.gif)

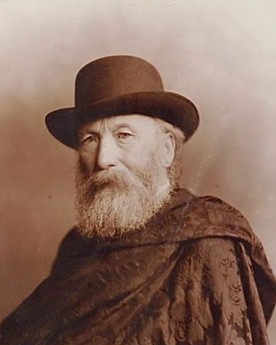

James Stephens (Irish nationalist)

Encyclopedia

Irish Republican Brotherhood

The Irish Republican Brotherhood was a secret oath-bound fraternal organisation dedicated to the establishment of an "independent democratic republic" in Ireland during the second half of the 19th century and the start of the 20th century...

(I.R.B), also referred to as the Irish Revolutionary Brotherhood by contemporaries.

Early life

References to his early life, according to one of his biographers, Desmond Ryan, are obscure and limited to Stephens' own vague autobiographical recollections. James Stephens was born and spent his childhood at Lilac Cottage, Blackmill Street, KilkennyKilkenny

Kilkenny is a city and is the county town of the eponymous County Kilkenny in Ireland. It is situated on both banks of the River Nore in the province of Leinster, in the south-east of Ireland...

, on 26 January 1825. No birth records have ever been located, but a baptismal record from St. Mary’s Parish is dated 29 July 1825. According to Marta Ramón, there is reason to believe that he was born out of wedlock in late July 1825; however, according to Stephens his exact date of birth was 26 January.

.jpg)

For many years, his father had been a clerk to auctioneer and bookseller William Jackson Douglas whose offices and warehouses were on High Street, Kilkenny. Ryan has the order of the name as William Douglas Jackson, of Rose Inn Street, in his Stephens' biography Fenian Chief. John Stephens, as well as his earnings as a clerk, also had some small property in Kilkenny; records show him as occupier of 13 Evan’s Lane, St. Mary’s Parish and 22 Chapel Lane, St. Canice’s Parish, his residence at the time of the rising.

Little is known of Stephens’s mother and according to Ryan, it is possible he had no memory of her. Only briefly does Stephens mention her in his writings, although her name appears on Stephens' marriage certificate in 1863. His mother’s people, the Caseys, were shopkeepers; one account says they ran a small hardware business. In April 1846 James and his sister, Anne, became sponsors to their cousin, Joseph Casey, at his baptism in St. Mary’s Cathedral, Kilkenny. Joseph Casey would later be acquitted of charges of suspected Fenian activities in England in 1867. During Stephens' second exile in Paris, he would spend much time with the Caseys, who emigrated to France after the trial of Joseph. Stephens would be expelled from France on 12 March 1885 because of a series of press interviews given by Patrick Casey advocating the "dynamite war," which Stephens had repudiated consistently.

.jpg)

An omnivorous reader, Stephens, according to Ryan, was a silent and aloof student with a thirst for knowledge, a characteristic throughout his life. Aged 20, Stephens was apprenticed to a civil engineer and obtained a post in a Kilkenny office for work then in progress on the Limerick and Waterford Railway

Great Southern and Western Railway

The Great Southern and Western Railway was the largest Irish gauge railway company in Ireland in the late 19th and early 20th centuries...

in 1844.

Stephens was in a romantic relationship with a young lady, Miss Hilton, at this time, although she did not share his nationalist sentiments. This relationship ended shortly after the rising.

According to Ryan, for an unexplained reason, Stephens had already become a “revolutionary in spirit” by his mid twenties. The one influence he mentions in this period was that of Dr. Robert Cane a former Mayor of Kilkenny, a cultural propagandist, and a moderate Young Ireland

Young Ireland

Young Ireland was a political, cultural and social movement of the mid-19th century. It led changes in Irish nationalism, including an abortive rebellion known as the Young Irelander Rebellion of 1848. Many of the latter's leaders were tried for sedition and sentenced to penal transportation to...

er.

As a young man, Stephens had declined to affiliate with any political organisation. He distrusted the conciliatory Repealers of the O’Connell school, describing the Repeal agitator as “a wind-bag”; the Young Ireland

Young Ireland

Young Ireland was a political, cultural and social movement of the mid-19th century. It led changes in Irish nationalism, including an abortive rebellion known as the Young Irelander Rebellion of 1848. Many of the latter's leaders were tried for sedition and sentenced to penal transportation to...

Confederation, however, was of “sterner stuff,” and he was better inclined towards them. His father also was a strong sympathiser and was moderately active in local politics. The Kilkenny Irish Confederation club would later lend some economic assistance to Stephens during his Paris exile.

Ireland in the 1840s was devastated by the Great Famine; the Repeal movement was in decline, and the country moved towards insurrection, aided by the incitements of John Mitchel

John Mitchel

John Mitchel was an Irish nationalist activist, solicitor and political journalist. Born in Camnish, near Dungiven, County Londonderry, Ireland he became a leading member of both Young Ireland and the Irish Confederation...

and James Fintan Lalor

James Fintan Lalor

James Fintan Lalor was an Irish revolutionary, journalist, and “one of the most powerful writers of his day.” A leading member of the Irish Confederation , he was to play an active part in both the Rebellion in July 1848 and the attempted Rising in September of that same year...

. Stephens sympathies lay more with the Mitchel and Lalor brand of republicanism, than with Charles Gavan Duffy

Charles Gavan Duffy

Additional Reading*, Allen & Unwin, 1973.*John Mitchel, A Cause Too Many, Aidan Hegarty, Camlane Press.*Thomas Davis, The Thinker and Teacher, Arthur Griffith, M.H. Gill & Son 1922....

’s and William Smith O'Brien

William Smith O'Brien

William Smith O'Brien was an Irish Nationalist and Member of Parliament and leader of the Young Ireland movement. He was convicted of sedition for his part in the Young Irelander Rebellion of 1848, but his sentence of death was commuted to deportation to Van Diemen's Land. In 1854, he was...

’s mild constitutionalism. This would come to a head with the revolutions sweeping Europe from the Paris barricades of February 1848. According to Ryan, Stephens was caught up in these impulses and added secret drilling to his work of railway construction.

Young Ireland and 1848

The only written accounts of Stephens political opinions prior to 1848 are the letters he wrote just after the insurrection and his recollections published in the Irishman newspaper beginning on the 4 February 1882, and his “Notes on a 3,000 miles walk through Ireland” published in the Weekly Freeman from the 6 October 1883.

Van Diemen's Land

Van Diemen's Land was the original name used by most Europeans for the island of Tasmania, now part of Australia. The Dutch explorer Abel Tasman was the first European to land on the shores of Tasmania...

(modern-day Tasmania

Tasmania

Tasmania is an Australian island and state. It is south of the continent, separated by Bass Strait. The state includes the island of Tasmania—the 26th largest island in the world—and the surrounding islands. The state has a population of 507,626 , of whom almost half reside in the greater Hobart...

, Australia

Australia

Australia , officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country in the Southern Hemisphere comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It is the world's sixth-largest country by total area...

) by a packed jury under the purposely enacted Treason Felony Act

Treason Felony Act 1848

The Treason Felony Act 1848 is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. The Act is still in force. It is a law which protects HM the Queen and the Crown....

, leadership of the Confederation fell to William Smith O'Brien. O'Brien arrived in Kilkenny on 24 July 1848 to call on the people to confront "the perils and the honours of a righteous war." The next day, at a meeting of the Confederate clubs, Stephens was called upon to appear on the platform by his friends were he then delivered his maiden speech;

Later Stephens and his father went to a private meeting in the Victoria Hotel, when a Mr. John Grace rushed in to say there was someone with a warrant for the arrest of O'Brien at the Rose Inn. A Mr. Kavanagh who was present at the meeting asked who would come with him to take the detective prisoner, which Stephens agreed to do. This would be the last time Stephens would ever see his father again. Having gone to get some arms, the two men went to the Inn and detained the individual. It later turned out to be Patrick O'Donoghue

Patrick O'Donoghue (Young Irelander)

Patrick O'Donoghue , also known as Patrick O'Donohoe, from Clonegal, County Carlow, was an Irish Nationalist revolutionary and journalist, a member of the Young Ireland movement.-Young Irelander Rebellion:...

a member of the Confederate council with a message for O’Brien. Until his identity could be established, it was decided he would be brought to O'Brien with the clear warning that if he was who he said he was he would forgive their zeal, if however he tried to escape he would be shot.

.jpg)

Thurles

Thurles is a town situated in North Tipperary, Ireland. It is a civil parish in the historical barony of Eliogarty and is also an ecclesiastical parish in the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Cashel and Emly...

to meet up with O’Brien they came across P.J. Smith

Patrick James Smyth

Patrick James Smyth "Nicaragua Smyth" was an Irish politician and journalist.He was educated at Clongowes Wood College where he became friends with Thomas Francis Meagher, with whom he joined the Repeal Association in 1844...

a leading member of the Young Irelanders who vouched for O’Donoghue. Smith would later successfully plan the escape of Mitchel from Van Diemen's Land

Van Diemen's Land

Van Diemen's Land was the original name used by most Europeans for the island of Tasmania, now part of Australia. The Dutch explorer Abel Tasman was the first European to land on the shores of Tasmania...

, was on his way to Dublin to arrange plans to tear up the railway line in Thurles and the Dublin suburbs and for the Meath

County Meath

County Meath is a county in Ireland. It is part of the Mid-East Region and is also located in the province of Leinster. It is named after the ancient Kingdom of Mide . Meath County Council is the local authority for the county...

clubs to create a diversion. Stephens and O’Donoghue agreed to take charge of the Thurles line, later passing the order on to the local Confederates, who destroyed parts of the Great Southern and Western Railway

Great Southern and Western Railway

The Great Southern and Western Railway was the largest Irish gauge railway company in Ireland in the late 19th and early 20th centuries...

line near the town.

Stephens, O’Donoghue and Kavanagh headed to Cashel

Cashel, County Tipperary

Cashel is a town in South Tipperary in Ireland. Its population was 2936 at the 2006 census. The town gives its name to the ecclesiastical province of Cashel. Additionally, the cathedra of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Cashel and Emly was originally in the town prior to the English Reformation....

and arrived there between ten and eleven o’clock on the 26 July and proceeded to the home of Michael Doheny

Michael Doheny

Michael Doheny was an Irish writer and member of the Young Ireland movement.-Early life:The third son of Michael Doheny, of Brookhill, he was born at Brookhill, near Fethard, Co. Tipperary, and married a Miss O'Dwyer of that county...

. There they found with some difficulty, O’Brien, John Blake Dillon

John Blake Dillon

John Blake Dillon was an Irish writer and Politician who was one of the founding members of the Young Ireland movement....

and James Cantwell. It was here that Kavanagh decided that insurrection was hopeless and left, and according to Ramón, Stephens “took the most fateful decision of his life and resolved to stay.” Stephens and O'Donoghue said they would follow O'Brien to the end according to Ryan. Stephens was appointed aide de camp to William Smith O'Brien on the spot, later Doheny would write, "when they expected that every man would make a fortress in his heart, they were almost abandoned, but their resolution remained unchanged."

From Cashel they then headed towards Killenaule

Killenaule

Killenaule is a town and a civil parish in the barony of Slievardagh, South Tipperary in Ireland. It is also one half of the ecclesiastical parish of Killenaule and Moyglass in the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Cashel and Emly. It is located east of Cashel on the R689 and R691 regional roads...

before making for Mullinahone

Mullinahone

Mullinahone is a village in the barony of Slievardagh, South Tipperary in Ireland. It is also a parish in the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Cashel and Emly.The Irish Census of 2006 recorded the village as having a population of 372.-Location and access:...

were for the first time Stephens would meet Charles J. Kickham

Charles Kickham

Charles Joseph Kickham was an Irish revolutionary, novelist, poet, journalist and one of the most prominent members of the Irish Republican Brotherhood.-Early life:...

who would become a future leader of the Irish Republican Brotherhood

Irish Republican Brotherhood

The Irish Republican Brotherhood was a secret oath-bound fraternal organisation dedicated to the establishment of an "independent democratic republic" in Ireland during the second half of the 19th century and the start of the 20th century...

. It was in Mullinahone that they had their first confrontation with the authorities, a somewhat “tragicomic” affair displaying both “moral integrity and revolutionary naivety.” On Thursday the 27 July they moved towards Ballingarry

Ballingarry

Ballingarry is a village in the barony of Slievardagh, South Tipperary in Ireland. It is also a parish in the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Cashel and Emly. The village is situated near the Kilkenny border on route R691. Ballingarry is located near Slievenamon.-Amenities:On the Main Street may be...

were they were joined by Terence Bellew MacManus who had come from Liverpool

Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough of Merseyside, England, along the eastern side of the Mersey Estuary. It was founded as a borough in 1207 and was granted city status in 1880...

.

On Friday the 28 while in Killenaule, news reached them that a party of dragoons were on their way to arrest O’Brien, which resulted in two barricades being erected in the main street which Stephens armed with a rifle manned along with thirty men mostly armed with pikes, pitch-forks and a couple of muskets. As the dragoons approached the barricade Stephens levelled his rifle at their commander a Captain Longmore, as Dillon mounted the barricade and asked if they were there to arrest O’Brien. When Captain Longmore answered that they had no warrant for O’Brien, they were lead thorough the barricade and allowed to go through the town.

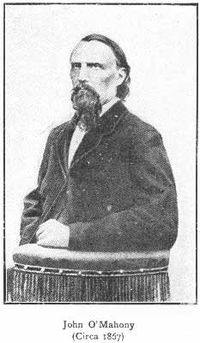

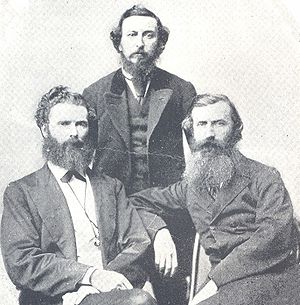

Leaving Killenaule, they carried on towards Ballingarry, conducting drilling exercises at the collieries before moving on to Boulagh Commons two miles outside town. During the night they were joined by a number of the Young Ireland leaders who had been trying to co-ordinate their efforts unsuccessfully. They held a council of war at the local inn, with fourteen members present, including Stephens and joined by both John O'Mahony

John O'Mahony

John O'Mahony may refer to:*John O'Mahony , founder of the Irish Republican Brotherhood *John O'Mahony , Irish Fine Gael politician representing Mayo and twice an All-Ireland winner managing the Galway Football Team*Sean Matgamna , also known as John O'Mahony, Trotskyist theorist*Seán O'Mahony ,...

and Thomas Francis Meagher

Thomas Francis Meagher

-Young Ireland:Meagher returned to Ireland in 1843, with undecided plans for a career in the Austrian army, a tradition among a number of Irish families. In 1844 he traveled to Dublin with the intention of studying for the bar. He became involved in the Repeal Association, which worked for repeal...

. Discussing the situation, the majority of leaders favoured going into hiding until the harvests were in, and making an attempt under more favourable circumstances, however O'Brien refused adamantly. It was decided then that Dillon, Doheny, Meagher and O'Mahony would try to rally the various districts while O'Brien would hold on were he was. While present at the council, Stephens did not offer his opinions, due according to Ramón, citing Stephens' personal recollections, because of his "youthful modesty."

On Saturday morning 29 July in Callan

Callan

-People:Callan is the birth place of some famous people, namely:* Edmund Ignatius Rice, founder of the Irish Christian Brothers and the Presentation Brothers* Callan also has links with Asa Griggs Candler's family and the Coca-Cola company....

Sub-Inspector Thomas Trant received an order from Purefoy Poe, J.P. to proceed to the Commons. As Trant’s force of 46 men passed through Nine-Mile House they were observed by John Kavanagh president of one of the Dublin clubs. Borrowing a horse he rode off to warn O’Brien of their approach. The leaders at this time had just agreed to move on Urlingford

Urlingford

Urlingford is a town in the barony of Galmoy, County Kilkenny, Ireland.The town lies on the R639. The M8 motorway runs just west of the town, from which both Urlingford and nearby Johnstown are accessed via junction four. Urlingford is a bus hub, with major operator JJ Kavanagh and Sons based there...

when Kavanagh arrived. It was decided after a short discussion that they would stay and confront the police. A barricade was quickly thrown up, and Stephens was placed in a house with a number of armed men overlooking this barricade.

On coming closer to the town, Trant observed the barricades and a party of rebels prepared to meet them, with a multitude approaching them from all sides. Moving forward Trant then turned his men right and spotting an isolated house on the top of a hill rushed to the building and took refuge inside. The house belonged to a widow, Margaret McCormack while out of the house at the time, had left her five children there. Taking the children hostage, the police quickly began to barricade the windows and doors.

Reports of his death were published in the Kilkenny Moderator on 19 August with the intention of throwing the authorities off his trail. Stephens fled Ireland and escaped to France were he remained for the next seven years.

Paris exile

Young Irelander Rebellion of 1848

The Young Irelander Rebellion was a failed Irish nationalist uprising led by the Young Ireland movement. It took place on 29 July 1848 in the village of Ballingarry, County Tipperary. After being chased by a force of Young Irelanders and their supporters, an Irish Constabulary unit raided a house...

James Stephens

James Stephens (Irish nationalist)

James Stephens was an Irish Republican and the founding member of an originally unnamed revolutionary organisation in Dublin on 17 March 1858, later to become known as the Irish Republican Brotherhood , also referred to as the Irish Revolutionary Brotherhood by contemporaries.-Early...

and John O'Mahony

John O'Mahony

John O'Mahony may refer to:*John O'Mahony , founder of the Irish Republican Brotherhood *John O'Mahony , Irish Fine Gael politician representing Mayo and twice an All-Ireland winner managing the Galway Football Team*Sean Matgamna , also known as John O'Mahony, Trotskyist theorist*Seán O'Mahony ,...

went to the Continent to avoid arrest. In Paris they supported themselves through teaching and translation work and planned the next stage of "the fight to overthrow British rule in Ireland." Stephens in Paris, set himself three tasks, during his seven years of exile. They were, to keep alive, pursue knowledge, and master the technique of conspiracy. At this time Paris particularly, was interwoven with a network of secret political societies. They became members of one the most powerful of these societies and acquired the secrets of some of the ablest and "most profound masters of revolutionary science" which the nineteenth century had produced, as to the means of inviting and combining people for the purposes of successful revolution.

In 1853 O'Mahony went to America and founded the Emmet Monument Association

Emmet Monument Association

The Emmet Monument Association was a mid-nineteenth century secret military organization with the special purpose of training men to attack England and free Ireland. It was established in the mid 1850s, by John O'Mahony and Michael Doheny refugees from the Young Irelander Rebellion of 1848...

3,000 mile walk

Stephens in early 1856 began making his way back to Ireland, stopping first in London. On arriving in Dublin, Stephens began what he described as his three thousand mile walk through Ireland, meeting some of those who had taken part in the 1848 /49 revolutionary movements, including Philip GrayPhilip Gray

Philip Gray was an Irish republican, revolutionary and a member of the Irish Confederation. He took part in the Risings of 1848 and 1849 along with James Fintan Lalor and both James Stephens and John O'Mahony, who would go on to establish the Irish Republican Brotherhood in Ireland and the Fenian...

, Thomas Clarke Luby

Thomas Clarke Luby

Thomas Clarke Luby was an Irish revolutionary, author, journalist and one of the founding members of the Irish Republican Brotherhood.-Early life:...

and Peter Langan.

Founding of the IRB

Irish Republican Brotherhood

The Irish Republican Brotherhood was a secret oath-bound fraternal organisation dedicated to the establishment of an "independent democratic republic" in Ireland during the second half of the 19th century and the start of the 20th century...

commenced.

The original oath, with its clauses of secrecy was drawn up by Luby under Stephens direction in Stephens room in Donnelly’s which was situated behind Lombard Street. Luby then swore Stephens in and he did likewise. The oath read:

Those present in Langan's, lathe-maker and timber merchant, 16 Lombard Street

Lombard Street

There are several famous Lombard Streets:* Lombard Street , famed for its twists and turns* Lombard Street, London, leading from the Bank of England to Gracechurch Street...

for that first meeting apart from Stephens and Luby were Peter Langan, Charles Kickham

Charles Kickham

Charles Joseph Kickham was an Irish revolutionary, novelist, poet, journalist and one of the most prominent members of the Irish Republican Brotherhood.-Early life:...

, Joseph Denieffe and Garrett O'Shaughnessy. Later it would include members of the Phoenix National and Literary Society, which was formed in 1856 by Jeremiah O'Donovan Rossa

Jeremiah O'Donovan Rossa

Jeremiah O'Donovan Rossa , was an Irish Fenian leader and prominent member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood. His life as an Irish Fenian is well documented but he is perhaps known best in death for the graveside oration given at his funeral by Pádraig Pearse.-Life in Ireland:He was born at...

in Skibbereen

Skibbereen

Skibbereen , is a town in County Cork, Ireland. It is the most southerly town in Ireland. It is located on the N71 national secondary road.The name "Skibbereen" means "little boat harbour." The River Ilen which runs through the town reaches the sea at Baltimore.-History:Prior to 1600 most of the...

.

America

Stephens arrived in New York on Wednesday 13 October 1858. After a trying voyage, he went first to the Metropolitan Hotel to recuperate before going to meet Doheny and O’Mahony.Stephens succeeded in his mission to America, though according to Ryan, Stephens omits this fact from his diary. It is he says only by the definite assertions of John O’Leary do we know of this success, overcoming the many obstacles placed in his way including the Directory and the ’48 leaders. According to Ryan, Stephens would bind in Ireland and America for nearly a decade warring and ineffective elements into a formidable political and revolutionary force.

America diary

While in America Stephens kept a diary, which opens with the date 7 January 1859, three months after his arrival and with the last entry on the 25 March 1860. The original copy of the diary is now kept in the Public Records Office in Northern Ireland.Irish People

Denis Dowling Mulcahy

Denis Dowling Mulcahy was a leading member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood and a medical doctor.He was born in Redmondstown, County Tipperary, Ireland and later lived at Powerstown, near Clonmel....

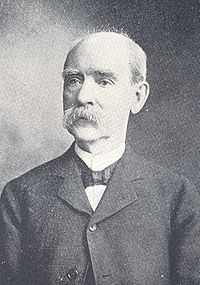

as the editorial staff. O’Donovan Rossa and James O’Connor

James O'Connor (Irish politician)

James O'Connor was an Irish journalist and nationalist politician who sat in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom as a Member of Parliament from 1892 to 1910, first for the anti-Parnellite Irish National Federation and then for the re-united Irish Parliamentary Party .He was born in the...

had charge of the business office, with John Haltigan being the printer. John O'Leary was brought from London to take charge in the role of Editor. Shortly after the establishment of the paper, Stephens departed on an America tour, and to attend to organizational matters. Before leaving, he entrusted to Luby a document containing secret resolutions on the Committee of Organization or Executive of the IRB. Though Luby intimated its existence to O’Leary, he did not inform Kickham as there seemed no necessity. This document would later form the basis of the prosecution against the staff of the Irish People. The document read:

Arrest and suppression

On the 15 July 1865 American-made plans for a rising in Ireland were discovered when the emissary lost them at Kingstown railway station. They found their way to Dublin Castle and to Superintendent Daniel Ryan head of G Division. Ryan had an informer within the offices of the Irish People named Pierce Nagle, he supplied Ryan with an “action this year” message on its way to the IRB unit in Tipperary. With this information, Ryan raided the offices of the Irish People on Thursday 15 September, followed by the arrests of O’Leary, Luby and O’Donovan Rossa. Kickham was caught after a month on the run.Escape

Stephens would also be caught but with the support of Fenian prison warders, John J. Breslin and Daniel Byrne was less than a fortnight in Richmond Bridewell when he vanished and escaped to FranceFrance

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

. The last number of the paper is dated 16 September 1865.

Conclusion

His house in KilkennyKilkenny

Kilkenny is a city and is the county town of the eponymous County Kilkenny in Ireland. It is situated on both banks of the River Nore in the province of Leinster, in the south-east of Ireland...

, situated near the Church of Ireland

Church of Ireland

The Church of Ireland is an autonomous province of the Anglican Communion. The church operates in all parts of Ireland and is the second largest religious body on the island after the Roman Catholic Church...

Cathedral, is marked by a plaque.

Sources

- Seán CroninSeán CroninSeán Cronin was a journalist and former Irish Army officer and twice Irish Republican Army chief of staff.Cronin was born in Dublin in 1920 but spent his childhood years in Ballinskelligs, in the County Kerry Gaeltacht....

, The McGarrity Papers, Anvil Books, Ireland, 1972 - T. F. O'Sullivan, Young Ireland, The Kerryman Ltd. 1945

- Desmond Ryan, The Fenian Chief: A Biography of James Stephens, Hely Thom LTD, Dublin, 1967

- Leon Ó Broin, Fenian Fever: An Anglo-American Delemma, Chatto & Windus, London, 1971, ISBN 0 7011 1749 4.

- John O'Leary, Recollections of Fenians and Fenianism, Downey & Co., Ltd, London, 1896 (Vol. I & II)

- Jeremiah O'Donovan RossaJeremiah O'Donovan RossaJeremiah O'Donovan Rossa , was an Irish Fenian leader and prominent member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood. His life as an Irish Fenian is well documented but he is perhaps known best in death for the graveside oration given at his funeral by Pádraig Pearse.-Life in Ireland:He was born at...

, Rossa's Recollections, 1838 to 1898 Mariner"s Harbor, NY, 1898 - Dr. Mark F. RyanMark F. RyanMark Francis Ryan , was an Irish revolutionary, a leading Member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood and author.-Family:...

,Fenian Memories, Edited by T.F. O'Sullivan, M. H. Gill & Son, LTD, Dublin, 1945 - Joseph Denieffe, A Personal Narrative of the Irish Revolutionary Brotherhood, Irish University Press (1969), SBN 7165 0044 2

- Kathleen ClarkeKathleen ClarkeKathleen Clarke, née Daly was a member of Cumann na mBan, and one of very few privy to the plans of the Easter Rising in 1916. She was the wife of Tom Clarke and sister to Ned Daly, both of whom would be executed for their part in the Rebellion...

, Revolutionary Woman: My Fight for Ireland's Freedom, O'Brien Press, Dublin, 1997, ISBN 0 86278 245 7 - Christy Campbell, Fenian Fire: The British Government Plot to Assassinate Queen Victoria, HarperCollins, London, 2002, ISBN 0 00 710483 9

- Marta Ramón, A Provisional Dictator: James Stephens and the Fenian Movement, University College Dublin Press (2007), ISBN 978 1 904558 64 4

- Dennis Gwynn, Young Ireland and 1848, Cork University Press 1949