of Mafia power in Palermo

Palermo

Palermo is a city in Southern Italy, the capital of both the autonomous region of Sicily and the Province of Palermo. The city is noted for its history, culture, architecture and gastronomy, playing an important role throughout much of its existence; it is over 2,700 years old...

. It had no formal consequences for Lima. (In 1993 the fourth Commission led by Luciano Violante

Luciano Violante

Luciano Violante is an Italian judge and politician, Member of Parliament since 1979. He is particularly interested in questions of justice, the struggle against the Mafia and institutional reform.-Biography:...

concluded that there were strong indications of relations between Lima and members of Cosa Nostra. By then Lima had been killed by the Mafia

Mafia

The Mafia is a criminal syndicate that emerged in the mid-nineteenth century in Sicily, Italy. It is a loose association of criminal groups that share a common organizational structure and code of conduct, and whose common enterprise is protection racketeering...

). In its conclusions, the Commission made many recommendations and offered much advice to those bodies that were going to take the job on. It criticized some authorities and condemned others. The government did nothing, however. When the results were published, every effort was made to confuse their message and diminish their value, and drowned in a sea of slander. The reports and the documentation of the Antimafia Commission were essentially disregarded. Terranova would talk of “thirteen wasted years” of the Antimafia Commission.

The final report was issued at a time when the question of the Mafia was pushed to the background by the political turmoil in the 1970s, known as the years of lead (it

Italian language

Italian is a Romance language spoken mainly in Europe: Italy, Switzerland, San Marino, Vatican City, by minorities in Malta, Monaco, Croatia, Slovenia, France, Libya, Eritrea, and Somalia, and by immigrant communities in the Americas and Australia...

: anni di piombo), a period characterized by widespread social conflicts and terrorism acts attributed to far-right and far-left political movements and the secret services.

The second Commission

Second Mafia War

The Second Mafia War was a conflict within the Sicilian Mafia, mostly taking place in the early 1980s. As with any criminal organization, the history of the Sicilian Mafia is replete with conflicts and power struggles, and the violence that results from them, but these are generally localised and...

, after the killing of former deputy and member of the first Antimafia Commission, Pio La Torre

Pio La Torre

Pio La Torre was a leader of the Italian Communist Party...

, on April 30, 1982, and the prefect of Palermo

Palermo

Palermo is a city in Southern Italy, the capital of both the autonomous region of Sicily and the Province of Palermo. The city is noted for its history, culture, architecture and gastronomy, playing an important role throughout much of its existence; it is over 2,700 years old...

, general Carlo Alberto Dalla Chiesa

Carlo Alberto Dalla Chiesa

Carlo Alberto Dalla Chiesa was a general of the Italian carabinieri notable for campaigning against terrorism during the 1970s in Italy, and later assassinated by the Mafia in Palermo.-Biography:...

on September 3, 1982. The first president was the Christian Democrat senator Nicola La Penta, who was succeeded by the Communist deputy Abdon Alinovi.

The Commission had no power to investigate. It analysed Antimafia legislation, in particular the new Antimafia law (known as the Rognoni-La Torre law) and the performance of the state and judicial authorities. While the Commission was in function, the Maxi Trial

Maxi Trial

The Maxi Trial was a criminal trial that took place in Sicily during the mid-1980s that saw hundreds of defendants on trial convicted for a multitude of crimes relating to Mafia activities, based primarily on testimony given in as evidence from a former boss turned informant...

against the Mafia took place in Palermo

Palermo

Palermo is a city in Southern Italy, the capital of both the autonomous region of Sicily and the Province of Palermo. The city is noted for its history, culture, architecture and gastronomy, playing an important role throughout much of its existence; it is over 2,700 years old...

. The Commission also analysed new developments in Cosa Nostra after their entry in drug trafficking. The Commission was dissolved at the end of the legislature in July 1987.

The third Commission

The third Commission was installed in March 1988 under the presidency of PCI senator Gerardo ChiaromonteGerardo Chiaromonte

Gerardo Chiaromonte was an Italian Communist politician, journalist and writer.-Biography:He was born in Naples into a poor family from Roccanova, a small village in the province of Potenza...

. This Commission marked a change in operations: the focus shifted from analyses and knowledge about the Mafia to proposals at the legislative and administrative level. The Commission studied the connections between the four Mafia-type organizations and the links between the Mafia and secret Masonic lodges. It lobbied for the introduction of new legislation such as the reform of the Rognoni-La Torre law whereby asset seizure and confiscation provisions were applicable to other forms of criminal association including drug trafficking, extortion

Extortion

Extortion is a criminal offence which occurs when a person unlawfully obtains either money, property or services from a person, entity, or institution, through coercion. Refraining from doing harm is sometimes euphemistically called protection. Extortion is commonly practiced by organized crime...

and usury

Usury

Usury Originally, when the charging of interest was still banned by Christian churches, usury simply meant the charging of interest at any rate . In countries where the charging of interest became acceptable, the term came to be used for interest above the rate allowed by law...

among others.

The third Commission decided to make public the 2.750 files on links between the Mafia and politicians that had been kept secret by the first Commission. Looking ahead to the general elections of April 5, 1992, in February 1992 the Commission urged political parties to apply a code of self-regulation when presenting candidates, a measure intended to mirror the legislative provisions for public-office holders in 1990: no one should stand for election who had been committed for trial, was a fugitive from the law, was serving a criminal sentence, was subject to preventive measures or was convicted, even though not definitively, for crimes of corruption, Mafia association and a range of others.

A week before the election the Commission reported that on the basis of information received from two-thirds of the prefectures in the country, 33 candidates standing in the forthcoming elections were ‘non presentable’ according to the code of self-regulation.

The fourth Commission

The fourth Commission was installed on June 8, 1992, after the murder of judge Giovanni FalconeGiovanni Falcone

Giovanni Falcone was an Sicilian/Italian prosecuting magistrate born in Palermo, Sicily. From his office in the Palace of Justice in Palermo, he spent most of his professional life trying to overthrow the power of the Mafia in Sicily...

on May 23 and was modified after the killing of his colleague Paolo Borsellino

Paolo Borsellino

Paolo Borsellino was an Italian anti-Mafia magistrate who was killed by a Mafia car bomb in Palermo, less than two months after his fellow anti-Mafia magistrate Giovanni Falcone had been assassinated....

on July 19. On September 23, Luciano Violante

Luciano Violante

Luciano Violante is an Italian judge and politician, Member of Parliament since 1979. He is particularly interested in questions of justice, the struggle against the Mafia and institutional reform.-Biography:...

from the Democratic Party of the Left

Democratic Party of the Left

The Democratic Party of the Left was a post-communist, democratic socialist political party in Italy.-History:...

(Partito democratico della Sinistra, PDS) was appointed president of the Commission. Under Violante’s leadership the Commission worked for 17 months until the dissolution of Parliament in February 1994. It passed 13 reports, but its most important one was on the relations between the Mafia

Mafia

The Mafia is a criminal syndicate that emerged in the mid-nineteenth century in Sicily, Italy. It is a loose association of criminal groups that share a common organizational structure and code of conduct, and whose common enterprise is protection racketeering...

and politics, the so-called terzo livello (third level) of the Mafia

Mafia

The Mafia is a criminal syndicate that emerged in the mid-nineteenth century in Sicily, Italy. It is a loose association of criminal groups that share a common organizational structure and code of conduct, and whose common enterprise is protection racketeering...

, on April 6, 1993.

The Commission had to work in one of Italy’s most critical moment when the country’s democracy was challenged by criminal subversion by the Mafia and the Mani pulite

Mani pulite

Mani pulite was a nationwide Italian judicial investigation into political corruption held in the 1990s. Mani pulite led to the demise of the so-called First Republic, resulting in the disappearance of many parties. Some politicians and industry leaders committed suicide after their crimes were...

investigation that unravelled Tangentopoli

Tangentopoli

Tangentopoli is a term which was coined to describe pervasive corruption in the Italian political system exposed in the 1992-6 Mani Pulite investigations, as well as the resulting scandal, which led to the collapse of the hitherto dominant Christian Democracy party and its allies.-Popular distrust...

(Italian

Italian language

Italian is a Romance language spoken mainly in Europe: Italy, Switzerland, San Marino, Vatican City, by minorities in Malta, Monaco, Croatia, Slovenia, France, Libya, Eritrea, and Somalia, and by immigrant communities in the Americas and Australia...

for bribeville), the corruption

Political corruption

Political corruption is the use of legislated powers by government officials for illegitimate private gain. Misuse of government power for other purposes, such as repression of political opponents and general police brutality, is not considered political corruption. Neither are illegal acts by...

-based political system that dominated Italy

Italy

Italy , officially the Italian Republic languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Italy's official name is as follows:;;;;;;;;), is a unitary parliamentary republic in South-Central Europe. To the north it borders France, Switzerland, Austria and...

. Despite the political sensitive nature of the Commission’s work, Violante’s greatest achievement was that the most important reports were backed by all major parties instead, as in the past, of producing majority (government) and minority (opposition) reports on the same theme.

Important pentiti

Pentito

Pentito designates people in Italy who, formerly part of criminal or terrorist organizations, following their arrests decide to "repent" and collaborate with the judicial system to help investigations...

like Tommaso Buscetta

Tommaso Buscetta

Tommaso Buscetta was a Sicilian mafioso. Although he was not the first pentito in the Italian witness protection program, he is widely recognized as the first important one breaking omertà...

, Antonio Calderone, Leonardo Messina

Leonardo Messina

Leonardo "Narduzzo" Messina is a former Sicilian mafioso who became a government informant or "pentito" in 1992. His testimony led to the arrest of over 200 mafiosi during the so-called "Operation Leopard"...

and Gaspare Mutolo

Gaspare Mutolo

Gaspare Mutolo is a Sicilian mafioso, also known as "Asparino". In 1992 he became a pentito . He was the first mafioso who spoke about the connections between Cosa Nostra and Italian politicians...

gave testimonies. It found that Salvo Lima, a former Christian Democrat

Christian Democracy (Italy)

Christian Democracy was a Christian democratic party in Italy. It was founded in 1943 as the ideological successor of the historical Italian People's Party, which had the same symbol, a crossed shield ....

mayor of Palermo

Palermo

Palermo is a city in Southern Italy, the capital of both the autonomous region of Sicily and the Province of Palermo. The city is noted for its history, culture, architecture and gastronomy, playing an important role throughout much of its existence; it is over 2,700 years old...

who was murdered in March 1992, had been linked to the Mafia and that former Prime Minister Giulio Andreotti

Giulio Andreotti

Giulio Andreotti is an Italian politician of the now dissolved centrist Christian Democracy party. He served as the 42nd Prime Minister of Italy from 1972 to 1973, from 1976 to 1979 and from 1989 to 1992. He also served as Minister of the Interior , Defense Minister and Foreign Minister and he...

had been Lima's "political contact" in Rome. On November 16, 1992 Tommaso Buscetta

Tommaso Buscetta

Tommaso Buscetta was a Sicilian mafioso. Although he was not the first pentito in the Italian witness protection program, he is widely recognized as the first important one breaking omertà...

testified before the Antimafia Commission. "Salvo Lima was, in fact, the politician to whom Cosa Nostra turned most often to resolve problems for the organisation whose solution lay in Rome," Buscetta said. Other collaborating witnesses confirmed that Lima had been specifically ordered to "fix" the appeal of the Maxi Trial

Maxi Trial

The Maxi Trial was a criminal trial that took place in Sicily during the mid-1980s that saw hundreds of defendants on trial convicted for a multitude of crimes relating to Mafia activities, based primarily on testimony given in as evidence from a former boss turned informant...

with Italy's Supreme Court and had been murdered because he failed to do so.

Gaspare Mutolo

Gaspare Mutolo

Gaspare Mutolo is a Sicilian mafioso, also known as "Asparino". In 1992 he became a pentito . He was the first mafioso who spoke about the connections between Cosa Nostra and Italian politicians...

warned the Commission in February 1993 of the likelihood that further attacks were being planned by the Corleonesi

Corleonesi

The Corleonesi is the name given to a faction within the Sicilian Mafia that dominated Cosa Nostra in the 1980s and the 1990s. It was called the Corleonesi because its most important leaders came from the town of Corleone, first Luciano Leggio and later Totò Riina, Bernardo Provenzano and Leoluca...

on the mainland.

The Senate authorized to proceed with the criminal investigation of Giulio Andreotti

Giulio Andreotti

Giulio Andreotti is an Italian politician of the now dissolved centrist Christian Democracy party. He served as the 42nd Prime Minister of Italy from 1972 to 1973, from 1976 to 1979 and from 1989 to 1992. He also served as Minister of the Interior , Defense Minister and Foreign Minister and he...

on June 10, 1993 (he was formally committed for trial in Palermo on March 2, 1995).

The other Commissions

After Violante, presidents of the Commission were Tiziana Parenti, from Forza ItaliaForza Italia

Forza Italia was a liberal-conservative, Christian democratic, and liberal political party in Italy, with a large social democratic minority, that was led by Silvio Berlusconi, four times Prime Minister of Italy....

(1994–1996), Ottaviano Del Turco

Ottaviano Del Turco

Ottaviano Del Turco is an Italian politician. After a career in trade unionism in the Italian General Confederation of Labour Del Turco rose to the top of Bettino Craxi's Italian Socialist Party before it was swept away in the Tangentopoli scandals of 1992-94.Del Turco was the president of the...

, from the Italian Democratic Socialists

Italian Democratic Socialists

The Italian Democratic Socialists were a small social-democratic political party in Italy. Led by Enrico Boselli, the party was the direct continuation of the Italian Socialists, the legal successor of the historical Italian Socialist Party...

(1996–1999), Giuseppe Lumia

Giuseppe Lumia

Giuseppe Lumia is an Italian politician of the Democratic Party of the Left and its successor, the Democrats of the Left . He belongs to the group of Social Christians in the Party.Lumia was born in Termini Imerese, in Sicily...

, from the Democratic Left

Democratic Left

Democratic Left, Democratic Left Party, or Party of the Democratic Left may refer to:-Political parties:*Democratic Left *Democratic Left *Democratic Left *Democratic Left *Democratic Left...

(2000–2001), Roberto Centaro from Forza Italia

Forza Italia

Forza Italia was a liberal-conservative, Christian democratic, and liberal political party in Italy, with a large social democratic minority, that was led by Silvio Berlusconi, four times Prime Minister of Italy....

(2001–2006), Francesco Forgione

Francesco Forgione

Francesco Forgione may refer to:*Pio of Pietrelcina, Italian priest, popularly known as Padre Pio*Francesco Forgione , Italian politician of the Communist Refoundation Party, president of the Antimafia Commission, 2006–2008...

from the Communist Refoundation Party

Communist Refoundation Party

The Communist Refoundation Party is a communist Italian political party. Its current secretary is Paolo Ferrero....

(2006–2008). Currently the president is Giuseppe Pisanu

Giuseppe Pisanu

Giuseppe Pisanu is an Italian politician, longtime member of the Chamber of Deputies for the Christian Democracy and then for Forza Italia...

.