Social determinants of health

Encyclopedia

Social determinants of health are the economic and social conditions under which people live which determine their health

. They are "societal risk conditions", rather than individual risk factor

s that either increase or decrease the risk for a disease

, for example for cardiovascular disease

and type II diabetes.

A succinct statement of what they are and why they are important can be found at http://thecanadianfacts.org

As stated in Social Determinants of Health: The Solid Facts (WHO, 2003):

"Health policy was once thought to be about little more than the provision and funding of medical care: the social determinants of health were discussed only among academics. This is now changing. While medical care can prolong survival and improve prognosis after some serious diseases, more important for the health of the population as a whole are the social and economic conditions that make people ill and in need of medical care in the first place. Nevertheless, universal access to medical care is clearly one of the social determinants of health."

Raphael (2008) reinforces this concept:

"Social determinants of health are the economic and social conditions that shape the health of individuals, communities, and jurisdictions as a whole. Social determinants of health are the primary determinants of whether individuals stay healthy or become ill (a narrow definition of health). Social determinants of health also determine the extent to which a person possesses the physical, social, and personal resources to identify and

achieve personal aspirations, satisfy needs, and cope with the environment (a broader definition of health). Social determinants of health are about the quantity and quality

of a variety of resources that a society makes available to its members." p. 2.

The definitive work on the social determinants is the 2008 report from the World Health Organisation "Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity through Action on the Social Determinants of Health at http://www.who.int/social_determinants/thecommission/finalreport/en/index.html

The definitive Canadian work on the social determinants is the 2009 volume "Social Determinants of Health: Canadian Perspectives" at http://www.cspi.org/books/social_determinants_health

s in Canada since 1900. But by the time vaccines for diseases such as measles, influenza, and polio and treatments for scarlet fever, dramatic declines in mortality had already occurred.

Improvements in behaviour (e.g., reductions in tobacco use, changes in diet, increased exercise, etc.) have also been hypothesized as responsible for improved longevity, but most analysts conclude that improvements in health are due to the improving material conditions of everyday life experienced by Canadians since 1900. These improvements occurred in the areas of early childhood, education, food processing and availability, health and social services, housing, employment security and working conditions and every other social determinant of health.

Instead, evidence indicates that health differences among Canadians result primarily from experiences of qualitatively different living conditions associated with the social determinants of health. As just one example, consider the magnitude of differences in health that are related to the social determinant of health of income. Income is especially important as it serves as a marker of different experiences with many social determinants of health. Income is a determinant of health in itself, but it is also a determinant of the quality of early life, education, employment and working conditions, and food security. Income also is a determinant of the quality of housing, need for a social safety net, the experience of social exclusion, and the experience of unemployment and employment insecurity across the life span

. Also, a key aspect of Aboriginal life and the experience of women in Canada is their greater likelihood of living under conditions of low income.

Income is a prime determinant of Canadians’ premature years of life lost and premature mortality from a range of diseases. Numerous studies indicate that income levels during early childhood, adolescence, and adulthood are all independent predictors of who develops and eventually succumbs to disease.

In Canada almost a quarter of excess premature years of life lost (mortality prior to age 75) can be attributed to income differences among Canadians. These calculations are obtained by using the mortality in the wealthiest quintile of urban neighbourhoods as a baseline and considering all deaths above that level to be “excess” related to income differences. These analyses indicate that 23% of premature years of life lost to Canadians can be accounted for by differences existing between wealthy and other Canadians.

What are the diseases that differentially kill people of varying income levels? Income-related premature years of life lost can be correlated with death certificate cause of death. Among the not-wealthy, mortality by heart disease and stroke are especially related to income differences. Importantly, premature death by injuries, cancers, infectious disease, and diabetes are also all strongly related to not being wealthy in Canada. These rates are especially high among the least well-off Canadians.

In 2002, Statistics Canada

examined the predictors of life expectancy, disability-free life expectancy, and the presence of fair or poor health among residents of 136 regions across Canada. The predictors included socio-demographic factors (proportion of Aboriginal population, proportion of visible minority

population, unemployment rate

, population size, percentage of population aged 65 or over, average income, and average number of years of schooling). Also placed into the analysis were daily smoking rate, obesity rate, infrequent exercise rate, heavy drinking rate, high stress rate, and depression rate.

Consistent with most other research, behavioural risk factors were rather weak predictors of health status as compared to socio-economic and demographic measures of which income is a major component.

For life expectancy, the socio-demographic measures predicted 56% of variation (total variation is 100%) among Canadian communities. Daily smoking rate added only 8% more predictive power, obesity rate only another 1%, and exercise rate nothing at all! For disability-free life expectancy, socio-demographics predicted 32% of variation among communities, and daily smoking rated added only another 6% predictive power, obesity rate another 5%, and exercise rate another 3%. Differences among Canadians communities in numbers of residents reporting poor or fair health were related to socio-demographics (25% predictive power) with smoking rate adding 6%, obesity rate adding 10%, and exercise rate adding 3% predictive power.

Income-related effects are seen therefore in greater incidence and mortality from just about every affliction that Canadians experience. This is especially the case for chronic diseases

. Incidence of, and mortality from, heart disease

and stroke, and adult-onset or type 2 diabetes are especially good examples of the importance of the social determinants of health.

While governments, medical researchers, and public health

workers emphasize the importance of traditional adult risk factors (e.g., cholesterol levels, diet, physical activity, and tobacco and alcohol use), it is well established that these are relatively poor predictors of heart disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes rates among populations. The factors making a difference are living under conditions of material deprivation as children and adults, stress associated with such conditions, and the adoption of health threatening behaviours as means of coping with these difficult circumstances. In fact, difficult living circumstances during childhood are especially good predictors of these diseases.

In addition to predicting adult incidence and death from disease, income differences — and the other social determinants of health related to income — are also related to the health of Canadian children and youth. Canadian children living in low-income

families are more likely to experience greater incidence of a variety of illnesses, hospital stays, accidental injuries, mental health

problems, lower school achievement and early drop-out, family violence and child abuse

, among others. In fact, low-income children show higher incidences of just about any health-, social-, or education-related problem, however defined. These differences in problem incidence occur across the income range but are most concentrated among low-income children.

In one approach the focus is on lifestyle choices. In the other there is a concern with the social determinants of health.

The traditional 10 Tips for Better Health

Ten Tips for Staying Healthy -Gordon, David, 1999

Source: Raphael, D. 2000. The question of evidence in health promotion. Health Promotion International 15: 355-67. Table 3, "The role of ideology in health promotion."

The Social Determinants of Health:

1. Income and Income Distribution

, etc.) common to developing nations. Yet among developed nations such as Canada, less profound but still highly significant differences in health status indicators

such as life expectancy, infant mortality, incidence of disease, and death from injuries exist. An excellent example is comparison of health status differences and the hypothesized social determinants of these health status differences among Canada, the United States, and Sweden.

Scholarship has noted that the USA takes an especially laissez-faire approach to providing various forms of security (employment, food, income, and housing) and health and social services while Sweden’s welfare state

makes extraordinary efforts to provide security and services. The sources of these differences in public policy appear to be in differing commitments to citizen support informed by the political ideologies of governing parties within each nation.

Emerging scholarship is specifically focused on how national approaches to security provision to citizens influence health by shaping the quality of numerous social determinants of health. Nations such as Sweden whose policies reduce unemployment, minimize income and wealth inequality, and address numerous social determinants of health show evidence of improved population health using indicators such as infant mortality and life expectancy. At the other end, nations with minimal commitments to such efforts such as the United States show rather worse indicators of population health.

Finally, poverty is an especially important indicator of how various social determinants of health combine to influence health. Using child – that is family – poverty rates as an important social determinants of both child and eventual health, Canada does not fare well in relation to European nations.

are discussed elsewhere, and groups have formed to lobby regarding these issues.

The cultural/behavioural explanation was that individuals' behavioural choices (e.g., tobacco and alcohol use, diet, physical activity, etc.) were responsible for their developing and dying from a variety of diseases. Both the Black and Health divide reports however, showed that behavioural choices are heavily structured by one’s material conditions of life. And—consistent with mounting evidence—these behavioural risk factors account for a relatively small proportion of variation in the incidence and death from various diseases. The materialist/structuralist explanation emphasizes the material conditions under which people live their lives. These conditions include availability of resources to access the amenities of life, working conditions, and quality of available food and housing among others.

The author of the Health Divide concluded: The weight of evidence continues to point to explanations which suggest that socio-economic circumstances play the major part in subsequent health differences. Despite this conclusion and increasing evidence in favour of this view, much of the Canadian public discourse on health and disease

remains focused on “life-style” approaches to disease prevention.

These materialist/structuralist conceptualizations have been refined such that analysis is now focused upon three frameworks by which social determinants of health come to influence health. These frameworks are: (a) materialist; (b) neo-materialist; and (c) psychosocial comparison. The materialist explanation is about how living conditions – and the social determinants of health that constitute these living conditions—shape health. The neo-materialist explanation extends the materialist analysis by asking how these living conditions come about. The psychosocial comparison explanation considers whether people compare themselves to others and how these comparisons affect health and wellbeing.

In this argument individuals experience varying degrees of positive and negative exposures over their lives that accumulate to produce adult health outcomes. Overall wealth of nations

is a strong indicator of population health. But within nations, socio-economic position is a powerful predictor of health as it is an indicator of material advantage or disadvantage over the lifespan. Material conditions of life determine health by influencing the quality of individual development, family life and interaction, and community environments. Material conditions of life lead to differing likelihood of physical (infections, malnutrition, chronic disease, and injuries), developmental (delayed or impaired cognitive, personality, and social development), educational (learning disabilities, poor learning, early school leaving), and social (socialization, preparation for work, and family life) problems.

Material conditions of life also lead to differences in psychosocial stress The fight-or-flight reaction—chronically elicited in response to threats such as income, housing, and food insecurity, among others—weakens the immune system, leads to increased insulin resistance, greater incidence of lipid and clotting disorders, and other biomedical insults that are precursors to adult disease.

Adoption of health-threatening behaviours is a response to material

deprivation and stress. Environments determine whether individuals take up tobacco, use alcohol, experience poor diets, and have low levels of physical activity. Tobacco and excessive alcohol use, and carbohydrate-dense diets are also means of coping with difficult circumstances. Materialist arguments help us understand the sources of health inequalities among individuals and nations and the role played by the social determinants of health.

In the USA, states and cities with more unequal distributions of income have more low-income people and greater income gaps between rich and poor. They invest less in public infrastructure such as education, health and social services, health insurance

, supports for the unemployed and those with disabilities, and spend less on education and libraries. All of these issues contribute to the quality of the social determinants of health to which people are exposed. Such unequal jurisdictions have much poorer health profiles than more equalitarian places.

Canada has a smaller proportion of lower-income people, a smaller gap between rich and poor, and spends relatively more on public infrastructure than the U.S. Not surprisingly, Canadians enjoy better health than Americans which is measured by infant mortality rates, life expectancy, and death rates

from childhood injuries. Neither nation does as well as Sweden where distribution of resources is much more equalitarian, low-income rates are very low, and health indicators are among the best in the world.

The neo-materialist view therefore, directs attention to both the effects of living conditions – the social determinants of health—on individuals' health and the societal factors that determine the quality of the distribution of these social determinants of health. How a society decides to distribute resources among citizens is especially important.

At the individual level, the perception and experience of one’s status in unequal societies lead to stress and poor health. Comparing their status, possessions, and other life circumstances to those better-off than themselves, individuals experience feelings of shame, worthlessness, and envy that have psychobiological effects upon health. These processes involve direct disease-producing effects upon neuro-endocrine, autonomic and metabolic, and immune systems. These comparisons can also lead to attempts to alleviate such feelings by overspending, taking on additional employment that threaten health, and adopting health-threatening coping behaviours such as overeating and using alcohol and tobacco.

At the communal level, widening and strengthening of hierarchy weakens social cohesion

, a determinant of health. Individuals become more distrusting and suspicious of others with direct stress-related effects on the body. Such attitudes can also weaken support for communal structures such as public education, health, and social programs. An exaggerated desire for tax reductions on the part of the public can weaken public infrastructure.

This approach directs attention to the psychosocial effects of public policies that weaken the social determinants of health. But these effects may be secondary to how societies distribute material resources and provide security to its citizens – processes described in the materialist and neo-materialist approaches. Material aspects may be paramount and the stresses associated with deprivation simply add to the toll on individuals’ bodies.

“The prevailing aetiological model for adult disease which emphasizes adult risk factors, particularly aspects of adult life style, has been challenged in recent years by research that has shown that poor growth and development and adverse early environmental conditions are associated with an increased risk of adult chronic disease" Kuh, D., & Ben-Shilmo, Y. (Eds.). (1997). A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press,p.3.

More specifically, it is apparent that the economic and social conditions—the social determinants of health—under which individuals live their lives have a cumulative effect upon the probability of developing any number of diseases. This has been repeatedly demonstrated in longitudinal studies—the U.S. National Longitudinal Survey, the West of Scotland Collaborative Study, Norwegian and Finnish linked data—which follow individuals across their lives. This has been most clearly demonstrated in the case of heart disease and stroke. And most recently, studies into the childhood and adulthood antecedents of adult-onset diabetes show how adverse economic and social conditions across the life span predispose individuals to this disorder.

A recent volume brings together some of the important work concerning the importance of a life-course perspective for understanding the importance of social determinants. Adopting a life-course perspective directs attention to how social determinants of health operate at every level of development—early childhood, childhood, adolescence, and adulthood—to both immediately influence health as well as provide the basis for health or illness during later stages of the life course.

Hertzman outlines three health effect

s that have relevance for a life-course perspective. Latent effects are biological or developmental early life experiences that influence health later in life. Low birth weight

, for instance, is a reliable predictor of incidence of cardiovascular disease and adult-onset diabetes in later life. Experience of nutritional deprivation during childhood has lasting health effects.

Pathway effects are experiences that set individuals onto trajectories that influence health, well-being, and competence over the life course. As one example, children who enter school with delayed vocabulary are set upon a path that leads to lower educational expectations, poor employment prospects, and greater likelihood of illness and disease across the lifespan. Deprivation associated with poor-quality neighbourhoods, schools, and housing sets children off on paths that are not conducive to health and well-being.

Cumulative effects are the accumulation of advantage or disadvantage over time that manifests itself in poor health. These involve the combination of latent and pathways effects. Adopting a life-course perspective directs attention to how social determinants of health operate at every level of development—early childhood, childhood, adolescence, and adulthood—to both immediately influence health and provide the basis for health or illness later in life.

Social determinants of health do not exist in a vacuum. Their quality and availability to the population are usually a result of public policy decisions made by governing authorities. As one example, consider the social determinant of health of early life. Early life is shaped by availability of sufficient material resources that assure adequate educational opportunities, food and housing among others. Much of this has to do with the employment security and the quality of working conditions and wages. The availability of quality, regulated childcare is an especially important policy option in support of early life. These are not issues that usually come under individual control. A policy-oriented approach places such findings within a broader policy context.

Yet it is not uncommon to see governmental and other authorities individualize these issues. Governments may choose to understand early life as being primarily about parental behaviours towards their children. They then focus upon promoting better parenting, assist in having parents read to their children, or urge schools to foster exercise among children rather than raising the amount of financial or housing resources available to families. Indeed, for every social determinant of health, an individualized manifestation of each is available. There is little evidence to suggest the efficacy of such approaches in improving the health status of those most vulnerable to illness in the absence of efforts to modify their adverse living conditions.

Two literatures inform this analysis. The first concerns the three forms of the modern welfare state. Esping-Andersen identifies three distinct clusters of welfare regimes among wealthy developed nations: Social Democratic

(e.g., Sweden, Norway, Denmark, and Finland), Liberal (USA, UK, Canada, Ireland), and Conservative (France, Germany, Netherlands, and Belgium, among others). There is high government intervention and strong welfare systems in the social democratic countries and rather less in the liberal. Conservative nations fall midway between these others in service provision and citizen supports.

Social democratic nations have very well developed welfare states that provide a wide range of universal and generous benefits. They expend more of national wealth to supports and services. They are proactive in developing labour, family-friendly, and gender equity supporting policies. Liberal nations spend rather less on supports and services. They offer modest universal transfers and modest social-insurance plans. Benefits are provided primarily through means-tested assistance whereby these benefits are only provided to the least well-off.

Navarro and colleagues provide empirical support for the hypotheses that the social determinants of health are less unequal and health status outcomes are of higher quality in the social democratic rather than the liberal nations. Some of these indicators are spending on supports and services, equalization

of incomes, and wealth and availability of services in support of families and individuals. Health indicators include life expectancy and infant mortality.

Could this general approach to welfare provision shape Canadian receptivity to the concepts developed in this volume? And if so, what can be done to improve receptivity to and implementation of these concepts? The final chapter of this volume revisits these issues.

A particularly important issue that is emerging is whether any particular analysis of social determinants of health is de-politicized or not. A de-politicized approach is one that fails to take account of the fact that the quality of the social determinants of health to which citizens in a jurisdiction are exposed to is shaped by public policy created by governments. And governments of course are controlled by political parties who come to power with a set of ideological beliefs concerning the nature of society and the role of governments.

Such analyses that recognize the role played by politics outline the particular importance of having social democratic political parties in power. Nations that have had longer periods of social democratic influence such as Norway, Finland, Sweden, and Denmark have government policymaking that is remarkably consistent with social determinants of health concepts. Nations such as the USA and Canada,dominated by liberal and neo-liberal governing parties, much less so.

A wealth of evidence from Canada and other countries supports the notion that the socioeconomic circumstances of individuals and groups are equally or more important to health status than medical care and personal health behaviours, such as smoking and eating patterns.

A wealth of evidence from Canada and other countries supports the notion that the socioeconomic circumstances of individuals and groups are equally or more important to health status than medical care and personal health behaviours, such as smoking and eating patterns.

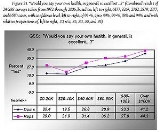

An example of SDOH, applicable to the United States, is shown in the graph. It shows self-reported health as it relates to income level and political party identification (Democrat vs. Republican).

The weight of the evidence suggests that the SDOH have a direct impact on the health of individuals and populations, are the best predictors of individual and population health, structure lifestyle choices, and interact with each other to produce health (Raphael, 2003). In terms of the health of populations, it is well known that disparities-the size of the gap or inequality in social and economic status between groups within a given population-greatly affect the health status of the whole. The larger the gap, the lower the health status of the overall population.

Health

Health is the level of functional or metabolic efficiency of a living being. In humans, it is the general condition of a person's mind, body and spirit, usually meaning to be free from illness, injury or pain...

. They are "societal risk conditions", rather than individual risk factor

Risk factor

In epidemiology, a risk factor is a variable associated with an increased risk of disease or infection. Sometimes, determinant is also used, being a variable associated with either increased or decreased risk.-Correlation vs causation:...

s that either increase or decrease the risk for a disease

Disease

A disease is an abnormal condition affecting the body of an organism. It is often construed to be a medical condition associated with specific symptoms and signs. It may be caused by external factors, such as infectious disease, or it may be caused by internal dysfunctions, such as autoimmune...

, for example for cardiovascular disease

Cardiovascular disease

Heart disease or cardiovascular disease are the class of diseases that involve the heart or blood vessels . While the term technically refers to any disease that affects the cardiovascular system , it is usually used to refer to those related to atherosclerosis...

and type II diabetes.

A succinct statement of what they are and why they are important can be found at http://thecanadianfacts.org

As stated in Social Determinants of Health: The Solid Facts (WHO, 2003):

"Health policy was once thought to be about little more than the provision and funding of medical care: the social determinants of health were discussed only among academics. This is now changing. While medical care can prolong survival and improve prognosis after some serious diseases, more important for the health of the population as a whole are the social and economic conditions that make people ill and in need of medical care in the first place. Nevertheless, universal access to medical care is clearly one of the social determinants of health."

Raphael (2008) reinforces this concept:

"Social determinants of health are the economic and social conditions that shape the health of individuals, communities, and jurisdictions as a whole. Social determinants of health are the primary determinants of whether individuals stay healthy or become ill (a narrow definition of health). Social determinants of health also determine the extent to which a person possesses the physical, social, and personal resources to identify and

achieve personal aspirations, satisfy needs, and cope with the environment (a broader definition of health). Social determinants of health are about the quantity and quality

of a variety of resources that a society makes available to its members." p. 2.

The definitive work on the social determinants is the 2008 report from the World Health Organisation "Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity through Action on the Social Determinants of Health at http://www.who.int/social_determinants/thecommission/finalreport/en/index.html

The definitive Canadian work on the social determinants is the 2009 volume "Social Determinants of Health: Canadian Perspectives" at http://www.cspi.org/books/social_determinants_health

Improving Health Status

Profound improvements in health status have occurred in industrialized nations such as Canada since 1900. It has been hypothesized that access to improved medical care is responsible for these differences, but best estimates are that only 10–15 percent of increased longevity since 1900 in wealthy industrialized nations is due to improved health care. As one illustration, the advent of vaccines and medical treatments are usually held responsible for the profound declines in mortality from infectious diseaseInfectious disease

Infectious diseases, also known as communicable diseases, contagious diseases or transmissible diseases comprise clinically evident illness resulting from the infection, presence and growth of pathogenic biological agents in an individual host organism...

s in Canada since 1900. But by the time vaccines for diseases such as measles, influenza, and polio and treatments for scarlet fever, dramatic declines in mortality had already occurred.

Improvements in behaviour (e.g., reductions in tobacco use, changes in diet, increased exercise, etc.) have also been hypothesized as responsible for improved longevity, but most analysts conclude that improvements in health are due to the improving material conditions of everyday life experienced by Canadians since 1900. These improvements occurred in the areas of early childhood, education, food processing and availability, health and social services, housing, employment security and working conditions and every other social determinant of health.

Inequalities among Canadians

Despite dramatic improvements in health in general, significant inequalities in health among Canadians persist. Access to essential medical procedures is guaranteed by Medicare in Canada. Nevertheless, access to care issues are common and this is particularly the case in regards to required prescription medicines where income is a strong determinant of such access. It is believed however that health care issues account for a relatively small proportion of health status differences that exist among Canadians. As for differences in health behaviours (e.g., tobacco and alcohol use, diet, and physical activity, etc.), studies from as early as the mid 1970s—reinforced by many more studies since then—find their impact upon health to be less important than social determinants of health such as income and other social determinants of health.Instead, evidence indicates that health differences among Canadians result primarily from experiences of qualitatively different living conditions associated with the social determinants of health. As just one example, consider the magnitude of differences in health that are related to the social determinant of health of income. Income is especially important as it serves as a marker of different experiences with many social determinants of health. Income is a determinant of health in itself, but it is also a determinant of the quality of early life, education, employment and working conditions, and food security. Income also is a determinant of the quality of housing, need for a social safety net, the experience of social exclusion, and the experience of unemployment and employment insecurity across the life span

Life expectancy

Life expectancy is the expected number of years of life remaining at a given age. It is denoted by ex, which means the average number of subsequent years of life for someone now aged x, according to a particular mortality experience...

. Also, a key aspect of Aboriginal life and the experience of women in Canada is their greater likelihood of living under conditions of low income.

Income is a prime determinant of Canadians’ premature years of life lost and premature mortality from a range of diseases. Numerous studies indicate that income levels during early childhood, adolescence, and adulthood are all independent predictors of who develops and eventually succumbs to disease.

In Canada almost a quarter of excess premature years of life lost (mortality prior to age 75) can be attributed to income differences among Canadians. These calculations are obtained by using the mortality in the wealthiest quintile of urban neighbourhoods as a baseline and considering all deaths above that level to be “excess” related to income differences. These analyses indicate that 23% of premature years of life lost to Canadians can be accounted for by differences existing between wealthy and other Canadians.

What are the diseases that differentially kill people of varying income levels? Income-related premature years of life lost can be correlated with death certificate cause of death. Among the not-wealthy, mortality by heart disease and stroke are especially related to income differences. Importantly, premature death by injuries, cancers, infectious disease, and diabetes are also all strongly related to not being wealthy in Canada. These rates are especially high among the least well-off Canadians.

In 2002, Statistics Canada

Statistics Canada

Statistics Canada is the Canadian federal government agency commissioned with producing statistics to help better understand Canada, its population, resources, economy, society, and culture. Its headquarters is in Ottawa....

examined the predictors of life expectancy, disability-free life expectancy, and the presence of fair or poor health among residents of 136 regions across Canada. The predictors included socio-demographic factors (proportion of Aboriginal population, proportion of visible minority

Visible minority

A visible minority is a person who is visibly not one of the majority race in a given population.The term is used as a demographic category by Statistics Canada in connection with that country's Employment Equity policies. The qualifier "visible" is important in the Canadian context where...

population, unemployment rate

Unemployment

Unemployment , as defined by the International Labour Organization, occurs when people are without jobs and they have actively sought work within the past four weeks...

, population size, percentage of population aged 65 or over, average income, and average number of years of schooling). Also placed into the analysis were daily smoking rate, obesity rate, infrequent exercise rate, heavy drinking rate, high stress rate, and depression rate.

Consistent with most other research, behavioural risk factors were rather weak predictors of health status as compared to socio-economic and demographic measures of which income is a major component.

For life expectancy, the socio-demographic measures predicted 56% of variation (total variation is 100%) among Canadian communities. Daily smoking rate added only 8% more predictive power, obesity rate only another 1%, and exercise rate nothing at all! For disability-free life expectancy, socio-demographics predicted 32% of variation among communities, and daily smoking rated added only another 6% predictive power, obesity rate another 5%, and exercise rate another 3%. Differences among Canadians communities in numbers of residents reporting poor or fair health were related to socio-demographics (25% predictive power) with smoking rate adding 6%, obesity rate adding 10%, and exercise rate adding 3% predictive power.

Income-related effects are seen therefore in greater incidence and mortality from just about every affliction that Canadians experience. This is especially the case for chronic diseases

Chronic (medicine)

A chronic disease is a disease or other human health condition that is persistent or long-lasting in nature. The term chronic is usually applied when the course of the disease lasts for more than three months. Common chronic diseases include asthma, cancer, diabetes and HIV/AIDS.In medicine, the...

. Incidence of, and mortality from, heart disease

Heart disease

Heart disease, cardiac disease or cardiopathy is an umbrella term for a variety of diseases affecting the heart. , it is the leading cause of death in the United States, England, Canada and Wales, accounting for 25.4% of the total deaths in the United States.-Types:-Coronary heart disease:Coronary...

and stroke, and adult-onset or type 2 diabetes are especially good examples of the importance of the social determinants of health.

While governments, medical researchers, and public health

Public health

Public health is "the science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life and promoting health through the organized efforts and informed choices of society, organizations, public and private, communities and individuals" . It is concerned with threats to health based on population health...

workers emphasize the importance of traditional adult risk factors (e.g., cholesterol levels, diet, physical activity, and tobacco and alcohol use), it is well established that these are relatively poor predictors of heart disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes rates among populations. The factors making a difference are living under conditions of material deprivation as children and adults, stress associated with such conditions, and the adoption of health threatening behaviours as means of coping with these difficult circumstances. In fact, difficult living circumstances during childhood are especially good predictors of these diseases.

In addition to predicting adult incidence and death from disease, income differences — and the other social determinants of health related to income — are also related to the health of Canadian children and youth. Canadian children living in low-income

Poverty

Poverty is the lack of a certain amount of material possessions or money. Absolute poverty or destitution is inability to afford basic human needs, which commonly includes clean and fresh water, nutrition, health care, education, clothing and shelter. About 1.7 billion people are estimated to live...

families are more likely to experience greater incidence of a variety of illnesses, hospital stays, accidental injuries, mental health

Mental health

Mental health describes either a level of cognitive or emotional well-being or an absence of a mental disorder. From perspectives of the discipline of positive psychology or holism mental health may include an individual's ability to enjoy life and procure a balance between life activities and...

problems, lower school achievement and early drop-out, family violence and child abuse

Child abuse

Child abuse is the physical, sexual, emotional mistreatment, or neglect of a child. In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Department of Children And Families define child maltreatment as any act or series of acts of commission or omission by a parent or...

, among others. In fact, low-income children show higher incidences of just about any health-, social-, or education-related problem, however defined. These differences in problem incidence occur across the income range but are most concentrated among low-income children.

In one approach the focus is on lifestyle choices. In the other there is a concern with the social determinants of health.

The traditional 10 Tips for Better Health

- 1. Don't smoke. If you can, stop. If you can't, cut down.

- 2. Follow a balanced diet with plenty of fruit and vegetables.

- 3. Keep physically active.

- 4. Manage stress by, for example, talking things through and making time to relax.

- 5. If you drink alcohol, do so in moderation.

- 6. Cover up in the sun, and protect children from sunburn.

- 7. Practice safer sexSafe sexSafe sex is sexual activity engaged in by people who have taken precautions to protect themselves against sexually transmitted diseases such as AIDS. It is also referred to as safer sex or protected sex, while unsafe or unprotected sex is sexual activity engaged in without precautions...

. - 8. Take up cancer-screening opportunities.

- 9. Be safe on the roads: follow the Highway Code.

- 10. Learn the First Aid ABCs: airways, breathing, circulation.

Ten Tips for Staying Healthy -Gordon, David, 1999

- 1. Don’t be poor. If you can, stop. If you can’t, try not to be poor for long.

- 2. Don’t have poor parents.

- 3. Own a car.

- 4. Don’t work in a stressful, low paid manual job.

- 5. Don’t live in damp, low quality housing.

- 6. Be able to afford to go on a foreign holiday and sunbathe.

- 7. Practice not losing your job and don’t become unemployed.

- 8. Take up all benefits you are entitled to, if you are unemployed, retired or sick or disabled.

- 9. Don’t live next to a busy major road or near a polluting factory.

- 10. Learn how to fill in the complex housing benefit/ asylum application forms before you become homeless and destitute.

Source: Raphael, D. 2000. The question of evidence in health promotion. Health Promotion International 15: 355-67. Table 3, "The role of ideology in health promotion."

The Social Determinants of Health:

1. Income and Income Distribution

2. Education

3. Unemployment and Job Security

4. Employment and Working Conditions

5. Early Childhood Development

6. Food Insecurity

7. Housing

8. Social Exclusion

9. Social Safety Network

10. Health Services

11. Aboriginal Status

12. Gender

13. Race

14. Disability

Source: http://www.thecanadianfacts.org/

Between developed countries

Profound differences in overall health status exist between developed and developing nations. Much of this has to do with the lack of the basic necessities of life (food, water, sanitation, primary health carePrimary health care

Primary health care, often abbreviated as “PHC”, has been defined as "essential health care based on practical, scientifically sound and socially acceptable methods and technology made universally accessible to individuals and families in the community through their full participation and at a cost...

, etc.) common to developing nations. Yet among developed nations such as Canada, less profound but still highly significant differences in health status indicators

ICU scoring systems

-Adult scoring systems:* APACHE II was designed to provide a morbidity score for a patient. It is useful to decide what kind of treatment or medicine is given...

such as life expectancy, infant mortality, incidence of disease, and death from injuries exist. An excellent example is comparison of health status differences and the hypothesized social determinants of these health status differences among Canada, the United States, and Sweden.

Scholarship has noted that the USA takes an especially laissez-faire approach to providing various forms of security (employment, food, income, and housing) and health and social services while Sweden’s welfare state

Welfare state

A welfare state is a "concept of government in which the state plays a key role in the protection and promotion of the economic and social well-being of its citizens. It is based on the principles of equality of opportunity, equitable distribution of wealth, and public responsibility for those...

makes extraordinary efforts to provide security and services. The sources of these differences in public policy appear to be in differing commitments to citizen support informed by the political ideologies of governing parties within each nation.

Emerging scholarship is specifically focused on how national approaches to security provision to citizens influence health by shaping the quality of numerous social determinants of health. Nations such as Sweden whose policies reduce unemployment, minimize income and wealth inequality, and address numerous social determinants of health show evidence of improved population health using indicators such as infant mortality and life expectancy. At the other end, nations with minimal commitments to such efforts such as the United States show rather worse indicators of population health.

Finally, poverty is an especially important indicator of how various social determinants of health combine to influence health. Using child – that is family – poverty rates as an important social determinants of both child and eventual health, Canada does not fare well in relation to European nations.

Between developing and developed countries

People in rich countries live dramatically longer, healthier lives than people in poorer countries. It can be argued that it is the huge wealth inequalities between rich and poor countries that is acting as a fundamental driver of poor global health. The causes of wealth inequalitiesInternational inequality

International inequality is inequality between countries . Economic differences between rich and poor countries are considerable...

are discussed elsewhere, and groups have formed to lobby regarding these issues.

Cultural and Structuralist Approaches

To secure attention to the social determinants of health and build support for their strengthening, it is important to understand how social determinants of health come to influence health and cause disease. The very influential UK Black and The Health Divide reports considered two primary mechanisms for understanding this process: cultural/ behavioural and materialist/structuralist.The cultural/behavioural explanation was that individuals' behavioural choices (e.g., tobacco and alcohol use, diet, physical activity, etc.) were responsible for their developing and dying from a variety of diseases. Both the Black and Health divide reports however, showed that behavioural choices are heavily structured by one’s material conditions of life. And—consistent with mounting evidence—these behavioural risk factors account for a relatively small proportion of variation in the incidence and death from various diseases. The materialist/structuralist explanation emphasizes the material conditions under which people live their lives. These conditions include availability of resources to access the amenities of life, working conditions, and quality of available food and housing among others.

The author of the Health Divide concluded: The weight of evidence continues to point to explanations which suggest that socio-economic circumstances play the major part in subsequent health differences. Despite this conclusion and increasing evidence in favour of this view, much of the Canadian public discourse on health and disease

Disease

A disease is an abnormal condition affecting the body of an organism. It is often construed to be a medical condition associated with specific symptoms and signs. It may be caused by external factors, such as infectious disease, or it may be caused by internal dysfunctions, such as autoimmune...

remains focused on “life-style” approaches to disease prevention.

These materialist/structuralist conceptualizations have been refined such that analysis is now focused upon three frameworks by which social determinants of health come to influence health. These frameworks are: (a) materialist; (b) neo-materialist; and (c) psychosocial comparison. The materialist explanation is about how living conditions – and the social determinants of health that constitute these living conditions—shape health. The neo-materialist explanation extends the materialist analysis by asking how these living conditions come about. The psychosocial comparison explanation considers whether people compare themselves to others and how these comparisons affect health and wellbeing.

In this argument individuals experience varying degrees of positive and negative exposures over their lives that accumulate to produce adult health outcomes. Overall wealth of nations

The Wealth of Nations

An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, generally referred to by its shortened title The Wealth of Nations, is the magnum opus of the Scottish economist and moral philosopher Adam Smith...

is a strong indicator of population health. But within nations, socio-economic position is a powerful predictor of health as it is an indicator of material advantage or disadvantage over the lifespan. Material conditions of life determine health by influencing the quality of individual development, family life and interaction, and community environments. Material conditions of life lead to differing likelihood of physical (infections, malnutrition, chronic disease, and injuries), developmental (delayed or impaired cognitive, personality, and social development), educational (learning disabilities, poor learning, early school leaving), and social (socialization, preparation for work, and family life) problems.

Material conditions of life also lead to differences in psychosocial stress The fight-or-flight reaction—chronically elicited in response to threats such as income, housing, and food insecurity, among others—weakens the immune system, leads to increased insulin resistance, greater incidence of lipid and clotting disorders, and other biomedical insults that are precursors to adult disease.

Adoption of health-threatening behaviours is a response to material

Techno-organic material

In fiction, techno-organic material is a material with properties and abilities of both organic and technological material.-Use in Fiction:...

deprivation and stress. Environments determine whether individuals take up tobacco, use alcohol, experience poor diets, and have low levels of physical activity. Tobacco and excessive alcohol use, and carbohydrate-dense diets are also means of coping with difficult circumstances. Materialist arguments help us understand the sources of health inequalities among individuals and nations and the role played by the social determinants of health.

Neo-materialist approach

Exposures to the material conditions of life are important for health, but why are these material conditions so unequally distributed among the Canadian population but less so elsewhere?. The neo-materialist approach is concerned with how nations, regions, and cities differ on how economic and other resources are distributed among the population. Some jurisdictions have more equalitarian distribution of resources such that there are fewer poor people and the gaps that exist among the population in their exposures to the social determinants of health is narrower than places where there are more poor people and the gaps among the population are greater.In the USA, states and cities with more unequal distributions of income have more low-income people and greater income gaps between rich and poor. They invest less in public infrastructure such as education, health and social services, health insurance

Health insurance

Health insurance is insurance against the risk of incurring medical expenses among individuals. By estimating the overall risk of health care expenses among a targeted group, an insurer can develop a routine finance structure, such as a monthly premium or payroll tax, to ensure that money is...

, supports for the unemployed and those with disabilities, and spend less on education and libraries. All of these issues contribute to the quality of the social determinants of health to which people are exposed. Such unequal jurisdictions have much poorer health profiles than more equalitarian places.

Canada has a smaller proportion of lower-income people, a smaller gap between rich and poor, and spends relatively more on public infrastructure than the U.S. Not surprisingly, Canadians enjoy better health than Americans which is measured by infant mortality rates, life expectancy, and death rates

Mortality rate

Mortality rate is a measure of the number of deaths in a population, scaled to the size of that population, per unit time...

from childhood injuries. Neither nation does as well as Sweden where distribution of resources is much more equalitarian, low-income rates are very low, and health indicators are among the best in the world.

The neo-materialist view therefore, directs attention to both the effects of living conditions – the social determinants of health—on individuals' health and the societal factors that determine the quality of the distribution of these social determinants of health. How a society decides to distribute resources among citizens is especially important.

Social comparison approach

The argument here is that the social determinants of health play their role through citizens’ interpretations of their standings in the social hierarchy. There are two mechanisms by which this occurs.At the individual level, the perception and experience of one’s status in unequal societies lead to stress and poor health. Comparing their status, possessions, and other life circumstances to those better-off than themselves, individuals experience feelings of shame, worthlessness, and envy that have psychobiological effects upon health. These processes involve direct disease-producing effects upon neuro-endocrine, autonomic and metabolic, and immune systems. These comparisons can also lead to attempts to alleviate such feelings by overspending, taking on additional employment that threaten health, and adopting health-threatening coping behaviours such as overeating and using alcohol and tobacco.

At the communal level, widening and strengthening of hierarchy weakens social cohesion

Social cohesion

Social cohesion is a term used in social policy, sociology and political science to describe the bonds or "glue" that bring people together in society, particularly in the context of cultural diversity. Social cohesion is a multi-faceted notion covering many different kinds of social phenomena...

, a determinant of health. Individuals become more distrusting and suspicious of others with direct stress-related effects on the body. Such attitudes can also weaken support for communal structures such as public education, health, and social programs. An exaggerated desire for tax reductions on the part of the public can weaken public infrastructure.

This approach directs attention to the psychosocial effects of public policies that weaken the social determinants of health. But these effects may be secondary to how societies distribute material resources and provide security to its citizens – processes described in the materialist and neo-materialist approaches. Material aspects may be paramount and the stresses associated with deprivation simply add to the toll on individuals’ bodies.

Life-course perspective

Traditional approaches to health and disease prevention have a distinctly non-historical here-and-now emphasis. Usually adults, and increasingly adolescents and youth are urged to adopt “healthy lifestyles” as a means of preventing the development of chronic diseases such as heart disease and diabetes, among others. In contrast to these approaches, life-course approaches emphasize the accumulated effects of experience across the life span in understanding the maintenance of health and the onset of disease. It has been argued:“The prevailing aetiological model for adult disease which emphasizes adult risk factors, particularly aspects of adult life style, has been challenged in recent years by research that has shown that poor growth and development and adverse early environmental conditions are associated with an increased risk of adult chronic disease" Kuh, D., & Ben-Shilmo, Y. (Eds.). (1997). A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press,p.3.

More specifically, it is apparent that the economic and social conditions—the social determinants of health—under which individuals live their lives have a cumulative effect upon the probability of developing any number of diseases. This has been repeatedly demonstrated in longitudinal studies—the U.S. National Longitudinal Survey, the West of Scotland Collaborative Study, Norwegian and Finnish linked data—which follow individuals across their lives. This has been most clearly demonstrated in the case of heart disease and stroke. And most recently, studies into the childhood and adulthood antecedents of adult-onset diabetes show how adverse economic and social conditions across the life span predispose individuals to this disorder.

A recent volume brings together some of the important work concerning the importance of a life-course perspective for understanding the importance of social determinants. Adopting a life-course perspective directs attention to how social determinants of health operate at every level of development—early childhood, childhood, adolescence, and adulthood—to both immediately influence health as well as provide the basis for health or illness during later stages of the life course.

Hertzman outlines three health effect

Health effect

Health effects are changes in health resulting from exposure to a source. Health effects are an important consideration in many areas, such as hygiene, pollution studies, workplace safety, nutrition and health sciences in general...

s that have relevance for a life-course perspective. Latent effects are biological or developmental early life experiences that influence health later in life. Low birth weight

Birth weight

Birth weight is the body weight of a baby at its birth.There have been numerous studies that have attempted, with varying degrees of success, to show links between birth weight and later-life conditions, including diabetes, obesity, tobacco smoking and intelligence.-Determinants:There are...

, for instance, is a reliable predictor of incidence of cardiovascular disease and adult-onset diabetes in later life. Experience of nutritional deprivation during childhood has lasting health effects.

Pathway effects are experiences that set individuals onto trajectories that influence health, well-being, and competence over the life course. As one example, children who enter school with delayed vocabulary are set upon a path that leads to lower educational expectations, poor employment prospects, and greater likelihood of illness and disease across the lifespan. Deprivation associated with poor-quality neighbourhoods, schools, and housing sets children off on paths that are not conducive to health and well-being.

Cumulative effects are the accumulation of advantage or disadvantage over time that manifests itself in poor health. These involve the combination of latent and pathways effects. Adopting a life-course perspective directs attention to how social determinants of health operate at every level of development—early childhood, childhood, adolescence, and adulthood—to both immediately influence health and provide the basis for health or illness later in life.

Public policy

Much social determinants of health research simply focuses on determining the relationship between a social determinant of health and health status. So a researcher may document that lower income is associated with adverse health outcomes among parents and their children. Or a researcher may demonstrate that food insecurity is related to poor health status among parents and children as is living in crowded housing, and so on. This is what is termed a depoliticized approach in that it says little about how these poor-quality social determinants of health come about.Social determinants of health do not exist in a vacuum. Their quality and availability to the population are usually a result of public policy decisions made by governing authorities. As one example, consider the social determinant of health of early life. Early life is shaped by availability of sufficient material resources that assure adequate educational opportunities, food and housing among others. Much of this has to do with the employment security and the quality of working conditions and wages. The availability of quality, regulated childcare is an especially important policy option in support of early life. These are not issues that usually come under individual control. A policy-oriented approach places such findings within a broader policy context.

Yet it is not uncommon to see governmental and other authorities individualize these issues. Governments may choose to understand early life as being primarily about parental behaviours towards their children. They then focus upon promoting better parenting, assist in having parents read to their children, or urge schools to foster exercise among children rather than raising the amount of financial or housing resources available to families. Indeed, for every social determinant of health, an individualized manifestation of each is available. There is little evidence to suggest the efficacy of such approaches in improving the health status of those most vulnerable to illness in the absence of efforts to modify their adverse living conditions.

Politics and political ideology

One way to think about this is to consider the idea of the welfare state and the political ideologies that shape its form in Canada and elsewhere. The concept of the welfare state is about the extent to which governments – or the state – use their power to provide citizens with the means to live secure and satisfying lives. Every developed nation has some form of the welfare state.Two literatures inform this analysis. The first concerns the three forms of the modern welfare state. Esping-Andersen identifies three distinct clusters of welfare regimes among wealthy developed nations: Social Democratic

Social democracy

Social democracy is a political ideology of the center-left on the political spectrum. Social democracy is officially a form of evolutionary reformist socialism. It supports class collaboration as the course to achieve socialism...

(e.g., Sweden, Norway, Denmark, and Finland), Liberal (USA, UK, Canada, Ireland), and Conservative (France, Germany, Netherlands, and Belgium, among others). There is high government intervention and strong welfare systems in the social democratic countries and rather less in the liberal. Conservative nations fall midway between these others in service provision and citizen supports.

Social democratic nations have very well developed welfare states that provide a wide range of universal and generous benefits. They expend more of national wealth to supports and services. They are proactive in developing labour, family-friendly, and gender equity supporting policies. Liberal nations spend rather less on supports and services. They offer modest universal transfers and modest social-insurance plans. Benefits are provided primarily through means-tested assistance whereby these benefits are only provided to the least well-off.

Navarro and colleagues provide empirical support for the hypotheses that the social determinants of health are less unequal and health status outcomes are of higher quality in the social democratic rather than the liberal nations. Some of these indicators are spending on supports and services, equalization

Division of property

Division of property, also known as equitable distribution, is a judicial division of property rights and obligations between spouses during divorce...

of incomes, and wealth and availability of services in support of families and individuals. Health indicators include life expectancy and infant mortality.

Could this general approach to welfare provision shape Canadian receptivity to the concepts developed in this volume? And if so, what can be done to improve receptivity to and implementation of these concepts? The final chapter of this volume revisits these issues.

A particularly important issue that is emerging is whether any particular analysis of social determinants of health is de-politicized or not. A de-politicized approach is one that fails to take account of the fact that the quality of the social determinants of health to which citizens in a jurisdiction are exposed to is shaped by public policy created by governments. And governments of course are controlled by political parties who come to power with a set of ideological beliefs concerning the nature of society and the role of governments.

Such analyses that recognize the role played by politics outline the particular importance of having social democratic political parties in power. Nations that have had longer periods of social democratic influence such as Norway, Finland, Sweden, and Denmark have government policymaking that is remarkably consistent with social determinants of health concepts. Nations such as the USA and Canada,dominated by liberal and neo-liberal governing parties, much less so.

An example of SDOH, applicable to the United States, is shown in the graph. It shows self-reported health as it relates to income level and political party identification (Democrat vs. Republican).

The weight of the evidence suggests that the SDOH have a direct impact on the health of individuals and populations, are the best predictors of individual and population health, structure lifestyle choices, and interact with each other to produce health (Raphael, 2003). In terms of the health of populations, it is well known that disparities-the size of the gap or inequality in social and economic status between groups within a given population-greatly affect the health status of the whole. The larger the gap, the lower the health status of the overall population.

See also

- Health equityHealth equityHealth equity refers to the study of differences in the quality of health and health care across different populations....

- Health literacyHealth literacyHealth literacy is an individual's ability to read, understand and use healthcare information to make decisions and follow instructions for treatment...

- Global healthGlobal healthGlobal health is the health of populations in a global context and transcends the perspectives and concerns of individual nations. Health problems that transcend national borders or have a global political and economic impact, are often emphasized...

- Diseases of affluenceDiseases of affluenceDiseases of affluence is a term sometimes given to selected diseases and other health conditions which are commonly thought to be a result of increasing wealth in a society...

- Diseases of povertyDiseases of povertyDiseases of poverty is a term sometimes used to collectively describe diseases and health conditions that are more prevalent among the poor than among wealthier people. In many cases poverty is considered the leading risk factor or determinant for such diseases, and in some cases the diseases...

- Population healthPopulation healthPopulation health has been defined as “the health outcomes of a group of individuals, including the distribution of such outcomes within the group.” It is an approach to health that aims to improve the health of an entire population. One major step in achieving this aim is to reduce health...

- Population Health ForumPopulation Health ForumThe Population Health Forum is a group based at University of Washington in Seattle, Washington, and composed of academics, citizens, students, and activists from around North America.- Purpose and activities :...

- Hopkins Center for Health Disparities SolutionsHopkins Center for Health Disparities SolutionsThe Hopkins Center for Health Disparities Solutions , a research center within the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, was established in October 2002 with a 5-year grant from the National Center for Minority Health and Health Disparities , of the National Institutes of Health under...

- Whitehall StudyWhitehall StudyThe original Whitehall Study investigated social determinants of health, specifically the cardiorespiratory disease prevalence and mortality rates among British male civil servants between the ages of 20 and 64. The initial prospective cohort study, the Whitehall I Study, examined over 18,000...

- Center for Minority HealthCenter for Minority HealthThe Center for Minority Health , part of The University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health, was established in 1994 through a grant from the Richard King Mellon Foundation...

- Race and healthRace and healthRace and health research, often done in the United States, has found both current and historical racial differences in the frequency, treatments, and availability of treatments for several diseases. This can add up to significant group differences in variables such as life expectancy...

- Social determinants of obesitySocial determinants of obesityWhile genetic influences are important to understanding obesity, they cannot explain the current dramatic increase seen within specific countries or globally...

- Social epidemiologySocial epidemiologySocial epidemiology is defined as "The branch of epidemiology that studies the social distribution and social determinants of health," that is, "both specific features of, and pathways by which, societal conditions affect health."...

- Unnatural Causes: Is Inequality Making Us Sick?Unnatural Causes: Is Inequality Making Us Sick?Unnatural Causes: Is Inequality Making Us Sick? is a four-hour documentary series, broadcast nationally on PBS in spring 2008, that examines the role of social determinants of health in creating health inequalities/health disparities in the United States...

- Medical anthropologyMedical anthropologyMedical anthropology is an interdisciplinary field which studies "human health and disease, health care systems, and biocultural adaptation". It views humans from multidimensional and ecological perspectives...

- Medical sociologyMedical sociologyMedical sociology is the sociological analysis of medical organizations and institutions; the production of knowledges and selection of methods, the actions and interactions of healthcare professionals, and the social or cultural effects of medical practice...

- Michael MarmotMichael MarmotSir Michael Gideon Marmot is professor of Epidemiology and Public Health at University College London.- Career :Michael Marmot was born in London, England. He moved to Australia as a young child and graduated in Medicine from the University of Sydney, Australia, in 1968. He earned a MPH in 1972...

- Richard G. Wilkinson

- Dennis RaphaelDennis RaphaelDennis Raphael is a professor of Health Policy and Management at York University in Toronto. Dr. Raphael received his Ph.D. from the University of Toronto in 1975. He completed his M.Sc. in 1974 and B.Sc...

Further reading

- Raphael, D. (2010). About Canada: Health and Illness, Retrieved August, 2010, from http://www.fernwoodpublishing.ca/About-Canada-Health-and-Illness-Dennis-Raphael/

- Health Canada. (2001). The Population Health Template: Key Elements and Actions That Define A Population Health Approach. Retrieved June, 2002, from http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hppb/phdd/pdf/discussion_paper.pdf

- Raphael, D. (2008c). Public policy and population health in the USA: Why is the public health community missing in action? International Journal of Health Services, 38, 63-94.

- Social Determinants of Health: Canadian Perspectives provides the latest developments and is available at http://www.cspi.org/books/social_determinants_health Excerpts are available at http://www.policyalternatives.ca/publications/monitor/november-2008-inequality-spawns-sickness

External links

- Social Determinants of Health: The Canadian Facts

- About Canada: Health and Illness

- Unnatural Causes: Is Inequality Making Us Sick?

- Public Health Agency of Canada: What determines health? - Key Determinants

- World Health Organization: Commission on Social Determinants of Health

- Population Health Forum website

- VIDEO: Health Status Disparities in the US featuring Paula Braveman, Gregg Bloche, George Kaplan, Thomas Ricketts, Mary Lou deLeon Siantz, and David Williams

- CBC Ideas - Sick People or Sick Societies? Part 1 and Part 2