William Webb Ellis

Encyclopedia

Rev. William Webb Ellis (24 November 1806 – 24 February 1872) was an Anglican clergyman who is famous for allegedly being the inventor of Rugby football

Rugby football

Rugby football is a style of football named after Rugby School in the United Kingdom. It is seen most prominently in two current sports, rugby league and rugby union.-History:...

whilst a pupil at Rugby School

Rugby School

Rugby School is a co-educational day and boarding school located in the town of Rugby, Warwickshire, England. It is one of the oldest independent schools in Britain.-History:...

.

Web Ellis's name is firmly established in rugby union

Rugby union

Rugby union, often simply referred to as rugby, is a full contact team sport which originated in England in the early 19th century. One of the two codes of rugby football, it is based on running with the ball in hand...

folklore and the William Webb Ellis Cup is presented to the winners of the Rugby World Cup

Rugby World Cup

The Rugby World Cup is an international rugby union competition organised by the International Rugby Board and held every four years since 1987....

.

Biography

Lancashire

Lancashire is a non-metropolitan county of historic origin in the North West of England. It takes its name from the city of Lancaster, and is sometimes known as the County of Lancaster. Although Lancaster is still considered to be the county town, Lancashire County Council is based in Preston...

(some sources say he was born in Manchester

Manchester

Manchester is a city and metropolitan borough in Greater Manchester, England. According to the Office for National Statistics, the 2010 mid-year population estimate for Manchester was 498,800. Manchester lies within one of the UK's largest metropolitan areas, the metropolitan county of Greater...

as Webb Ellis himself said he was born there in the 1851 census as he later moved to the city). He was the younger of two sons of James Ellis, an officer in the Dragoon Guards

Dragoon guards

Dragoon Guards was the designation used to refer to certain heavy cavalry regiments in the British Army from the 18th century onwards. While the Prussian and Russian armies of the same period included dragoon regiments amongst their respective Imperial Guards, different titles were applied to these...

, and Ann Webb, whom James married in Exeter

Exeter

Exeter is a historic city in Devon, England. It lies within the ceremonial county of Devon, of which it is the county town as well as the home of Devon County Council. Currently the administrative area has the status of a non-metropolitan district, and is therefore under the administration of the...

in 1804. After his father was killed at the Battle of Albuera

Battle of Albuera

The Battle of Albuera was an indecisive battle during the Peninsular War. A mixed British, Spanish and Portuguese corps engaged elements of the French Armée du Midi at the small Spanish village of Albuera, about 20 kilometres south of the frontier fortress-town of Badajoz, Spain.From...

in 1811, Mrs Ellis decided to move to Rugby, Warwickshire

Rugby, Warwickshire

Rugby is a market town in Warwickshire, England, located on the River Avon. The town has a population of 61,988 making it the second largest town in the county...

so that William and his older brother Thomas could receive an education at Rugby School

Rugby School

Rugby School is a co-educational day and boarding school located in the town of Rugby, Warwickshire, England. It is one of the oldest independent schools in Britain.-History:...

with no cost as a local foundationer (i.e. a pupil living within a radius of 10 miles of the Rugby Clock Tower). He attended the school from 1816 to 1825 and was recorded as being a good scholar and cricket

Cricket

Cricket is a bat-and-ball game played between two teams of 11 players on an oval-shaped field, at the centre of which is a rectangular 22-yard long pitch. One team bats, trying to score as many runs as possible while the other team bowls and fields, trying to dismiss the batsmen and thus limit the...

er, although it was noted that he was 'rather inclined to take unfair advantage at cricket'. The incident in which Webb Ellis supposedly caught the ball in his arms during a football match (which was allowed) and ran with it (which was not) meant to have happened in the latter half of 1823.

After leaving Rugby in 1826, he went to Brasenose College, Oxford

Brasenose College, Oxford

Brasenose College, originally Brazen Nose College , is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom. As of 2006, it has an estimated financial endowment of £98m...

aged 18. He played cricket

Cricket

Cricket is a bat-and-ball game played between two teams of 11 players on an oval-shaped field, at the centre of which is a rectangular 22-yard long pitch. One team bats, trying to score as many runs as possible while the other team bowls and fields, trying to dismiss the batsmen and thus limit the...

for his college, and for Oxford University against Cambridge University in 1827. He graduated with a BA in 1829 and received his MA in 1831. He entered the Church

Church of England

The Church of England is the officially established Christian church in England and the Mother Church of the worldwide Anglican Communion. The church considers itself within the tradition of Western Christianity and dates its formal establishment principally to the mission to England by St...

and became chaplain of St George's, Albemarle Street

Albemarle Street

Albemarle Street is a street in Mayfair in central London, off Piccadilly. It has historic associations with Lord Byron, whose publisher John Murray was based here, and Oscar Wilde, a member of the Albemarle Club, where an insult he received led to his suing for libel and to his eventual imprisonment...

, London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

and then rector

Rector

The word rector has a number of different meanings; it is widely used to refer to an academic, religious or political administrator...

of St. Clement Danes in The Strand

Strand, London

Strand is a street in the City of Westminster, London, England. The street is just over three-quarters of a mile long. It currently starts at Trafalgar Square and runs east to join Fleet Street at Temple Bar, which marks the boundary of the City of London at this point, though its historical length...

. He became well known as a low church

Low church

Low church is a term of distinction in the Church of England or other Anglican churches initially designed to be pejorative. During the series of doctrinal and ecclesiastic challenges to the established church in the 16th and 17th centuries, commentators and others began to refer to those groups...

evangelical

Evangelism

Evangelism refers to the practice of relaying information about a particular set of beliefs to others who do not hold those beliefs. The term is often used in reference to Christianity....

clergyman. In 1855, he became rector of Magdalen Laver

Magdalen Laver

Magdalen Laver is a village and a civil parish in the Epping Forest district, in the county of Essex, England. Magdalen Laver has a village hall and a church called St Mary Magdalen.- External links :*...

in Essex

Essex

Essex is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in the East region of England, and one of the home counties. It is located to the northeast of Greater London. It borders with Cambridgeshire and Suffolk to the north, Hertfordshire to the west, Kent to the South and London to the south west...

. A picture of him (the only known portrait) appeared in the Illustrated London News

Illustrated London News

The Illustrated London News was the world's first illustrated weekly newspaper; the first issue appeared on Saturday 14 May 1842. It was published weekly until 1971 and then increasingly less frequently until publication ceased in 2003.-History:...

in 1854, after he gave a particularly stirring sermon on the subject of the Crimean War

Crimean War

The Crimean War was a conflict fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the French Empire, the British Empire, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Sardinia. The war was part of a long-running contest between the major European powers for influence over territories of the declining...

.

He never married and died in the south of France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

in 1872, leaving an estate of £9,000, mostly to various charities. His grave in "le cimetière du vieux château" at Menton

Menton

Menton is a commune in the Alpes-Maritimes department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region in southeastern France.Situated on the French Riviera, along the Franco-Italian border, it is nicknamed la perle de la France ....

in Alpes Maritimes was rediscovered by Ross McWhirter

Ross McWhirter

Alan Ross Mayfield McWhirter , known as Ross McWhirter, was, with his twin brother, Norris McWhirter, co-founder of the Guinness Book of Records and a contributor to Record Breakers...

in 1958 and has since been renovated by the French Rugby Federation.

Origin of the claim

The sole source of the story of Webb Ellis picking up the ball originates with one Matthew BloxamMatthew Bloxam

Matthew Holbeche Bloxam , a native of Rugby, Warwickshire, England, was an amateur archeologist and Warwickshire antiquary. He was the original source of the legend of William Webb Ellis inventing the game of Rugby football....

, a local antiquarian and former pupil of Rugby. On 10 October 1876, he wrote to The Meteor, the Rugby School magazine, that he had learnt from an unnamed source that the change from a kicking game to a handling game had "...originated with a town boy or foundationer of the name of Ellis, Webb Ellis".

On 22 December 1880, in another letter to the Meteor, Bloxam elaborates on the story:

- "A boy of the name Ellis – William Webb Ellis – a town boy and a foundationer, ... whilst playing Bigside at football in that half-year [1823], caught the ball in his arms. This being so, according to the then rules, he ought to have retired back as far as he pleased, without parting with the ball, for the combatants on the opposite side could only advance to the spot where he had caught the ball, and were unable to rush forward till he had either punted it or had placed it for some one else to kick, for it was by means of these placed kicks that most of the goals were in those days kicked, but the moment the ball touched the ground the opposite side might rush on. Ellis, for the first time, disregarded this rule, and on catching the ball, instead of retiring backwards, rushed forwards with the ball in his hands towards the opposite goal, with what result as to the game I know not, neither do I know how this infringement of a well-known rule was followed up, or when it became, as it is now, a standing rule."

Bloxham's first account differed from his second one four years later. In his first letter, in 1876, Bloxham claimed that Webb Ellis committed the act in 1824, a time by which Webb Ellis had left Rugby. In his second letter, in 1880, Bloxham put the year as 1823.

1895 investigation

The claim that Webb Ellis invented the game did not surface until four years after his death and doubts have been raised about the story since 1895 when it was first investigated by the Old Rugbeian Society. The sub-committee conducting the investigation was "unable to procure any first hand evidence of the occurrence".Among those giving evidence, Thomas Harris and his brother John, who had left Rugby in 1828 and 1832 respectively (i.e. after the alleged Webb Ellis incident) recalled that handling of the ball was strictly forbidden. Harris, who requested that he "not [be] quote[d] as an authority", testified that Webb Ellis had been known as someone to take an "unfair advantage at football". Harris, who would have been aged 10 years at the time of the alleged incident, did not claim to have been a witness to it, additionally, he stated that he had not heard the story of Webb Ellis' creation of the game.

Thomas Hughes

Thomas Hughes

Thomas Hughes was an English lawyer and author. He is most famous for his novel Tom Brown's Schooldays , a semi-autobiographical work set at Rugby School, which Hughes had attended. It had a lesser-known sequel, Tom Brown at Oxford .- Biography :Hughes was the second son of John Hughes, editor of...

(author of Tom Brown's Schooldays

Tom Brown's Schooldays

Tom Brown's Schooldays is a novel by Thomas Hughes. The story is set at Rugby School, a public school for boys, in the 1830s; Hughes attended Rugby School from 1834 to 1842...

) was asked to comment on the game as played when he attended the school (1834–1842). He is quoted as saying "In my first year, 1834, running with the ball to get a try by touching down within goal was not absolutely forbidden, but a jury of Rugby boys of that day would almost certainly have found a verdict of 'justifiable homicide' if a boy had been killed in running in."

It has been suggested by Dunning and Sheard (2005) that it was no coincidence that this investigation was conducted in 1895, at a time when divisions within the sport led to the schism; the split into the sports of league

Rugby league

Rugby league football, usually called rugby league, is a full contact sport played by two teams of thirteen players on a rectangular grass field. One of the two codes of rugby football, it originated in England in 1895 by a split from Rugby Football Union over paying players...

and union

Rugby union

Rugby union, often simply referred to as rugby, is a full contact team sport which originated in England in the early 19th century. One of the two codes of rugby football, it is based on running with the ball in hand...

. Dunning and Sheard suggest that the endorsement of a "reductionist" origin myth

Origin myth

An origin myth is a myth that purports to describe the origin of some feature of the natural or social world. One type of origin myth is the cosmogonic myth, which describes the creation of the world...

by the Rugbeians was an attempt to assert their school's position and authority over a sport that they were losing control of.

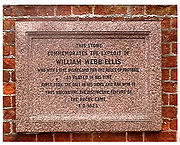

The plaque

A plaque, erected in 1895, at Rugby School bears the inscription:THIS STONE COMMEMORATES THE EXPLOIT OF WILLIAM WEBB ELLIS WHO WITH A FINE DISREGARD FOR THE RULES OF FOOTBALL AS PLAYED IN HIS TIME FIRST TOOK THE BALL IN HIS ARMS AND RAN WITH IT THUS ORIGINATING THE DISTINCTIVE FEATURE OF THE RUGBY GAME A.D. 1823 |  |

Controversy

A number of codes of mediaeval football allowed the carrying of the ball, as indeed do several other current football codes.Some sources have claimed that Ellis may have actually been giving a demonstration of a sport known as caid

Caid (sport)

Caid is the name given to various ancient and traditional Irish football games. "Caid" is now used by people in some parts of Ireland to refer to modern Gaelic football.The word caid originally referred to the ball which was used...

, which was an ancient Irish game that is similar to rugby, and is the ancestor of Gaelic football

Gaelic football

Gaelic football , commonly referred to as "football" or "Gaelic", or "Gah" is a form of football played mainly in Ireland...

. Some speculate that Ellis could have witnessed it during his youth whilst his soldier father was stationed in Ireland. Though this story, as dubious as it may be, adds fuel to the speculation that Ellis did not create the game per se, as there had previously been sports such as caid and harpastum

Harpastum

Harpastum, also known as Harpustum, was a form of ball game played in the Roman Empire. The Romans also referred to it as the small ball game. The ball used was small and hard, probably about the size and solidity of a softball...

, a game which was similar to rugby that was played by the ancient Romans. There was another game in Wales called "cnapan

Cnapan

Cnapan is a Celtic form of medieval football, vaguely resembling some modern versions of rugby football, played in Wales until the nineteenth century. It may be a forerunner to modern rugby union...

", which was still being played in 1823. That involved teams of up to 1,000 players on each side, and it was a running, handling and passing game with much physical contact and with elements that resembled scrums and lineouts. There was no kicking of the ball in that game, since it was made of wood and (to add interest) boiled in tallow to make it slippery! Could some of the boys at Rugby School have known about that game?

There is also much speculation as to what kind of rules were in place for football at the Rugby School. Some sources have claimed that the rules of the game being played were constantly altered. Malcom Lee said in an interview that "...the rules were discussed almost every time the boys went out to play and that adjustments were frequently made [to the game]" http://www.pshortell.demon.co.uk/rugby/wwe.htm

It is clear that the drop-goal was an integral part of the game at that time - indeed it was the major way of scoring a goal. The rules required a player to catch the ball cleanly and at the same time make a mark with his heel. That entitled him to a "free kick" i.e. free of interference by the opposition. They were allowed to line up on the mark, but not charge until the player offered to kick. If a player were running to catch the ball, what more natural than that he should continue his run after the catch (despite the need to dig in his heel)? There is little reason to believe that Ellis would have been the only, or even the first, player to do this.

General

- K. G. Sheard, "Ellis, William Webb (1806–1872)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University PressOxford University PressOxford University Press is the largest university press in the world. It is a department of the University of Oxford and is governed by a group of 15 academics appointed by the Vice-Chancellor known as the Delegates of the Press. They are headed by the Secretary to the Delegates, who serves as...

, Sept 2004; online edn, Oct 2006 accessed 23 October 2007