Theodore William Richards

Encyclopedia

Theodore William Richards (January 31, 1868 – April 2, 1928) was the first American

scientist

to receive the Nobel Prize in Chemistry

, earning the award "in recognition of his exact determinations of the atomic weight

s of a large number of the chemical element

s."

to William Trost Richards

, a land- and seascape painter, and Anna née Matlack, a poet. Richards received most of his pre-college education from his mother. During one summer's stay at Newport, Rhode Island

, Richards met Professor Josiah Parsons Cooke

of Harvard, who showed the young boy Saturn's rings through a small telescope. Years later Cooke and Richards would work together in Cooke's laboratory.

Beginning in 1878, the Richards family spent two years in Europe, largely in England, where Theodore Richards' scientific interests grew stronger. After the family's return to the United States, he entered Haverford College

, Pennsylvania in 1883 at the age of 14, earning a Bachelor of Science degree in 1885. He then enrolled at Harvard University

and received a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1886, as further preparation for graduate studies.

Richards continued on at Harvard, obtaining a Ph.D.

in chemistry in 1888 for a determination of the atomic weight of oxygen relative to hydrogen. His doctoral advisor was Josiah Parsons Cooke. Following a year of post-doctoral work in Germany

, where he studied under Victor Meyer and others, Richards returned to Harvard as an assistant in chemistry, then instructor, assistant professor, and finally full professor in 1901. In 1903 he became chairman of the Department of Chemistry at Harvard, and in 1912 he was appointed Erving Professor of Chemistry and Director of the new Wolcott Gibbs Memorial Laboratory.

In 1896, Richards married Miriam Stuart Thayer. The couple had one daughter, Grace Thayer (who married James Bryant Conant

), and two sons, Greenough Thayer and William Theodore. Both sons died by suicide.

Richards' maintained interests in both art and music. Among his recreations were sketching, golf, and sailing. He died at Cambridge, Massachusetts, on April 2, 1928, at the age of 60. According to one of his descendants, Richards suffered from "chronic respiratory problems and a prolonged depression."

He was a Quaker

.

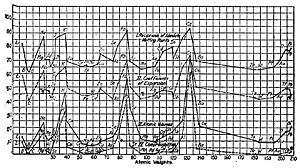

About half of Richards's scientific research concerned atomic weight

About half of Richards's scientific research concerned atomic weight

s, starting in 1886 with his graduate studies. On returning to Harvard in 1889, this was his first line of research, continuing up to his death. According to Forbes, by 1932 the atomic weights of 55 elements had been studied by Richards and his students. Among the potential sources of error Richards uncovered in such determinations was the tendency of certain salts to occlude gases or foreign solutes on precipitation. As an example of the care Richards used in his work, Emsley reports that he carried out 15,000 recrystallization of thulium bromate in order to obtain the pure element thulium for an atomic weight measurement.

Richards was the first to show, by chemical analysis, that an element could have different atomic weights. He was asked to analyze samples of naturally-occurring lead and lead produced by radioactive decay. His measurements showed that the two samples had different atomic weights, supporting the concepts of isotopes.

Although Richards's chemical determinations of atomic weights were highly significant for their time, they have largely been superseded. Modern scientists use electronic instrumentation, such as mass spectrometers, to determine both the masses and the abundances of an element's isotopes. From this information, an average atomic mass can be calculated, and compared to the values measured by Richards. The modern methods are faster and more sensitive than those on which Richards had to rely, but not necessarily less expensive.

Other scientific work of Theodore Richards included investigations of the compressibilities of atoms, heats of solution and neutralization, and the electrochemistry of amalgams. His investigation of electrochemical potentials at low temperatures was among the work that led, in the hands of others, to the Nernst heat theorem

and the third law of thermodynamics, although not without heated debate between Nernst and Richards.

Richards also is credited with the invention of the adiabatic calorimeter

as well as the nephelometer

, which was devised for his work on the atomic weight of strontium.

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

scientist

Scientist

A scientist in a broad sense is one engaging in a systematic activity to acquire knowledge. In a more restricted sense, a scientist is an individual who uses the scientific method. The person may be an expert in one or more areas of science. This article focuses on the more restricted use of the word...

to receive the Nobel Prize in Chemistry

Nobel Prize in Chemistry

The Nobel Prize in Chemistry is awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences to scientists in the various fields of chemistry. It is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Alfred Nobel in 1895, awarded for outstanding contributions in chemistry, physics, literature,...

, earning the award "in recognition of his exact determinations of the atomic weight

Atomic weight

Atomic weight is a dimensionless physical quantity, the ratio of the average mass of atoms of an element to 1/12 of the mass of an atom of carbon-12...

s of a large number of the chemical element

Chemical element

A chemical element is a pure chemical substance consisting of one type of atom distinguished by its atomic number, which is the number of protons in its nucleus. Familiar examples of elements include carbon, oxygen, aluminum, iron, copper, gold, mercury, and lead.As of November 2011, 118 elements...

s."

Biography

Theodore Richards was born in Germantown, Philadelphia, PennsylvaniaGermantown, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Germantown is a neighborhood in the northwest section of the city of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States, about 7–8 miles northwest from the center of the city...

to William Trost Richards

William Trost Richards

William Trost Richards was an American landscape artist associated with both the Hudson River School and the American Pre-Raphaelite movement.-Biography:...

, a land- and seascape painter, and Anna née Matlack, a poet. Richards received most of his pre-college education from his mother. During one summer's stay at Newport, Rhode Island

Newport, Rhode Island

Newport is a city on Aquidneck Island in Newport County, Rhode Island, United States, about south of Providence. Known as a New England summer resort and for the famous Newport Mansions, it is the home of Salve Regina University and Naval Station Newport which houses the United States Naval War...

, Richards met Professor Josiah Parsons Cooke

Josiah Parsons Cooke

Josiah Parsons Cooke was an American scientist who worked at Harvard University and was instrumental in the measurement of atomic weights, inspiring America's first Nobel laureate in chemistry, Theodore Richards, to pursue similar research...

of Harvard, who showed the young boy Saturn's rings through a small telescope. Years later Cooke and Richards would work together in Cooke's laboratory.

Beginning in 1878, the Richards family spent two years in Europe, largely in England, where Theodore Richards' scientific interests grew stronger. After the family's return to the United States, he entered Haverford College

Haverford College

Haverford College is a private, coeducational liberal arts college located in Haverford, Pennsylvania, United States, a suburb of Philadelphia...

, Pennsylvania in 1883 at the age of 14, earning a Bachelor of Science degree in 1885. He then enrolled at Harvard University

Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League university located in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States, established in 1636 by the Massachusetts legislature. Harvard is the oldest institution of higher learning in the United States and the first corporation chartered in the country...

and received a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1886, as further preparation for graduate studies.

Richards continued on at Harvard, obtaining a Ph.D.

Doctor of Philosophy

Doctor of Philosophy, abbreviated as Ph.D., PhD, D.Phil., or DPhil , in English-speaking countries, is a postgraduate academic degree awarded by universities...

in chemistry in 1888 for a determination of the atomic weight of oxygen relative to hydrogen. His doctoral advisor was Josiah Parsons Cooke. Following a year of post-doctoral work in Germany

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

, where he studied under Victor Meyer and others, Richards returned to Harvard as an assistant in chemistry, then instructor, assistant professor, and finally full professor in 1901. In 1903 he became chairman of the Department of Chemistry at Harvard, and in 1912 he was appointed Erving Professor of Chemistry and Director of the new Wolcott Gibbs Memorial Laboratory.

In 1896, Richards married Miriam Stuart Thayer. The couple had one daughter, Grace Thayer (who married James Bryant Conant

James Bryant Conant

James Bryant Conant was a chemist, educational administrator, and government official. As thePresident of Harvard University he reformed it as a research institution.-Biography :...

), and two sons, Greenough Thayer and William Theodore. Both sons died by suicide.

Richards' maintained interests in both art and music. Among his recreations were sketching, golf, and sailing. He died at Cambridge, Massachusetts, on April 2, 1928, at the age of 60. According to one of his descendants, Richards suffered from "chronic respiratory problems and a prolonged depression."

He was a Quaker

Religious Society of Friends

The Religious Society of Friends, or Friends Church, is a Christian movement which stresses the doctrine of the priesthood of all believers. Members are known as Friends, or popularly as Quakers. It is made of independent organisations, which have split from one another due to doctrinal differences...

.

Scientific research

Atomic weight

Atomic weight is a dimensionless physical quantity, the ratio of the average mass of atoms of an element to 1/12 of the mass of an atom of carbon-12...

s, starting in 1886 with his graduate studies. On returning to Harvard in 1889, this was his first line of research, continuing up to his death. According to Forbes, by 1932 the atomic weights of 55 elements had been studied by Richards and his students. Among the potential sources of error Richards uncovered in such determinations was the tendency of certain salts to occlude gases or foreign solutes on precipitation. As an example of the care Richards used in his work, Emsley reports that he carried out 15,000 recrystallization of thulium bromate in order to obtain the pure element thulium for an atomic weight measurement.

Richards was the first to show, by chemical analysis, that an element could have different atomic weights. He was asked to analyze samples of naturally-occurring lead and lead produced by radioactive decay. His measurements showed that the two samples had different atomic weights, supporting the concepts of isotopes.

Although Richards's chemical determinations of atomic weights were highly significant for their time, they have largely been superseded. Modern scientists use electronic instrumentation, such as mass spectrometers, to determine both the masses and the abundances of an element's isotopes. From this information, an average atomic mass can be calculated, and compared to the values measured by Richards. The modern methods are faster and more sensitive than those on which Richards had to rely, but not necessarily less expensive.

Other scientific work of Theodore Richards included investigations of the compressibilities of atoms, heats of solution and neutralization, and the electrochemistry of amalgams. His investigation of electrochemical potentials at low temperatures was among the work that led, in the hands of others, to the Nernst heat theorem

Nernst heat theorem

The Nernst heat theorem was formulated by Walther Nernst early in the twentieth century and was used in the development of the third law of thermodynamics.- The theorem :...

and the third law of thermodynamics, although not without heated debate between Nernst and Richards.

Richards also is credited with the invention of the adiabatic calorimeter

Calorimeter

A calorimeter is a device used for calorimetry, the science of measuring the heat of chemical reactions or physical changes as well as heat capacity. Differential scanning calorimeters, isothermal microcalorimeters, titration calorimeters and accelerated rate calorimeters are among the most common...

as well as the nephelometer

Nephelometer

A nephelometer is a stationary or portable instrument for measuring suspended particulates in a liquid or gas colloid. A nephelometer measures suspended particulates by employing a light beam and a light detector set to one side of the source beam. Particle density is then a function of the...

, which was devised for his work on the atomic weight of strontium.

Legacy and honors

- Lowell Lectures (1908)

- Davy MedalDavy MedalThe Davy Medal is awarded by the Royal Society of London "for an outstandingly important recent discovery in any branch of chemistry". Named after Humphry Davy, the medal is awarded with a gift of £1000. The medal was first awarded in 1877 to Robert Wilhelm Bunsen and Gustav Robert Kirchhoff "for...

(1910) - Faraday Medal (1911)

- Willard Gibbs Medal (1912)

- President of the American Chemical SocietyAmerican Chemical SocietyThe American Chemical Society is a scientific society based in the United States that supports scientific inquiry in the field of chemistry. Founded in 1876 at New York University, the ACS currently has more than 161,000 members at all degree-levels and in all fields of chemistry, chemical...

(1914) - Nobel Prize in Chemistry (1914)

- Franklin MedalFranklin MedalThe Franklin Medal was a science and engineering award presented by the Franklin Institute, of Philadelphia, PA, USA.-Laureates:*1915 - Thomas Alva Edison *1915 - Heike Kamerlingh Onnes *1916 - John J...

(1916) - President of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (1917)

- President of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences President (1919 – 1921)

- Lavoisier Medal (1922)

- Le Blanc Medal (1922)

- Theodore Richards Medal (1932, awarded posthumously)

See also

- Mass spectrometryMass spectrometryMass spectrometry is an analytical technique that measures the mass-to-charge ratio of charged particles.It is used for determining masses of particles, for determining the elemental composition of a sample or molecule, and for elucidating the chemical structures of molecules, such as peptides and...

- Jöns Jakob BerzeliusJöns Jakob BerzeliusJöns Jacob Berzelius was a Swedish chemist. He worked out the modern technique of chemical formula notation, and is together with John Dalton, Antoine Lavoisier, and Robert Boyle considered a father of modern chemistry...

- Farrington DanielsFarrington DanielsFarrington Daniels , was an American physical chemist, is considered one of the pioneers of the modern direct use of solar energy.- Biography :Daniels was born in Minneapolis, Minnesota on March 8, 1889...

- Gilbert Newton Lewis

- Jean StasJean StasJean Servais Stas was a Belgian analytical chemist.- Life and work :Stas was born in Leuven and trained initially as a physician. He later switched to chemistry and worked at the École Polytechnique in Paris under the direction of Jean-Baptiste Dumas...

- Theodore W. Richards HouseTheodore W. Richards HouseThe Theodore W. Richards House is a National Historic Landmark at 15 Follen Street in Cambridge, Massachusetts.The house was built in 1900 by Warren, Smith & Biscoe and was the home of Harvard University chemist and 1914 Nobel Prize winner, Theodore William Richards. The house was added to the...