, Austrian Empire

, now Donji Kraljevec

, Croatia

– 30 March 1925 in Dornach, Switzerland

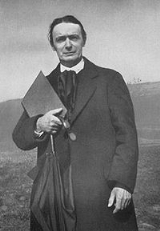

) was an Austrian

philosopher

, social reformer, architect

, and esotericist

. He gained initial recognition as a literary critic and cultural philosopher. At the beginning of the 20th century, he founded a spiritual movement, Anthroposophy

, as an esoteric philosophy growing out of European transcendentalism and with links to Theosophy

.

Steiner led this movement through several phases.

Live through deeds of love, and let others live with tolerance for their unique intentions. ![]()

Each individual is a species unto him/herself.![]()

Anthroposophy is a path of knowledge, to guide the spiritual in the human being to the spiritual in the universe... Anthroposophists are those who experience, as an essential need of life, certain questions on the nature of the human being and the universe, just as one experiences hunger and thirst.![]()

Goethe's thinking was mobile. It followed the whole growth process of the plant and followed how one plant form is a modification of the other. Goethe's thinking was not rigid with inflexible contours; it was a thinking in which the concepts continually metamorphose. Thereby his concepts became, if I may put it this way, intimately adapted to the process that plant nature itself goes through.![]()

You have no idea how unimportant is all that the teacher says or does not say on the surface, and how important what he himself is as teacher.![]()