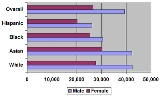

Male-female income disparity in the USA

Encyclopedia

Male–female income diference, also referred to as the "gender gap in earnings" in the United States

, and as the "gender wage gap", the "gender earnings gap" and the "gender pay gap", refers usually to the ratio of female to male median yearly earnings among full-time, year-round (FTYR) workers.

The statistic is used by government agencies and economists, and is gathered by the United States Census Bureau

as part of the Current Population Survey

.

In 2009 the median income of FTYR workers was $47,127 for men, compared to $36,278 for women. The female-to-male earnings ratio was 0.77, not statistically different from the 2008 ratio. The female-to-male earnings ratio of 0.77 means that, in 2009, female FTYR workers earned 23% less than male FTYR workers. The statistic does not take into account differences in experience, skill, occupation, education or hours worked, as long as it qualifies as full-time work. However, in 2010, the U.S. Congress Joint Economic Committee

reported that studies "always find that some portion of the wage gap is unexplained" even after controlling for measurable factors that are assumed to influence earnings. The unexplained portion of the wage gap is attributed to gender discrimination.

and the District of Columbia according to the Income, Earnings, and Poverty Data From the 2007 American Community Survey by the Census Bureau

. The national female-to-male earnings ratio was 77.5 %. In the South, five states (Maryland, North Carolina, Florida, Georgia, and Texas) and the District of Columbia had ratios higher than the national ratio, as did three states in the West (California, Arizona, and Colorado). Two states in the Northeast (Vermont and New York) had ratios higher than the national ratio. There were no states in the Midwest that had ratios higher than the national ratio. As a result, women’s earnings were closer to men’s in more states in the South and the West than in the Northeast and the Midwest.

According to an analysis of Census Bureau data released by Reach Advisors in 2008, single childless women between ages 22 and 30 were earning more than their male counterparts in most United States cities, with incomes that were 8% greater than males on average. This shift is driven by the growing ranks of women who attend colleges and move on to high-earning jobs.

In 2009, women’s weekly median earnings were higher than men’s in only four of the 108 occupations for which sufficient data were available to the Bureau of Labor Statistics

. The four occupations with higher weekly median earnings for women than men were "Other life, physical, and social science technicians" (102.4%), "bakers" (104.0%), "teacher assistants" (104.6%), and "dining room and cafeteria attendants and bartender helpers" (111.1%). The four largest gender wage gaps were found in well-paying occupations such as "Physicians and surgeons" (64.2%), "securities, commodities and financial services sales agents" (64.5%), "financial managers" (66.6%), and "other business operations specialists" (66.9%).

Men's and fathers' rights activist Warren Farrell

stated that in 2003 there were at least 39 jobs where women earned at least 5% more than men. He stated the higher pay for women over men ranged from a high of 43% higher pay for female sales engineers over their male counterparts, to an 5% higher pay for female advertising and promotions managers over their male counterparts. However, the BLS

report Highlights in Women's Earnings in 2003 showed that there were only two occupations where women's median weekly earnings exceeded men's. The two occupations were "Packers and packagers, hand" (101.4%) and "Health diagnosing and treating

practitioner support technicians" (100.5%).

In 2009 Bloomberg News reported that the sixteen women heading companies in the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index averaged earnings of $14.2 million in their latest fiscal years, 43 percent more than the male average. Bloomberg News also found that of the people who were S&P 500 CEOs in 2008, women got a 19 percent raise in 2009 while men took a 5 percent cut.

In a 2008 report titled Women's Earnings in 2008, the Bureau of Labor Statistics

reported women's median weekly earnings to be 79.9% of men's. Women earned 74.5% percent as much as men among workers 35 to 44 years old and 92.5 percent as much among 20- to 24-year-olds.

According to Andrew Beveridge, a Professor of Sociology at Queens College, between 2000 and 2005, young women in their twenties earned more than their male counterparts in some large urban centers, including Dallas (120%), New York (117%), Chicago, Boston, and Minneapolis. A major reason for this is that women have been graduating from college in larger numbers than men, and that many of those women seem to be gravitating toward major urban areas. In 2005, 53% of women in their 20s working in New York were college graduates, compared with only 38% of men of that age. Nationwide, the wages of that group of women averaged 89% of the average full-time pay for men between 2000 and 2005.

Using Current Population Survey

(CPS) data for 1979 and 1995 and controlling for education, experience, personal characteristics, parental status, city and region, occupation, industry, government employment, and part-time status, Yale University economics professor Joseph G. Altonji and the United States Secretary of Commerce

Rebecca M. Blank found that only about 27% of the gender wage gap in each year is explained by differences in such characteristics.

By looking at a very specific and detailed sample of workers (graduates of the University of Michigan Law School

) economists Robert Wood, Mary Corcoran and Paul Courant

were able to examine the wage gap while matching men and women for many other possible explanatory factors - not only occupation, age, experience, education, and time in the workforce, but also childcare, average hours worked, grades while in college, and other factors. Even after accounting for all that, women still are paid only 81.5% of what men "with similar demographic characteristics, family situations, work hours, and work experience" are paid.

Similarly, a comprehensive study by the staff of the U.S. Government Accountability Office found that the gender wage gap can only be partially explained by human capital factors and "work patterns." The GAO study, released in 2003, was based on data from 1983 through 2000 from a representative sample of Americans between the ages of 25 and 65. The researchers controlled for "work patterns," including years of work experience, education, and hours of work per year, as well as differences in industry, occupation, race, marital status, and job tenure. With controls for these variables in place, the data showed that women earned, on average, 20% less than men during the entire period 1983 to 2000. In a subsequent study, GAO found that the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and the Department of Labor “should better monitor their performance in enforcing anti-discrimination laws.”

Using CPS data, U.S. Bureau of Labor economist Stephanie Boraas and College of William & Mary economics professor William R. Rodgers III report that only 39% of the gender pay gap is explained in 1999, controlling for percent female, schooling, experience, region, SMSA size, minority status, part-time employment, marital status, union, government employment, and industry.

Using data from longitudinal studies conducted by the U.S. Department of Education, researchers Judy Goldberg Dey and Catherine Hill analyzed some 9,000 college graduates from 1992–93 and more than 10,000 from 1999-2000. The researchers controlled for workplace flexibility, ability to telecommute, as well as other several variables including occupation, industry, hours worked per week, whether employee worked multiple jobs, months at employer, and several education-related and "demographic and personal" factors, such as "marital status," "has children," and "volunteered in past year.” The study found that wage inequities start early and worsen over time. "The portion of the pay gap that remains unexplained after all other factors are taken into account is 5 percent one year after graduation and 12 percent 10 years after graduation. These unexplained gaps are evidence of discrimination, which remains a serious problem for women in the work force.”

Economists Francine Blau and Lawrence Kahn took a set of human capital variables such as education, labor market experience, and race into account and additionally controlled for occupation, industry, and unionism. While the gender wage gap was considerably smaller when all variables were taken into account, a substantial portion of the pay gap (12%) remained unexplained.

A study by John McDowell, Larry Singell and James Ziliak investigated faculty promotion on the economics profession and found that, controlling for quality of Ph.D. training, publishing productivity, major field of specialization, current placement in a distinguished department, age and post-Ph.D. experience, female economists were still significantly less likely to be promoted from assistant to associate and from associate to full professor—although there was also some evidence that women’s promotion opportunities from associate to full professor improved in the 1980s.

Economist June O'Neill, former director of the Congressional Budget Office, found an unexplained pay gap of 8% after controlling for experience, education, and number of years on the job. Furthermore, O'Neil found that among young people who have never had a child, women's earnings approach 98 percent of men's.

A 2010 study by Catalyst

, a nonprofit that works to expand opportunities for women in business, of male and female MBA graduates found that after controlling for career aspirations, parental status, years of experience, industry, and other variables, male graduates are more likely to be assigned jobs of higher rank and responsibility and earn, on average, $4,600 more than women in their first post-MBA jobs.

However, numerous studies indicate that variables such as hours worked account for only part of the gender pay gap and that the pay gap shrinks but does not disappear after controlling for all human capital variable which are known to affect pay. Moreover, Gary Becker

argues that the traditional division of labor in the family disadvantages women in the labor market as women devote substantially more time and effort to housework and have less time and effort available for performing market work. The OECD (2002) found that women work fewer hours because in the present circumstances the "responsibilities for child-rearing and other unpaid household work are still unequally shared among partners."

In 2008, a group of researchers examined occupational segregation and its implications for the salaries assigned to male- and female-typed jobs. They investigated whether participants would assign different pay to 3 types of jobs wherein the actual responsibilities and duties carried out by men and women were the same, but the job was situated in either a traditionally masculine or traditionally feminine domain. The researchers found statistically significant pay differentials between jobs defined as "male" and "female," which suggest that gender-based discrimination, arising from occupational stereotyping and the devaluation of the work typically done by women, influences salary allocation. The results fit with contemporary theorizing about gender-based discrimination.

A study showed that if a white woman in an all-male workplace moved to an all-female workplace, she would lose 7% of her wages. If a black woman did the same thing, she would lose 19% of her wages. Another study calculated that if female-dominated jobs did not pay lower wages, women's median hourly pay nationwide would go up 13.2% (men's pay would go up 1.1%, due to raises for men working in "women's jobs").

Numerous studies indicate that the pay gap shrinks but does not disappear after controlling for occupation and a host of other human capital variables.

A 2009 study of high school valedictorian

s in the U.S. found that female valedictorians were planning to have careers that had a median salary of $74,608, whereas male valedictorians were planning to have careers with a median salary of $97,734. As to why the females were less likely than the males to choose high paying careers such as surgeon and engineer, the New York Times article quoted the researcher as saying, "The typical reason is that they are worried about combining family and career one day in the future."

However, Jerry A. Jacobs

and Ronnie Steinberg, as well as Jennifer Glass separately, found that male-dominated jobs actually have more flexibility and autonomy than female-dominated jobs, thus allowing a person, for example, to more easily leave work to tend to a sick child. Similarly, Heather Boushey

stated that men actually have more access to workplace flexibility and that it is a "myth that women choose less-paying occupations because they provide flexibility to better manage work and family."

Economists Blau and Kahn and Wood et al. separately argue that "free choice" factors, while significant, have been shown in studies to leave large portions of the gender earnings gap unexplained.

Studies by Michael Conway et al., David Wagner and Joseph Berger, John Williams and Deborah Best, and Susan Fiske

et al. found widely shared cultural beliefs that men are more socially valued and more competent than women at most things, as well as specific assumptions that men are better at some particular tasks (e.g., math, mechanical tasks) while women are better at others (e.g., nurturing tasks). Shelley Correll, Michael Lovaglia, Margaret Shih et al., and Claude Steele show that these gender status beliefs affect the assessments people make of their own competence at career-relevant tasks. Correll found that specific stereotypes (e.g., women have lower mathematical ability) affect women’s and men’s perceptions of their abilities (e.g., in math and science) such that men assess their own task ability higher than women performing at the same level. These “biased self-assessments” shape men and women’s educational and career decisions.

Similarly, the OECD states that women's labour market behaviour "is influenced by learned cultural and social values that may be thought to discriminate against women (and sometimes against men) by stereotyping certain work and life styles as “male” or “female”." Further, the OECD argues that women's educational choices "may be dictated, at least in part, by their expectations

that [certain] types of employment opportunities are not available to them, as well as by gender stereotypes that are prevalent in society."

argued that discrimination by employers tends to steer women into lower-paying occupations and men into higher-paying occupations.

Warren Farrell

has stated that the pay gap can no longer be attributed to large-scale discrimination against women. He has also stated that men earn more because they enter higher-paying fields. Farrell's data was critiqued by economist Barbara Bergmann

.

For instance, David R. Hekman

and colleagues (2009) found that men receive significantly higher customer satisfaction scores than equally well-performing women. Hekman et al. (2009) found that customers who viewed videos featuring a female and a male actor playing the role of an employee helping a customer were 19% more satisfied with the male employee's performance and also were more satisfied with the store's cleanliness and appearance. This was despite the fact that the actors performed identically, read the same script, and were in exactly the same location with identical camera angles and lighting. Moreover, 38% of the customers were women, indicating that even women and minority raters are susceptible to systematic gender biases. In a second study, they found that male doctors were rated as more approachable and competent than equally well performing female doctors. They interpret their findings to suggest that customer ratings tend to be inconsistent with objective indicators of performance and should not be uncritically used to determine pay and promotion opportunities. They contend that in addition to addressing factors that cause bias in customer ratings, organizations should take steps to minimize the potential adverse impact of customer biases on female employees’ careers.

Similarly, a study (2000) conducted by economic experts Claudia Goldin

from Harvard University

and Cecilia Rouse

from Princeton University

shows that when evaluators of applicants could see the applicant’s gender they were more likely to select men. When the applicants gender could not be observed, the number of women hired significantly increased. David Neumark

, a Professor of Economics at the University of California, Irvine

, and colleagues (1996) found statistically significant evidence of sex discrimination against women in hiring. In an audit study, matched pairs of male and female pseudo-job seekers were given identical résumés and sent to apply for jobs as waiters and waitresses at the same set of restaurants. In high priced restaurants, a female applicant’s probability of getting an interview was 35 percentage points lower than a male’s and her probability of getting a job offer was 40 percentage points lower. Additional evidence suggests that customer biases in favor of men partly underlie the hiring discrimination. According to Neumark, these hiring patterns appear to have implications for sex differences in earnings, as informal survey evidence indicates that earnings are higher in high-price restaurants.

cites men's and fathers' rights activists who contend that women do not allow men to take on paternal and domestic responsibilities. Many Western countries have some form of paternity leave to attempt to level the playing field in this regard. However, even in relatively gender-equal countries like Sweden, where parents are given 16 months of paid parental leave irrespective of gender, fathers take on average only 20% of the 16 months of paid parental and choose to transfer their days to their partner. In addition to maternity leave, Walter Block

and Walter E. Williams

have argued that marriage in and of itself, not maternity leave, in general will leave females with more household labor than the males. The Bureau of Labor Statistics found that married women earn 75.5% as much as married men while women who have never married earn 94.2% of their unmarried male counterparts' earnings.

found that women in science and engineering are hindered by bias and "outmoded institutional structures" in academia. The report Beyond Bias and Barriers

says that extensive previous research showed a pattern of unconscious but pervasive bias, "arbitrary and subjective" evaluation processes and a work environment in which "anyone lacking the work and family support traditionally provided by a ‘wife’ is at a serious disadvantage." Similarly, a 1999 report on faculty at MIT finds evidence of differential treatment of senior women and points out that it may encompass not simply differences in salary but also in space, awards, resources and responses to outside offers, "with women receiving less despite professional accomplishments equal to those of their male colleagues." However, the MIT study was later debunked as "junk science"--its conclusions were erroneous and politically motivated (Kleinfeld, 1999: MIT tarnishes its reputation with gender junk science; Kleinfeld, 2002: Exposing Junk Science. com: The Case of the MIT" Study" on the Status of Women).

Research finds that work by men is often subjectively seen as higher-quality than objectively equal or better work by women compared to how an actual scientific review panel measured scientific competence when deciding on research grants. The results showed that female scientists needed to be at least twice as accomplished as their male counterparts to receive equal credit and that among grant applicants men have statistically significant greater odds of receiving grants than equally qualified women.

Alice H. Eagly and Steven J. Karau (2002) argue that "perceived incongruity between the female gender role and leadership roles leads to two forms of prejudice: (a) perceiving women less favorably than men as potential occupants of leadership roles and (b) evaluating behavior that fulfills the prescriptions of a leader role less favorably when it is enacted by a woman. One consequence is that attitudes are less positive toward female than male leaders and potential leaders. Other consequences are that it is more difficult for women to become leaders and to achieve success in leadership roles." Moreover, research suggests that when women are acknowledged to have been successful, they are less liked and more personally derogated than equivalently successful men. Assertive women who display masculine, agentic traits are viewed as violating prescriptions of feminine niceness and are penalized for violating the status order.

Stanford University

professor Shelley Correll and colleagues (2007) sent out more than 1,200 fictitious résumés to employers in a large Northeastern city, and found that female applicants with children were significantly less likely to get hired and if hired would be paid a lower salary than male applicants with children. This despite the fact that the qualification, workplace performances and other relevant characteristics of the fictitious job applicants were held constant and only their parental status varied. Mothers were penalized on a host of measures, including perceived competence and recommended starting salary. Men were not penalized for, and sometimes benefited from, being a parent. In a subsequent audit study, Correll et al. found that actual employers discriminate against mothers when making evaluations that affect hiring, promotion, and salary decisions, but not against fathers. The researchers review results from other studies and argue that the motherhood role exists in tension with the cultural understandings of the "ideal worker" role and this leads evaluators to expect mothers to be less competent and less committed to their job. Fathers do not experience these types of workplace disadvantages as understandings of what it means to be a good father are not seen as incompatible with understandings of what it means to be a good worker.

Similarly, Fuegen et al. found that when evaluators rated fictitious applicants for an attorney position, female applicants with children were held to a higher standard than female applicants without children. Fathers were actually held to a significantly lower standard than male non-parents. Cuddy, Fiske, and Glick show that describing a consultant as a mother leads evaluators to rate her as less competent than when she is described as not having children.

Research has also shown there to be a "marriage premium" for men with labor economists frequently reporting that married men earn higher wages than unmarried men, and speculating that this may be attributable to one or more of the following causes: (1) more productive men marry at greater rates (attributing the marriage premium to selection bias), (2) men become more productive following marriage (due to labor market specialization by men and domestic specialization by women), or (3) employers favor married men. Lincoln (2008) found no support for the specialization hypothesis among full-time employed workers. Some studies have suggested this premium is greater for men with children while others have shown fatherhood to have no effect on wages one way or the other.

Perceptions of wage entitlement differ between women and men such that men are more likely to feel worthy of higher pay. while women's sense of wage entitlement is depressed. Women's beliefs about their relatively lower worth and their depressed wage entitlement reflects their lower social status such that when women's status is raised, their wage entitlement raises as well. However, gender-related status manipulation has no impact on men's elevated wage entitlement. Even when men's status is lowered on a specific task (e.g., by telling them that women typically outperform men on this task), men do not reduce their self-pay and respond with elevated projections of their own competence. The usual pattern whereby men assign themselves more pay than women for comparable work might explain why men tend to initiate negotiations more than women.

In a study by psychologist Melissa Williams et al., published in 2010, study participants were given pairs of male and female first names, and asked to estimate their salaries. Men and to a lesser degree women estimated significantly higher salaries for men than women, replicating previous findings. In a subsequent study, participants were placed in the role of employer and were asked to judge what newly hired men and women deserve to earn. The researchers found that men and to a lesser extent women assign higher salaries to men than women based on automatic stereotypic associations. The researchers argue that observations of men as higher earners than women has led to a stereotype that associates men (more than women) with wealth, and that this stereotype itself may serve to perpetuate the wage gap at both conscious and nonconscious levels. For example, a male-wealth stereotype may influence an employer’s initial salary offer to a male job candidate, or a female college graduate’s intuitive sense about what salary she can appropriately ask for at her first job.

Harvard University

professor Hannah Riley and Linda Babcock conducted a study, published in 2007, that found that women are penalized when they try to negotiate starting salaries. Male evaluators tended to rule against women who negotiated but were less likely to penalize men; female evaluators tended to penalize both men and women who negotiated, and preferred applicants who did not ask for more. The study also showed that women who applied for jobs were not as likely to be hired by male managers if they tried to ask for more money, while men who asked for a higher salary were not negatively affected.

Barry Gerhart and Sara Rymes (1991) investigated the salary negotiating behaviors and starting salary outcomes of graduating MBA students and found that women did not negotiate less than men. However, women did obtain lower monetary returns from negotiation. Over the course of a career, the accumulation of such differences may be substantial, according to the researchers.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics

investigated job traits that are associated with wage premiums, and stated: "The duties most highly valued by the marketplace are generally cognitive or supervisory in nature. Job attributes relating to interpersonal relationships do not seem to affect wages, nor do the attributes of physically demanding or dangerous jobs." Economists Peter Dorman and Paul Hagstrom (1998) state that "The theoretical case for wage compensation for risk is plausible but hardly certain. If workers have utility functions in which the expected likelihood and cost of occupational hazards enter as arguments, if they are fully informed of risks, if firms possess sufficient information on worker expectations and preferences (directly or through revealed preferences), if safety is costly to provide and not a public good, and if risk is fully transacted in anonymous, perfectly competitive labor markets, then workers will receive wage premia that exactly offset the disutility of assuming greater risk of injury or death. Of course, none of these assumptions applies in full and if one or more of them is sufficiently at variance with the real world, actual compensation may be less than utility-offsetting, nonexistent, or even negative - a combination of low pay and poor working conditions."

, the gender pay gap jeopardizes women's retirement security. Of the multiple sources of income Americans rely on later in life, many are directly linked to a worker’s earnings over his or her career. These include Social Security

benefits, based on lifetime earnings, and defined benefit pension

distributions that are typically calculated using a formula based on a worker’s tenure and salary during peak‐earnings years. The persistent gender pay gap leaves women with less income from these sources than men. For example, older women’s Social Security benefits are 71 % of older men’s benefits ($11,057 for women versus $15,557 for men in 2009). Incomes from public and private pensions based on women’s own work were just 60 % and 48 % of men’s pension incomes, respectively.

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

, and as the "gender wage gap", the "gender earnings gap" and the "gender pay gap", refers usually to the ratio of female to male median yearly earnings among full-time, year-round (FTYR) workers.

The statistic is used by government agencies and economists, and is gathered by the United States Census Bureau

United States Census Bureau

The United States Census Bureau is the government agency that is responsible for the United States Census. It also gathers other national demographic and economic data...

as part of the Current Population Survey

Current Population Survey

The Current Population Survey is a statistical survey conducted by the United States Census Bureau for the Bureau of Labor Statistics . The BLS uses the data to provide a monthly report on the Employment Situation. This report provides estimates of the number of unemployed people in the United...

.

In 2009 the median income of FTYR workers was $47,127 for men, compared to $36,278 for women. The female-to-male earnings ratio was 0.77, not statistically different from the 2008 ratio. The female-to-male earnings ratio of 0.77 means that, in 2009, female FTYR workers earned 23% less than male FTYR workers. The statistic does not take into account differences in experience, skill, occupation, education or hours worked, as long as it qualifies as full-time work. However, in 2010, the U.S. Congress Joint Economic Committee

United States Congress Joint Economic Committee

The Joint Economic Committee is one of four standing joint committees of the U.S. Congress. The committee was established as a part of the Employment Act of 1946, which deemed the committee responsible for reporting the current economic condition of the United States and for making suggestions...

reported that studies "always find that some portion of the wage gap is unexplained" even after controlling for measurable factors that are assumed to influence earnings. The unexplained portion of the wage gap is attributed to gender discrimination.

Gender pay gap statistics

Women's median yearly earnings relative to men's rose rapidly from 1980 to 1990 (from 60.2% to 71.6%), and less rapidly from 1990 to 2000 (from 71.6% to 73.7%) and from 2000 to 2009 (from 73.7% to 77.0%).By state

In 2007, women’s earnings were lower than men's earnings in all statesU.S. state

A U.S. state is any one of the 50 federated states of the United States of America that share sovereignty with the federal government. Because of this shared sovereignty, an American is a citizen both of the federal entity and of his or her state of domicile. Four states use the official title of...

and the District of Columbia according to the Income, Earnings, and Poverty Data From the 2007 American Community Survey by the Census Bureau

United States Census Bureau

The United States Census Bureau is the government agency that is responsible for the United States Census. It also gathers other national demographic and economic data...

. The national female-to-male earnings ratio was 77.5 %. In the South, five states (Maryland, North Carolina, Florida, Georgia, and Texas) and the District of Columbia had ratios higher than the national ratio, as did three states in the West (California, Arizona, and Colorado). Two states in the Northeast (Vermont and New York) had ratios higher than the national ratio. There were no states in the Midwest that had ratios higher than the national ratio. As a result, women’s earnings were closer to men’s in more states in the South and the West than in the Northeast and the Midwest.

According to an analysis of Census Bureau data released by Reach Advisors in 2008, single childless women between ages 22 and 30 were earning more than their male counterparts in most United States cities, with incomes that were 8% greater than males on average. This shift is driven by the growing ranks of women who attend colleges and move on to high-earning jobs.

By industry and occupation

Women's median weekly earnings were lower than men's median weekly earnings in all industries in 2009. The industry with the largest gender pay gap was financial activities. Median weekly earnings of women employed in financial activities were 70.5% of men's median weekly earnings in that industry. Construction was the industry with the smallest gender pay gap (92.2%).In 2009, women’s weekly median earnings were higher than men’s in only four of the 108 occupations for which sufficient data were available to the Bureau of Labor Statistics

Bureau of Labor Statistics

The Bureau of Labor Statistics is a unit of the United States Department of Labor. It is the principal fact-finding agency for the U.S. government in the broad field of labor economics and statistics. The BLS is a governmental statistical agency that collects, processes, analyzes, and...

. The four occupations with higher weekly median earnings for women than men were "Other life, physical, and social science technicians" (102.4%), "bakers" (104.0%), "teacher assistants" (104.6%), and "dining room and cafeteria attendants and bartender helpers" (111.1%). The four largest gender wage gaps were found in well-paying occupations such as "Physicians and surgeons" (64.2%), "securities, commodities and financial services sales agents" (64.5%), "financial managers" (66.6%), and "other business operations specialists" (66.9%).

Men's and fathers' rights activist Warren Farrell

Warren Farrell

Warren Farrell is an American author of seven books on men's and women's issues. His books cover twelve fields: history, law, sociology and politics ; couples’ communication ; economic and career issues ; child psychology and child custody ; and...

stated that in 2003 there were at least 39 jobs where women earned at least 5% more than men. He stated the higher pay for women over men ranged from a high of 43% higher pay for female sales engineers over their male counterparts, to an 5% higher pay for female advertising and promotions managers over their male counterparts. However, the BLS

Bureau of Labor Statistics

The Bureau of Labor Statistics is a unit of the United States Department of Labor. It is the principal fact-finding agency for the U.S. government in the broad field of labor economics and statistics. The BLS is a governmental statistical agency that collects, processes, analyzes, and...

report Highlights in Women's Earnings in 2003 showed that there were only two occupations where women's median weekly earnings exceeded men's. The two occupations were "Packers and packagers, hand" (101.4%) and "Health diagnosing and treating

practitioner support technicians" (100.5%).

In 2009 Bloomberg News reported that the sixteen women heading companies in the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index averaged earnings of $14.2 million in their latest fiscal years, 43 percent more than the male average. Bloomberg News also found that of the people who were S&P 500 CEOs in 2008, women got a 19 percent raise in 2009 while men took a 5 percent cut.

By age

The earnings difference between women and men varies with age, with younger women more closely approaching pay equity than older women.In a 2008 report titled Women's Earnings in 2008, the Bureau of Labor Statistics

Bureau of Labor Statistics

The Bureau of Labor Statistics is a unit of the United States Department of Labor. It is the principal fact-finding agency for the U.S. government in the broad field of labor economics and statistics. The BLS is a governmental statistical agency that collects, processes, analyzes, and...

reported women's median weekly earnings to be 79.9% of men's. Women earned 74.5% percent as much as men among workers 35 to 44 years old and 92.5 percent as much among 20- to 24-year-olds.

According to Andrew Beveridge, a Professor of Sociology at Queens College, between 2000 and 2005, young women in their twenties earned more than their male counterparts in some large urban centers, including Dallas (120%), New York (117%), Chicago, Boston, and Minneapolis. A major reason for this is that women have been graduating from college in larger numbers than men, and that many of those women seem to be gravitating toward major urban areas. In 2005, 53% of women in their 20s working in New York were college graduates, compared with only 38% of men of that age. Nationwide, the wages of that group of women averaged 89% of the average full-time pay for men between 2000 and 2005.

Explaining the gender pay gap

Any given raw wage gap can be decomposed into an explained part due to differences in characteristics such as education, hours worked, work experience, and occupation, and an unexplained part which is typically attributed to discrimination. The U.S. Congress Joint Economic Committee shows that “as explained inequities decrease, the unexplained pay gap remains unchanged. Cornell University economists Francine Blau and Lawrence Kahn stated that while the overall size of the wage gap has decreased somewhat over time, the proportion of the gap that is unexplained by human capital variables is increasing.Using Current Population Survey

Current Population Survey

The Current Population Survey is a statistical survey conducted by the United States Census Bureau for the Bureau of Labor Statistics . The BLS uses the data to provide a monthly report on the Employment Situation. This report provides estimates of the number of unemployed people in the United...

(CPS) data for 1979 and 1995 and controlling for education, experience, personal characteristics, parental status, city and region, occupation, industry, government employment, and part-time status, Yale University economics professor Joseph G. Altonji and the United States Secretary of Commerce

United States Secretary of Commerce

The United States Secretary of Commerce is the head of the United States Department of Commerce concerned with business and industry; the Department states its mission to be "to foster, promote, and develop the foreign and domestic commerce"...

Rebecca M. Blank found that only about 27% of the gender wage gap in each year is explained by differences in such characteristics.

By looking at a very specific and detailed sample of workers (graduates of the University of Michigan Law School

University of Michigan Law School

The University of Michigan Law School is the law school of the University of Michigan, in Ann Arbor. Founded in 1859, the school has an enrollment of about 1,200 students, most of whom are seeking Juris Doctor or Master of Laws degrees, although the school also offers a Doctor of Juridical...

) economists Robert Wood, Mary Corcoran and Paul Courant

Paul Courant

Paul Courant is an American economist. He is currently serving as University Librarian and Dean of Libraries at the University of Michigan. He is an expert in public goods, and his recent research focuses on the economics of universities, the economics of libraries and archives, and the impact of...

were able to examine the wage gap while matching men and women for many other possible explanatory factors - not only occupation, age, experience, education, and time in the workforce, but also childcare, average hours worked, grades while in college, and other factors. Even after accounting for all that, women still are paid only 81.5% of what men "with similar demographic characteristics, family situations, work hours, and work experience" are paid.

Similarly, a comprehensive study by the staff of the U.S. Government Accountability Office found that the gender wage gap can only be partially explained by human capital factors and "work patterns." The GAO study, released in 2003, was based on data from 1983 through 2000 from a representative sample of Americans between the ages of 25 and 65. The researchers controlled for "work patterns," including years of work experience, education, and hours of work per year, as well as differences in industry, occupation, race, marital status, and job tenure. With controls for these variables in place, the data showed that women earned, on average, 20% less than men during the entire period 1983 to 2000. In a subsequent study, GAO found that the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and the Department of Labor “should better monitor their performance in enforcing anti-discrimination laws.”

Using CPS data, U.S. Bureau of Labor economist Stephanie Boraas and College of William & Mary economics professor William R. Rodgers III report that only 39% of the gender pay gap is explained in 1999, controlling for percent female, schooling, experience, region, SMSA size, minority status, part-time employment, marital status, union, government employment, and industry.

Using data from longitudinal studies conducted by the U.S. Department of Education, researchers Judy Goldberg Dey and Catherine Hill analyzed some 9,000 college graduates from 1992–93 and more than 10,000 from 1999-2000. The researchers controlled for workplace flexibility, ability to telecommute, as well as other several variables including occupation, industry, hours worked per week, whether employee worked multiple jobs, months at employer, and several education-related and "demographic and personal" factors, such as "marital status," "has children," and "volunteered in past year.” The study found that wage inequities start early and worsen over time. "The portion of the pay gap that remains unexplained after all other factors are taken into account is 5 percent one year after graduation and 12 percent 10 years after graduation. These unexplained gaps are evidence of discrimination, which remains a serious problem for women in the work force.”

Economists Francine Blau and Lawrence Kahn took a set of human capital variables such as education, labor market experience, and race into account and additionally controlled for occupation, industry, and unionism. While the gender wage gap was considerably smaller when all variables were taken into account, a substantial portion of the pay gap (12%) remained unexplained.

A study by John McDowell, Larry Singell and James Ziliak investigated faculty promotion on the economics profession and found that, controlling for quality of Ph.D. training, publishing productivity, major field of specialization, current placement in a distinguished department, age and post-Ph.D. experience, female economists were still significantly less likely to be promoted from assistant to associate and from associate to full professor—although there was also some evidence that women’s promotion opportunities from associate to full professor improved in the 1980s.

Economist June O'Neill, former director of the Congressional Budget Office, found an unexplained pay gap of 8% after controlling for experience, education, and number of years on the job. Furthermore, O'Neil found that among young people who have never had a child, women's earnings approach 98 percent of men's.

A 2010 study by Catalyst

Catalyst (nonprofit organization)

Catalyst, Inc. is a nonprofit organization that promotes inclusive workplaces for women. It was founded in 1962 by feminist, writer, and advocate Felice Schwartz. Sheila Wellington served as president of Catalyst following Schwartz for ten years...

, a nonprofit that works to expand opportunities for women in business, of male and female MBA graduates found that after controlling for career aspirations, parental status, years of experience, industry, and other variables, male graduates are more likely to be assigned jobs of higher rank and responsibility and earn, on average, $4,600 more than women in their first post-MBA jobs.

Hours worked

In the book Biology at Work: Rethinking Sexual Equality, Browne writes: "Because of the sex differences in hours worked, the hourly earnings gap [...] is a better indicator of the sexual disparity in earnings than the annual figure. Even the hourly earnings ratio does not completely capture the effects of sex differences in hours, however, because employees who work more hours also tend to earn more per hour."However, numerous studies indicate that variables such as hours worked account for only part of the gender pay gap and that the pay gap shrinks but does not disappear after controlling for all human capital variable which are known to affect pay. Moreover, Gary Becker

Gary Becker

Gary Stanley Becker is an American economist. He is a professor of economics, sociology at the University of Chicago and a professor at the Booth School of Business. He was awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 1992, and received the United States' Presidential Medal of Freedom...

argues that the traditional division of labor in the family disadvantages women in the labor market as women devote substantially more time and effort to housework and have less time and effort available for performing market work. The OECD (2002) found that women work fewer hours because in the present circumstances the "responsibilities for child-rearing and other unpaid household work are still unequally shared among partners."

Occupational segregation

Occupational segregation refers to the way that some jobs (such as truck driver) are dominated by men, and other jobs (such as child care worker) are dominated by women. Considerable research suggests that predominantly female occupations pay less, even controlling for individual and workplace characteristics. Economists Blau and Kahn stated that women's pay compared to men's had improved because of a decrease in occupational segregation. They also argued that the gender wage difference will decline modestly and that the extent of discrimination against women in the labor market seems to be decreasing.In 2008, a group of researchers examined occupational segregation and its implications for the salaries assigned to male- and female-typed jobs. They investigated whether participants would assign different pay to 3 types of jobs wherein the actual responsibilities and duties carried out by men and women were the same, but the job was situated in either a traditionally masculine or traditionally feminine domain. The researchers found statistically significant pay differentials between jobs defined as "male" and "female," which suggest that gender-based discrimination, arising from occupational stereotyping and the devaluation of the work typically done by women, influences salary allocation. The results fit with contemporary theorizing about gender-based discrimination.

A study showed that if a white woman in an all-male workplace moved to an all-female workplace, she would lose 7% of her wages. If a black woman did the same thing, she would lose 19% of her wages. Another study calculated that if female-dominated jobs did not pay lower wages, women's median hourly pay nationwide would go up 13.2% (men's pay would go up 1.1%, due to raises for men working in "women's jobs").

Numerous studies indicate that the pay gap shrinks but does not disappear after controlling for occupation and a host of other human capital variables.

Workplace flexibility

It has been suggested that women choose less-paying occupations because they provide flexibility to better manage work and family.A 2009 study of high school valedictorian

Valedictorian

Valedictorian is an academic title conferred upon the student who delivers the closing or farewell statement at a graduation ceremony. Usually, the valedictorian is the highest ranked student among those graduating from an educational institution...

s in the U.S. found that female valedictorians were planning to have careers that had a median salary of $74,608, whereas male valedictorians were planning to have careers with a median salary of $97,734. As to why the females were less likely than the males to choose high paying careers such as surgeon and engineer, the New York Times article quoted the researcher as saying, "The typical reason is that they are worried about combining family and career one day in the future."

However, Jerry A. Jacobs

Jerry A. Jacobs

Jerry A. Jacobs is an American sociologist noted for his work on women and work. He is professor of sociology at the University of Pennsylvania and an affiliate of the Population Studies Center, the Graduate School of Education, the Women’s Studies Program, and the Leonard Davis Institute for...

and Ronnie Steinberg, as well as Jennifer Glass separately, found that male-dominated jobs actually have more flexibility and autonomy than female-dominated jobs, thus allowing a person, for example, to more easily leave work to tend to a sick child. Similarly, Heather Boushey

Heather Boushey

Heather Marie Boushey is a senior economist at the Center for American Progress.-Life and career:Boushey was born in Seattle and grew up in Mukilteo, Washington. She received her Ph.D. in Economics from the New School for Social Research and her B.A...

stated that men actually have more access to workplace flexibility and that it is a "myth that women choose less-paying occupations because they provide flexibility to better manage work and family."

Economists Blau and Kahn and Wood et al. separately argue that "free choice" factors, while significant, have been shown in studies to leave large portions of the gender earnings gap unexplained.

Gender stereotypes

Research suggests that gender stereotypes may be the driving force behind occupational segregation because they influence men and women’s educational and career decisions.Studies by Michael Conway et al., David Wagner and Joseph Berger, John Williams and Deborah Best, and Susan Fiske

Susan Fiske

Susan Tufts Fiske is Eugene Higgins Professor of Psychology at Princeton University's Department of Psychology. She is a social psychologist known for her work on social cognition, stereotypes, and prejudice...

et al. found widely shared cultural beliefs that men are more socially valued and more competent than women at most things, as well as specific assumptions that men are better at some particular tasks (e.g., math, mechanical tasks) while women are better at others (e.g., nurturing tasks). Shelley Correll, Michael Lovaglia, Margaret Shih et al., and Claude Steele show that these gender status beliefs affect the assessments people make of their own competence at career-relevant tasks. Correll found that specific stereotypes (e.g., women have lower mathematical ability) affect women’s and men’s perceptions of their abilities (e.g., in math and science) such that men assess their own task ability higher than women performing at the same level. These “biased self-assessments” shape men and women’s educational and career decisions.

Similarly, the OECD states that women's labour market behaviour "is influenced by learned cultural and social values that may be thought to discriminate against women (and sometimes against men) by stereotyping certain work and life styles as “male” or “female”." Further, the OECD argues that women's educational choices "may be dictated, at least in part, by their expectations

that [certain] types of employment opportunities are not available to them, as well as by gender stereotypes that are prevalent in society."

Direct discrimination

Economist David NeumarkDavid Neumark

David Neumark is an American economist and a Professor of Economics at the University of California, Irvine.- Early years :...

argued that discrimination by employers tends to steer women into lower-paying occupations and men into higher-paying occupations.

Warren Farrell

Warren Farrell

Warren Farrell is an American author of seven books on men's and women's issues. His books cover twelve fields: history, law, sociology and politics ; couples’ communication ; economic and career issues ; child psychology and child custody ; and...

has stated that the pay gap can no longer be attributed to large-scale discrimination against women. He has also stated that men earn more because they enter higher-paying fields. Farrell's data was critiqued by economist Barbara Bergmann

Barbara Bergmann

Barbara Bergmann is a forerunner in feminist economics with a passion for social policy and equality, especially relating to discrimination on account of race or sex. Her work covers many topics from childcare and women’s issues to poverty and Social Security...

.

Bias favoring men

Several authors suggest that members of low-status groups (i.e. women, racial minorities) are subject to negative stereotypes and attributes concerning their work-related competences. Similarly, studies suggest that members of high-status groups (i.e., men, whites) are more likely to receive favorable evaluations about their competence, normality, and legitimacy.For instance, David R. Hekman

David R. Hekman

David R. Hekman is an assistant professor of management at the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee.- Early life and education :A Michigan native, Hekman received his Bachelor of Business Administration in 2000 at Grand Valley State University, where he was voted "Outstanding Finance Student of the...

and colleagues (2009) found that men receive significantly higher customer satisfaction scores than equally well-performing women. Hekman et al. (2009) found that customers who viewed videos featuring a female and a male actor playing the role of an employee helping a customer were 19% more satisfied with the male employee's performance and also were more satisfied with the store's cleanliness and appearance. This was despite the fact that the actors performed identically, read the same script, and were in exactly the same location with identical camera angles and lighting. Moreover, 38% of the customers were women, indicating that even women and minority raters are susceptible to systematic gender biases. In a second study, they found that male doctors were rated as more approachable and competent than equally well performing female doctors. They interpret their findings to suggest that customer ratings tend to be inconsistent with objective indicators of performance and should not be uncritically used to determine pay and promotion opportunities. They contend that in addition to addressing factors that cause bias in customer ratings, organizations should take steps to minimize the potential adverse impact of customer biases on female employees’ careers.

Similarly, a study (2000) conducted by economic experts Claudia Goldin

Claudia Goldin

Claudia Goldin is an American economist and Henry Lee Professor of Economics at Harvard University.Goldin is a director of the Development of the American Economy Program, and is a research associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research , located in Cambridge, Massachusetts...

from Harvard University

Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League university located in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States, established in 1636 by the Massachusetts legislature. Harvard is the oldest institution of higher learning in the United States and the first corporation chartered in the country...

and Cecilia Rouse

Cecilia Rouse

Cecilia Elena Rouse , is an American economist and the Theodore A. Wells '29 Professor of Economics and Public Affairs at Princeton University. On March 20, 2009 she was formally confirmed as a member of President Barack Obama's Council of Economic Advisers; she returned to Princeton March 1,...

from Princeton University

Princeton University

Princeton University is a private research university located in Princeton, New Jersey, United States. The school is one of the eight universities of the Ivy League, and is one of the nine Colonial Colleges founded before the American Revolution....

shows that when evaluators of applicants could see the applicant’s gender they were more likely to select men. When the applicants gender could not be observed, the number of women hired significantly increased. David Neumark

David Neumark

David Neumark is an American economist and a Professor of Economics at the University of California, Irvine.- Early years :...

, a Professor of Economics at the University of California, Irvine

University of California, Irvine

The University of California, Irvine , founded in 1965, is one of the ten campuses of the University of California, located in Irvine, California, USA...

, and colleagues (1996) found statistically significant evidence of sex discrimination against women in hiring. In an audit study, matched pairs of male and female pseudo-job seekers were given identical résumés and sent to apply for jobs as waiters and waitresses at the same set of restaurants. In high priced restaurants, a female applicant’s probability of getting an interview was 35 percentage points lower than a male’s and her probability of getting a job offer was 40 percentage points lower. Additional evidence suggests that customer biases in favor of men partly underlie the hiring discrimination. According to Neumark, these hiring patterns appear to have implications for sex differences in earnings, as informal survey evidence indicates that earnings are higher in high-price restaurants.

Maternity leave

The economic risk and resulting costs of a woman possibly leaving jobs for a period of time or indefinitely to nurse a baby is cited by many to be a reason why women are less common in the higher paying occupations such as CEO positions and upper management. It is much easier for a man to be hired in these higher prestige jobs than to risk losing a female job holder. Thomas Sowell argued in his 1984 book Civil Rights that most of pay gap is based on marital status, not a “glass ceiling” discrimination. Earnings for men and women of the same basic description (education, jobs, hours worked, marital status) were essentially equal. That result would not be predicted under explanatory theories of “sexism”. However, it can be seen as a symptom of the unequal contributions made by each partner to child raising. Cathy YoungCathy Young

Cathy Young is a Russian American journalist and writer whose books and articles, as well as columns which appear in the libertarian monthly Reason, and also weekly in The Boston Globe, primarily espouse equality feminism and libertarianism.-Life and Career:Born in Moscow, the capital of what was...

cites men's and fathers' rights activists who contend that women do not allow men to take on paternal and domestic responsibilities. Many Western countries have some form of paternity leave to attempt to level the playing field in this regard. However, even in relatively gender-equal countries like Sweden, where parents are given 16 months of paid parental leave irrespective of gender, fathers take on average only 20% of the 16 months of paid parental and choose to transfer their days to their partner. In addition to maternity leave, Walter Block

Walter Block

Walter Edward Block is a free market economist and anarcho-capitalist associated with the Austrian School of economics.-Personal history and education:...

and Walter E. Williams

Walter E. Williams

Walter E. Williams, is an American economist, commentator, and academic. He is the John M. Olin Distinguished Professor of Economics at George Mason University, as well as a syndicated columnist and author known for his libertarian views.- Early life and education :Williams family during childhood...

have argued that marriage in and of itself, not maternity leave, in general will leave females with more household labor than the males. The Bureau of Labor Statistics found that married women earn 75.5% as much as married men while women who have never married earn 94.2% of their unmarried male counterparts' earnings.

Barriers in science

In 2006, the United States National Academy of SciencesUnited States National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences is a corporation in the United States whose members serve pro bono as "advisers to the nation on science, engineering, and medicine." As a national academy, new members of the organization are elected annually by current members, based on their distinguished and...

found that women in science and engineering are hindered by bias and "outmoded institutional structures" in academia. The report Beyond Bias and Barriers

Beyond Bias and Barriers

Beyond Bias and Barriers: Fulfilling the Potential of Women in Academic Science and Engineering is a major report about the status of women in science from the United States National Academy of Sciences...

says that extensive previous research showed a pattern of unconscious but pervasive bias, "arbitrary and subjective" evaluation processes and a work environment in which "anyone lacking the work and family support traditionally provided by a ‘wife’ is at a serious disadvantage." Similarly, a 1999 report on faculty at MIT finds evidence of differential treatment of senior women and points out that it may encompass not simply differences in salary but also in space, awards, resources and responses to outside offers, "with women receiving less despite professional accomplishments equal to those of their male colleagues." However, the MIT study was later debunked as "junk science"--its conclusions were erroneous and politically motivated (Kleinfeld, 1999: MIT tarnishes its reputation with gender junk science; Kleinfeld, 2002: Exposing Junk Science. com: The Case of the MIT" Study" on the Status of Women).

Research finds that work by men is often subjectively seen as higher-quality than objectively equal or better work by women compared to how an actual scientific review panel measured scientific competence when deciding on research grants. The results showed that female scientists needed to be at least twice as accomplished as their male counterparts to receive equal credit and that among grant applicants men have statistically significant greater odds of receiving grants than equally qualified women.

Anti-female bias and perceived role incongruency

Research on competence judgments has shown a pervasive tendency to devalue women's work and, in particular, prejudice against women in male-dominated roles which are presumably incongruent for women. Organizational research that investigates biases in perceptions of equivalent male and female competence has confirmed that women who enter high-status, male-dominated work settings often are evaluated more harshly and met with more hostility than equally qualified men. The "think manager - think male" phenomenon reflects gender stereotypes and status beliefs that associate greater status worthiness and competence with men than women. Gender status beliefs shape men's and women's assertiveness, the attention and evaluation their performances receive, and the ability attributed to them on the basis of performance. They also "evoke a gender-differentiated double standard for attributing performance to ability, which differentially biases the way men and women assess their own competence at tasks that are career relevant, controlling for actual ability."Alice H. Eagly and Steven J. Karau (2002) argue that "perceived incongruity between the female gender role and leadership roles leads to two forms of prejudice: (a) perceiving women less favorably than men as potential occupants of leadership roles and (b) evaluating behavior that fulfills the prescriptions of a leader role less favorably when it is enacted by a woman. One consequence is that attitudes are less positive toward female than male leaders and potential leaders. Other consequences are that it is more difficult for women to become leaders and to achieve success in leadership roles." Moreover, research suggests that when women are acknowledged to have been successful, they are less liked and more personally derogated than equivalently successful men. Assertive women who display masculine, agentic traits are viewed as violating prescriptions of feminine niceness and are penalized for violating the status order.

Motherhood penalty and men's marriage premium

Several studies found a significant motherhood penalty on wages and evaluations of workplace performance and competence even after statistically controlling for education, work experience, race, whether an individual works full- or part-time, and a broad range of other human capital and occupational variables. The OECD confirmed the existing literature, in which "a significant impact of children on women’s pay is generally found in the United Kingdom and the United States." However, one study found a wage premium for women with very young children.Stanford University

Stanford University

The Leland Stanford Junior University, commonly referred to as Stanford University or Stanford, is a private research university on an campus located near Palo Alto, California. It is situated in the northwestern Santa Clara Valley on the San Francisco Peninsula, approximately northwest of San...

professor Shelley Correll and colleagues (2007) sent out more than 1,200 fictitious résumés to employers in a large Northeastern city, and found that female applicants with children were significantly less likely to get hired and if hired would be paid a lower salary than male applicants with children. This despite the fact that the qualification, workplace performances and other relevant characteristics of the fictitious job applicants were held constant and only their parental status varied. Mothers were penalized on a host of measures, including perceived competence and recommended starting salary. Men were not penalized for, and sometimes benefited from, being a parent. In a subsequent audit study, Correll et al. found that actual employers discriminate against mothers when making evaluations that affect hiring, promotion, and salary decisions, but not against fathers. The researchers review results from other studies and argue that the motherhood role exists in tension with the cultural understandings of the "ideal worker" role and this leads evaluators to expect mothers to be less competent and less committed to their job. Fathers do not experience these types of workplace disadvantages as understandings of what it means to be a good father are not seen as incompatible with understandings of what it means to be a good worker.

Similarly, Fuegen et al. found that when evaluators rated fictitious applicants for an attorney position, female applicants with children were held to a higher standard than female applicants without children. Fathers were actually held to a significantly lower standard than male non-parents. Cuddy, Fiske, and Glick show that describing a consultant as a mother leads evaluators to rate her as less competent than when she is described as not having children.

Research has also shown there to be a "marriage premium" for men with labor economists frequently reporting that married men earn higher wages than unmarried men, and speculating that this may be attributable to one or more of the following causes: (1) more productive men marry at greater rates (attributing the marriage premium to selection bias), (2) men become more productive following marriage (due to labor market specialization by men and domestic specialization by women), or (3) employers favor married men. Lincoln (2008) found no support for the specialization hypothesis among full-time employed workers. Some studies have suggested this premium is greater for men with children while others have shown fatherhood to have no effect on wages one way or the other.

Gender differences in perceived pay entitlement

According to Serge Desmarais and James Curtis, the "gender gap in pay [...] is related to gender differences in perceptions of pay entitlement." Similarly, Major et al. argue that gender differences in pay expectations play a role in perpetuating non-performance related pay differences between women and men.Perceptions of wage entitlement differ between women and men such that men are more likely to feel worthy of higher pay. while women's sense of wage entitlement is depressed. Women's beliefs about their relatively lower worth and their depressed wage entitlement reflects their lower social status such that when women's status is raised, their wage entitlement raises as well. However, gender-related status manipulation has no impact on men's elevated wage entitlement. Even when men's status is lowered on a specific task (e.g., by telling them that women typically outperform men on this task), men do not reduce their self-pay and respond with elevated projections of their own competence. The usual pattern whereby men assign themselves more pay than women for comparable work might explain why men tend to initiate negotiations more than women.

In a study by psychologist Melissa Williams et al., published in 2010, study participants were given pairs of male and female first names, and asked to estimate their salaries. Men and to a lesser degree women estimated significantly higher salaries for men than women, replicating previous findings. In a subsequent study, participants were placed in the role of employer and were asked to judge what newly hired men and women deserve to earn. The researchers found that men and to a lesser extent women assign higher salaries to men than women based on automatic stereotypic associations. The researchers argue that observations of men as higher earners than women has led to a stereotype that associates men (more than women) with wealth, and that this stereotype itself may serve to perpetuate the wage gap at both conscious and nonconscious levels. For example, a male-wealth stereotype may influence an employer’s initial salary offer to a male job candidate, or a female college graduate’s intuitive sense about what salary she can appropriately ask for at her first job.

Negotiating salaries

A study of the job negotiations of graduating professional school students found that male students were eight times more likely to negotiate starting salaries and pay than female students. In surveys, more than twice as many women than men said they felt "a great deal of apprehension" about negotiating.Harvard University

Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League university located in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States, established in 1636 by the Massachusetts legislature. Harvard is the oldest institution of higher learning in the United States and the first corporation chartered in the country...

professor Hannah Riley and Linda Babcock conducted a study, published in 2007, that found that women are penalized when they try to negotiate starting salaries. Male evaluators tended to rule against women who negotiated but were less likely to penalize men; female evaluators tended to penalize both men and women who negotiated, and preferred applicants who did not ask for more. The study also showed that women who applied for jobs were not as likely to be hired by male managers if they tried to ask for more money, while men who asked for a higher salary were not negatively affected.

Barry Gerhart and Sara Rymes (1991) investigated the salary negotiating behaviors and starting salary outcomes of graduating MBA students and found that women did not negotiate less than men. However, women did obtain lower monetary returns from negotiation. Over the course of a career, the accumulation of such differences may be substantial, according to the researchers.

Danger wage premium

Warren Farrell has argued that a significant cause of the gender earnings gap is men's greater willingness to take on physically dangerous jobs (New York Times 2008).The Bureau of Labor Statistics

Bureau of Labor Statistics

The Bureau of Labor Statistics is a unit of the United States Department of Labor. It is the principal fact-finding agency for the U.S. government in the broad field of labor economics and statistics. The BLS is a governmental statistical agency that collects, processes, analyzes, and...

investigated job traits that are associated with wage premiums, and stated: "The duties most highly valued by the marketplace are generally cognitive or supervisory in nature. Job attributes relating to interpersonal relationships do not seem to affect wages, nor do the attributes of physically demanding or dangerous jobs." Economists Peter Dorman and Paul Hagstrom (1998) state that "The theoretical case for wage compensation for risk is plausible but hardly certain. If workers have utility functions in which the expected likelihood and cost of occupational hazards enter as arguments, if they are fully informed of risks, if firms possess sufficient information on worker expectations and preferences (directly or through revealed preferences), if safety is costly to provide and not a public good, and if risk is fully transacted in anonymous, perfectly competitive labor markets, then workers will receive wage premia that exactly offset the disutility of assuming greater risk of injury or death. Of course, none of these assumptions applies in full and if one or more of them is sufficiently at variance with the real world, actual compensation may be less than utility-offsetting, nonexistent, or even negative - a combination of low pay and poor working conditions."

Impact on pensions

According to a report by the United States Congress Joint Economic CommitteeUnited States Congress Joint Economic Committee

The Joint Economic Committee is one of four standing joint committees of the U.S. Congress. The committee was established as a part of the Employment Act of 1946, which deemed the committee responsible for reporting the current economic condition of the United States and for making suggestions...

, the gender pay gap jeopardizes women's retirement security. Of the multiple sources of income Americans rely on later in life, many are directly linked to a worker’s earnings over his or her career. These include Social Security

Social Security (United States)

In the United States, Social Security refers to the federal Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance program.The original Social Security Act and the current version of the Act, as amended encompass several social welfare and social insurance programs...

benefits, based on lifetime earnings, and defined benefit pension

Pension

In general, a pension is an arrangement to provide people with an income when they are no longer earning a regular income from employment. Pensions should not be confused with severance pay; the former is paid in regular installments, while the latter is paid in one lump sum.The terms retirement...

distributions that are typically calculated using a formula based on a worker’s tenure and salary during peak‐earnings years. The persistent gender pay gap leaves women with less income from these sources than men. For example, older women’s Social Security benefits are 71 % of older men’s benefits ($11,057 for women versus $15,557 for men in 2009). Incomes from public and private pensions based on women’s own work were just 60 % and 48 % of men’s pension incomes, respectively.

See also

- DiscriminationDiscriminationDiscrimination is the prejudicial treatment of an individual based on their membership in a certain group or category. It involves the actual behaviors towards groups such as excluding or restricting members of one group from opportunities that are available to another group. The term began to be...

- Equal Pay Act of 1963Equal Pay Act of 1963The Equal Pay Act of 1963 is a United States federal law amending the Fair Labor Standards Act, aimed at abolishing wage disparity based on sex . It was signed into law on June 10, 1963 by John F. Kennedy as part of his New Frontier Program...

- Equal pay for womenEqual pay for womenEqual pay for women is an issue regarding pay inequality between men and women. It is often introduced into domestic politics in many first world countries as an economic problem that needs governmental intervention via regulation...

- Glass ceilingGlass ceilingIn economics, the term glass ceiling refers to "the unseen, yet unbreachable barrier that keeps minorities and women from rising to the upper rungs of the corporate ladder, regardless of their qualifications or achievements." Initially, the metaphor applied to barriers in the careers of women but...

- Income disparityIncome disparityThe gender pay gap is the difference between male and female earnings expressed as a percentage of male earnings, according to the OECD. The European Commission defines it as the average difference between men’s and women’s hourly earnings...

- Income inequality in the United StatesIncome inequality in the United StatesIncome inequality in the United States of America refers to the extent to which income is distributed in an uneven manner in the US. Data from the United States Department of Commerce, CBO, and Internal Revenue Service indicate that income inequality among households has been increasing...

- Income inequality metricsIncome inequality metricsThe concept of inequality is distinct from that of poverty and fairness. Income inequality metrics or income distribution metrics are used by social scientists to measure the distribution of income, and economic inequality among the participants in a particular economy, such as that of a specific...

- Living wageLiving wageIn public policy, a living wage is the minimum hourly income necessary for a worker to meet basic needs . These needs include shelter and other incidentals such as clothing and nutrition...