Kazohinia

Encyclopedia

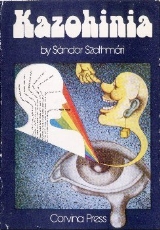

Kazohinia is a novel written in Hungarian

and in Esperanto

by Sándor Szathmári

(1897 – 1974). It appeared first in Hungarian (1941) and was published in Esperanto by SAT (Sennacieca Asocio Tutmonda

) in 1958, and was republished in that language without change in 1998. Several Hungarian editions appeared over the decades (1946, 1957, 1972, 1980, 2009), and an English translation in 1975 (Corvina Press, Budapest). A re-edited edition of this translation is forthcoming in 2012 (New Europe Books), entitled Voyage to Kazohinia--in keeping with the more descriptive titles of the novel's early Hungarian editions, including Gulliver utazása Kazohiniában (Gulliver's Travels in Kazohinia; 1941) and Utazás Kazohiniában (Travels in Kazohinia; 1946), and with the title of the Esperanto edition: Vojaĝo al Kazohinio.

Kazohinia is a utopia

/dystopia

modelled partly on Gulliver's Travels

by the Irishman Jonathan Swift

, and therefore pertains to both utopian and travel genres.

by the British writer Aldous Huxley

. As in that work, there coexist two dissimilar societies - of course separately -, one developed and the other backward.

The Hins are a people who have solved all economic problems: Production and usage of goods is based on need instead of money, and the standard of living is impeccable. The Hins live without any kind of government or administrative body, as their belief is that such would only hinder production. They lead their lives according to the "pure reality of existence," which they call kazo. They experience no emotions, love, beauty or spiritual life.

There are two different main interpretations of the author's intentions:

The protagonist, bored with the inhuman life of the Hins, chooses to live among the insane Behins, who reportedly conform better to his outlook on life. He hopes that in the Behins, living in a walled-off area, he will meet humans with human feelings, similar to himself.

The Behins, however have a totally insane society, where living conditions are supported by the ruling Hins while they themselves are preoccupied with what to the protagonist seem to be senseless ceremonies and all too frequent violent brawls. The Behins deliberately arrange their lives in such a way as to turn reality and logic on their heads, while among the Hins everything is arranged according to reality. While living among them, the protagonist suffers hunger, extreme misery, and even danger of death. This part of the novel is in fact satire, with each insanity of the Behins translating to facets of the Western, Christian society of the protagonist such as war, religion, etiquette, art, and philosophy.

To further emphasize the satire, the protagonist doesn't see the obvious parallels between his homeland and the Behin world, but the writer outlines it by giving the same sentences into the mouths of a Behin leader and a British admiral, replacing only the Behin words on ideals and religion with their English counterparts. The Behins are indeed "real" humans, but as their symbols and customs differ from his own, the protagonist sees them as mere savage madmen.

Language-wise, the novel is surprisingly accessible even at those points when the reader is swamped in an abundance of neologisms with which the Hins and the Behins refer to their strange notions and concepts of life.

. The less probable counter theory goes that after writing some of the book in Hungarian, Szathmári rewrote it and, with Kalocsay's help, finished it first in Esperanto. According to this view, when the Esperanto journal Literatura Mondo, which had accepted it, went out of business at the start of the Second World War, he rewrote it or translated it into Hungarian, resulting in its publication in that language in 1941. In any case, it seems all but certain that the author's Esperanto version was essentially complete or at least well underway before the book's first publication in Hungarian, even if the Esperanto edition did not appear formally until 1958.

called it "insidious"; William Auld

put Szathmári's work on the same level with Swift, John Wells

, and Anatole France

; Michel Duc Goninaz finds that reading Szathmári is a "powerful stimulus to thought"; and Vilmos Benczik pins down Szathmári's work with the expression "sobering humanism."

The American novelist Gregory Maguire

, author of the novels Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West

and Out of Oz, has commented on the novel as follows for the new English edition (New Europe Books, 2012):

"'Tell all the Truth," said Emily Dickinson, 'but tell it Slant.' On such good advice do satirists and speculative sorts venture forward into worlds as varied as Oz, Lilliput, 1984s Oceania, and--now--Kazohinia. In an old world voice with postmodern tones, Sandor Szathmári's Voyage to Kazohinia takes a comic knife to our various conceptions of government, skewering our efforts to determine the most expedient social arrangement for populations to adopt. Gulliver, the belittled individual with an oversize sense of capacity, earns our fulsome affection, if leavened with our apprehension about his own blindness. Crusoe encountering Friday, Alice at a loss at the Mad Tea Party: Make room for the new Gulliver! He has brought home news out of Kazohinia."

was a spiritual father to me” — Dezső Keresztury quotes Szathmári in his afterword to Kazohina.

Aldous Huxley

's Brave New World

has also been mentioned, although the author is quoted by Keresztury in his afterword, “I wrote Kazohinia two years before Brave New World appeared. I could not have imitated it more perfectly if I had tried. Anyway, it was my good fortune that it was conceived two years earlier, because there are so many similarities between the two that I would never have been so bold as to write Kazohinia had I read Brave New World first.” Although one prominent literary scholar in Hungary believes that Szathmári had probably heard or read about Brave New World prior to writing Kazohinia, there is no evidence to suggest that in fact he had read the novel, whose Hungarian translation was published only after the author wrote Kazohinia. Also, despite some overlapping themes and a mutual interest in describing the technology of a possible future, Kazohinia — set in the present rather than the future, and highly comic throughout — is a fundamentally different book.

Hungarian language

Hungarian is a Uralic language, part of the Ugric group. With some 14 million speakers, it is one of the most widely spoken non-Indo-European languages in Europe....

and in Esperanto

Esperanto

is the most widely spoken constructed international auxiliary language. Its name derives from Doktoro Esperanto , the pseudonym under which L. L. Zamenhof published the first book detailing Esperanto, the Unua Libro, in 1887...

by Sándor Szathmári

Sándor Szathmári

Szathmári Sándor was a Hungarian writer, mechanical engineer, Esperantist, one of the leading figures in Esperanto literature.-Family background:Szathmári was born in Gyula...

(1897 – 1974). It appeared first in Hungarian (1941) and was published in Esperanto by SAT (Sennacieca Asocio Tutmonda

Sennacieca Asocio Tutmonda

Sennacieca Asocio Tutmonda is an independent worldwide cultural Esperanto association of a general left-wing orientation. Its headquarters are in Paris. According to Jacques Schram, chairman of the Executive Committee, the membership totalled 881 in 2003...

) in 1958, and was republished in that language without change in 1998. Several Hungarian editions appeared over the decades (1946, 1957, 1972, 1980, 2009), and an English translation in 1975 (Corvina Press, Budapest). A re-edited edition of this translation is forthcoming in 2012 (New Europe Books), entitled Voyage to Kazohinia--in keeping with the more descriptive titles of the novel's early Hungarian editions, including Gulliver utazása Kazohiniában (Gulliver's Travels in Kazohinia; 1941) and Utazás Kazohiniában (Travels in Kazohinia; 1946), and with the title of the Esperanto edition: Vojaĝo al Kazohinio.

Kazohinia is a utopia

Utopia

Utopia is an ideal community or society possessing a perfect socio-politico-legal system. The word was imported from Greek by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book Utopia, describing a fictional island in the Atlantic Ocean. The term has been used to describe both intentional communities that attempt...

/dystopia

Dystopia

A dystopia is the idea of a society in a repressive and controlled state, often under the guise of being utopian, as characterized in books like Brave New World and Nineteen Eighty-Four...

modelled partly on Gulliver's Travels

Gulliver's Travels

Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World, in Four Parts. By Lemuel Gulliver, First a Surgeon, and then a Captain of Several Ships, better known simply as Gulliver's Travels , is a novel by Anglo-Irish writer and clergyman Jonathan Swift that is both a satire on human nature and a parody of...

by the Irishman Jonathan Swift

Jonathan Swift

Jonathan Swift was an Irish satirist, essayist, political pamphleteer , poet and cleric who became Dean of St...

, and therefore pertains to both utopian and travel genres.

Plot introduction

As in the Gulliverian prototype, the premise is a shipwreck with a solitary survivor, who finds himself in an unknown land, namely that of the Hins, which contains a minority group, namely the Behins. Accordingly, this work by a Hungarian writer relates not so much to Swift's work, but more precisely to Brave New WorldBrave New World

Brave New World is Aldous Huxley's fifth novel, written in 1931 and published in 1932. Set in London of AD 2540 , the novel anticipates developments in reproductive technology and sleep-learning that combine to change society. The future society is an embodiment of the ideals that form the basis of...

by the British writer Aldous Huxley

Aldous Huxley

Aldous Leonard Huxley was an English writer and one of the most prominent members of the famous Huxley family. Best known for his novels including Brave New World and a wide-ranging output of essays, Huxley also edited the magazine Oxford Poetry, and published short stories, poetry, travel...

. As in that work, there coexist two dissimilar societies - of course separately -, one developed and the other backward.

The Hins are a people who have solved all economic problems: Production and usage of goods is based on need instead of money, and the standard of living is impeccable. The Hins live without any kind of government or administrative body, as their belief is that such would only hinder production. They lead their lives according to the "pure reality of existence," which they call kazo. They experience no emotions, love, beauty or spiritual life.

There are two different main interpretations of the author's intentions:

- Although the theme can be seen as a criticism of developed society, where highly progressive invention goes hand in hand with the loss of human feelings, Dezső KereszturyDezső KereszturyDezső Keresztury was a Hungarian poet and politician, who served as Minister of Religion and Education between 1945 and 1947. He became member of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences in 1982.-References:*...

, the writer of the epilogue of the Hungarian edition stated that this is not what Szathmáry intended - he created the Hins as the ideal society that occupies itself with the "real" stuff of life instead of "unreal" phantasmagories such as nations, religion, and money, that, regardless of intentions, cause people considerable misery.

- Another interpretation is that the author satires both human society and communist utopias – which, in his assessment, lead equally to such disastrous consequences as massacres.

The protagonist, bored with the inhuman life of the Hins, chooses to live among the insane Behins, who reportedly conform better to his outlook on life. He hopes that in the Behins, living in a walled-off area, he will meet humans with human feelings, similar to himself.

The Behins, however have a totally insane society, where living conditions are supported by the ruling Hins while they themselves are preoccupied with what to the protagonist seem to be senseless ceremonies and all too frequent violent brawls. The Behins deliberately arrange their lives in such a way as to turn reality and logic on their heads, while among the Hins everything is arranged according to reality. While living among them, the protagonist suffers hunger, extreme misery, and even danger of death. This part of the novel is in fact satire, with each insanity of the Behins translating to facets of the Western, Christian society of the protagonist such as war, religion, etiquette, art, and philosophy.

To further emphasize the satire, the protagonist doesn't see the obvious parallels between his homeland and the Behin world, but the writer outlines it by giving the same sentences into the mouths of a Behin leader and a British admiral, replacing only the Behin words on ideals and religion with their English counterparts. The Behins are indeed "real" humans, but as their symbols and customs differ from his own, the protagonist sees them as mere savage madmen.

Literary technique

Humor contrasts with the serious content in a masterful way, ensuring an easy read. While the first half of the book, describing the Hins, is a utopia of sorts despite the question surrounding the author's intentions, and uses humor to lighten the mood, the second half, about Behin society, wields humor as a merciless weapon, debunking and ridiculing every aspect of our irrational world.Language-wise, the novel is surprisingly accessible even at those points when the reader is swamped in an abundance of neologisms with which the Hins and the Behins refer to their strange notions and concepts of life.

Publication

There has been some dispute as to whether Szathmári wrote the novel first in Hungarian or in Esperanto, and this issue is unlikely to ever be fully resolved. But most leading scholars in Hungary today believe he first wrote it in his native tongue, Hungarian, and that once he became sufficiently fluent in Esperanto, he then translated the book into that language as well, with some assistance from Kálmán KalocsayKálmán Kalocsay

Kálmán Kalocsay , in Hungarian name order Kalocsay Kálmán is one of the foremost figures in the history of Esperanto literature...

. The less probable counter theory goes that after writing some of the book in Hungarian, Szathmári rewrote it and, with Kalocsay's help, finished it first in Esperanto. According to this view, when the Esperanto journal Literatura Mondo, which had accepted it, went out of business at the start of the Second World War, he rewrote it or translated it into Hungarian, resulting in its publication in that language in 1941. In any case, it seems all but certain that the author's Esperanto version was essentially complete or at least well underway before the book's first publication in Hungarian, even if the Esperanto edition did not appear formally until 1958.

Comments about the book

Beyond being an often overlooked classic of Hungarian literature that enjoys a cult-like status in its native land, Kazohinia is considered one of the main original novels in Esperanto, in which its title is Vojaĝo al Kazohinio. Kálmán KalocsayKálmán Kalocsay

Kálmán Kalocsay , in Hungarian name order Kalocsay Kálmán is one of the foremost figures in the history of Esperanto literature...

called it "insidious"; William Auld

William Auld

William Auld was a Scottish poet, author, translator and magazine editor who wrote chiefly in Esperanto. He was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1999, 2004, and 2006 making him the first and only person to be nominated for works in Esperanto...

put Szathmári's work on the same level with Swift, John Wells

John Wells

John Wells may refer to:People* John C. Wells , British linguist, phonetician and Esperantist* Jonathan Wells , real name John Corrigan Wells...

, and Anatole France

Anatole France

Anatole France , born François-Anatole Thibault, , was a French poet, journalist, and novelist. He was born in Paris, and died in Saint-Cyr-sur-Loire. He was a successful novelist, with several best-sellers. Ironic and skeptical, he was considered in his day the ideal French man of letters...

; Michel Duc Goninaz finds that reading Szathmári is a "powerful stimulus to thought"; and Vilmos Benczik pins down Szathmári's work with the expression "sobering humanism."

The American novelist Gregory Maguire

Gregory Maguire

Gregory Maguire is an American writer. He is the author of the novels Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West, Confessions of an Ugly Stepsister, and many other novels for adults and children...

, author of the novels Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West

Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West

Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West, is a parallel novel published in 1995 written by Gregory Maguire and illustrated by Douglas Smith. It is a revisionist look at the land and characters of Oz from L. Frank Baum's 1900 novel The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, its sequels, and the...

and Out of Oz, has commented on the novel as follows for the new English edition (New Europe Books, 2012):

"'Tell all the Truth," said Emily Dickinson, 'but tell it Slant.' On such good advice do satirists and speculative sorts venture forward into worlds as varied as Oz, Lilliput, 1984s Oceania, and--now--Kazohinia. In an old world voice with postmodern tones, Sandor Szathmári's Voyage to Kazohinia takes a comic knife to our various conceptions of government, skewering our efforts to determine the most expedient social arrangement for populations to adopt. Gulliver, the belittled individual with an oversize sense of capacity, earns our fulsome affection, if leavened with our apprehension about his own blindness. Crusoe encountering Friday, Alice at a loss at the Mad Tea Party: Make room for the new Gulliver! He has brought home news out of Kazohinia."

Source

This entry began as a translation of the Vikipedio article in Esperanto. Additional information was added from the entry on its author, and further insight came from the afterword written by Dezső Keresztúry to the English translation published in Hungary in 1975, as well as discussions and correspondence in 2011 with three noted literary scholars in Hungary.Precursors

“KarinthyFrigyes Karinthy

Frigyes Karinthy was a Hungarian author, playwright, poet, journalist, and translator. He was the first proponent of the six degrees of separation concept, in his 1929 short story, Chains . Karinthy remains one of the most popular Hungarian writers...

was a spiritual father to me” — Dezső Keresztury quotes Szathmári in his afterword to Kazohina.

Aldous Huxley

Aldous Huxley

Aldous Leonard Huxley was an English writer and one of the most prominent members of the famous Huxley family. Best known for his novels including Brave New World and a wide-ranging output of essays, Huxley also edited the magazine Oxford Poetry, and published short stories, poetry, travel...

's Brave New World

Brave New World

Brave New World is Aldous Huxley's fifth novel, written in 1931 and published in 1932. Set in London of AD 2540 , the novel anticipates developments in reproductive technology and sleep-learning that combine to change society. The future society is an embodiment of the ideals that form the basis of...

has also been mentioned, although the author is quoted by Keresztury in his afterword, “I wrote Kazohinia two years before Brave New World appeared. I could not have imitated it more perfectly if I had tried. Anyway, it was my good fortune that it was conceived two years earlier, because there are so many similarities between the two that I would never have been so bold as to write Kazohinia had I read Brave New World first.” Although one prominent literary scholar in Hungary believes that Szathmári had probably heard or read about Brave New World prior to writing Kazohinia, there is no evidence to suggest that in fact he had read the novel, whose Hungarian translation was published only after the author wrote Kazohinia. Also, despite some overlapping themes and a mutual interest in describing the technology of a possible future, Kazohinia — set in the present rather than the future, and highly comic throughout — is a fundamentally different book.