Double Heroides

Encyclopedia

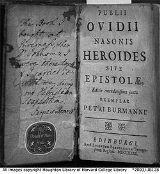

The Double Heroides are a set of six epistolary poems allegedly composed by Ovid

in Latin

elegiac couplet

s, following the fifteen poems of his Heroides

, and numbered 16 to 21 in modern scholarly editions. These six poems present three separate exchanges of paired epistles: one each from a heroic lover from Greek

or Roman mythology

to his absent beloved, and one from the heroine in return. Ovid's authorship is uncertain.

Ovid

Publius Ovidius Naso , known as Ovid in the English-speaking world, was a Roman poet who is best known as the author of the three major collections of erotic poetry: Heroides, Amores, and Ars Amatoria...

in Latin

Latin

Latin is an Italic language originally spoken in Latium and Ancient Rome. It, along with most European languages, is a descendant of the ancient Proto-Indo-European language. Although it is considered a dead language, a number of scholars and members of the Christian clergy speak it fluently, and...

elegiac couplet

Elegiac couplet

The elegiac couplet is a poetic form used by Greek lyric poets for a variety of themes usually of smaller scale than the epic. Roman poets, particularly Ovid, adopted the same form in Latin many years later...

s, following the fifteen poems of his Heroides

Heroides

The Heroides , or Epistulae Heroidum , are a collection of fifteen epistolary poems composed by Ovid in Latin elegiac couplets, and presented as though written by a selection of aggrieved heroines of Greek and Roman mythology, in address to their heroic lovers who have in some way mistreated,...

, and numbered 16 to 21 in modern scholarly editions. These six poems present three separate exchanges of paired epistles: one each from a heroic lover from Greek

Greek mythology

Greek mythology is the body of myths and legends belonging to the ancient Greeks, concerning their gods and heroes, the nature of the world, and the origins and significance of their own cult and ritual practices. They were a part of religion in ancient Greece...

or Roman mythology

Roman mythology

Roman mythology is the body of traditional stories pertaining to ancient Rome's legendary origins and religious system, as represented in the literature and visual arts of the Romans...

to his absent beloved, and one from the heroine in return. Ovid's authorship is uncertain.

The Collection

The single Heroides (1-15) are not listed here: see the relevant section of that article for the single epistles. The paired epistles are written as exchanges between the following heroes and heroines:- XVI. ParisParis (mythology)Paris , the son of Priam, king of Troy, appears in a number of Greek legends. Probably the best-known was his elopement with Helen, queen of Sparta, this being one of the immediate causes of the Trojan War...

to Helen, trying to persuade her to leave her husband, MenelausMenelausMenelaus may refer to;*Menelaus, one of the two most known Atrides, a king of Sparta and son of Atreus and Aerope*Menelaus on the Moon, named after Menelaus of Alexandria.*Menelaus , brother of Ptolemy I Soter...

, and go with him to TroyTroyTroy was a city, both factual and legendary, located in northwest Anatolia in what is now Turkey, southeast of the Dardanelles and beside Mount Ida... - XVII. Helen’s reply to ParisParis (mythology)Paris , the son of Priam, king of Troy, appears in a number of Greek legends. Probably the best-known was his elopement with Helen, queen of Sparta, this being one of the immediate causes of the Trojan War...

, revealing her readiness to leave MenelausMenelausMenelaus may refer to;*Menelaus, one of the two most known Atrides, a king of Sparta and son of Atreus and Aerope*Menelaus on the Moon, named after Menelaus of Alexandria.*Menelaus , brother of Ptolemy I Soter...

for him - XVIII. LeanderHero and LeanderHero and Leander is a Byzantine myth, relating the story of Hērō and like "hero" in English), a priestess of Aphrodite who dwelt in a tower in Sestos on the European side of the Dardanelles, and Leander , a young man from Abydos on the opposite side of the strait. Leander fell in love with Hero...

to Hero, on his love for her - XIX. HeroHero and LeanderHero and Leander is a Byzantine myth, relating the story of Hērō and like "hero" in English), a priestess of Aphrodite who dwelt in a tower in Sestos on the European side of the Dardanelles, and Leander , a young man from Abydos on the opposite side of the strait. Leander fell in love with Hero...

’s reply to Leander, on her love for him - XX. AcontiusAcontiusAcontius , was in Greek mythology a beautiful youth of the island of Ceos, the hero of a love-story told by Callimachus in a poem now lost, which forms the subject of two of Ovid's Heroides . During the festival of Artemis at Delos, Acontius saw Cydippe, a well-born Athenian maiden of whom he was...

to CydippeCydippeThe name Cydippe is attributed to four individuals in Greek mythology.*Cydippe was the mother of Cleobis and Biton. Cydippe, a priestess of Hera, was on her way to a festival in the goddess' honor. The oxen which were to pull her cart were overdue and her sons, Biton and Cleobis pulled the cart...

, on his love for her, reminding her of her commitment to marry him - XXI. CydippeCydippeThe name Cydippe is attributed to four individuals in Greek mythology.*Cydippe was the mother of Cleobis and Biton. Cydippe, a priestess of Hera, was on her way to a festival in the goddess' honor. The oxen which were to pull her cart were overdue and her sons, Biton and Cleobis pulled the cart...

’s reply to AcontiusAcontiusAcontius , was in Greek mythology a beautiful youth of the island of Ceos, the hero of a love-story told by Callimachus in a poem now lost, which forms the subject of two of Ovid's Heroides . During the festival of Artemis at Delos, Acontius saw Cydippe, a well-born Athenian maiden of whom he was...

, agreeing to marry him

Selected bibliography

For further references specifically relating to that subject, please see the single Heroides bibliography.- Anderson, W. S. (1973) “The Heroides”, in J. W. Binns (ed.) Ovid (London and Boston): 49-83.

- Barchiesi, A. (1995) Review of Hintermeier (1993), Journal of Roman Studies (JRS) 85: 325-7.

- ___. (1999) “Vers une histoire à rebours de l'élégie latine: Les Héroides 'Doubles' (16–21)”, in A. Deremetz and J. Fabre-Serris, eds., Élégie et Épopée dans la Poésie ovidienne (Héroides et Amours): En Hommage à Simone Viarre (Lille): 53–67. (=Electronic Antiquity 5.1)

- Beck, M. (1996) Die Epistulae Heroidum XVIII und XIX des Corpus Ovidianum (Paderborn).

- Belfiore, E. (1980–81) “Ovid’s Encomium of Helen”, Classical Journal (CJ) 76.2: 136-48.

- Bessone, F. (2003) “Discussione del mito e polifonia narrativa nelle Heroides. Enone, Paride ed Elena (Ov. Her. 5 e 16-17)”, in M. Guglielmo and E. Bona (eds.), Forme di communicazione nel mondo antico e metamorfosi del mito: dal teatro al romanzo, Culture antiche, studi e testi 17 (Alexandria): 149-85.

- Clark, S. B. (1908) “The Authorship and the Date of the Double Letters in Ovid’s Heroides”, Harvard Studies in Classical Philology (HSCP) 19: 121-55.

- Courtney, E. (1965) “Ovidian and Non-Ovidian Heroides”, Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies of the University of London (BICS) 12: 63-6.

- ___. (1998) “Echtheitskritik: Ovidian and Non-Ovidian Heroides Again”, CJ 93: 157-66.

- Cucchiarelli, A. (1995) “‘Ma il giudice delle dee non era un pastore?’ Reticenze e arte retorica di Paride (Ov. Her. 16)”, Materiali e discussioni per l'analisi dei testi classici (MD) 34: 135-152.

- Drinkwater, M. (2003) Epic and Elegy in Ovid’s Heroides: Paris, Helen, and Homeric Intertext. Diss. Duke University.

- Farrell, J. (1998) “Reading and Writing the Heroides”, Harvard Studies in Classical Philology (HSCP) 98: 307-338.

- Hardie, P. R. (2002) Ovid's Poetics of Illusion (Cambridge).

- Jacobson, H. (1974) Ovid's Heroides (Princeton).

- Jolivet, J.-C. (2001) Allusion et fiction epistolaire dans Les Heroïdes: Recherches sur l'intertextualité ovidienne, Collection de l' École Française de Rome 289 (Rome).

- Kenney, E. J. (1979) “Two Disputed Passages in the Heroides”, Classical Quarterly (CQ) 29: 394-431.

- ___. (1995) “‘Dear Helen . . .’: The Pithanotate Prophasis?”, Papers of the Leeds Latin Seminar (PLLS) 8: 187-207.

- ___. (ed.) (1996) Ovid Heroides XVI-XXI (Cambridge).

- ___. (1999) “Ut erat novator: Anomaly, Innovation and Genre in Ovid, Heroides 16-21”, in J. N. Adams and R. G. Mayer (eds.) Aspects of the Language of Latin Poetry, Proceedings of the British Academy 93 (Oxford): 401-14.

- Knox, P. E. (1986) “Ovid's Medea and the Authenticity of Heroides 12”, Harvard Studies in Classical Philology (HSCP) 90: 207-23.

- ___. (ed.) (1995) Ovid: Heroides. Select Epistles (Cambridge).

- ___. (2000) Review of Beck (1996), Gnomon 72: 405-8.

- ___. (2002) “The Heroides: Elegiac Voices”, in B. W. Boyd (ed.) Brill's Companion to Ovid (Leiden): 117-39.

- Michalopoulos, A. N. (2006) Ovid Heroides 16 & 17: Introduction, Text and Commentary (Cambridge).

- Nesholm, E. (2005) Rhetoric and Epistolary Exchange in Ovid’s Heroides 16-21. Diss. University of Washington.

- Rosati, G. (1991) “Protesilao, Paride, e l’amante elegiaco: un modello omerico in Ovidio”, Maia 43.2: 103-14.

- ___. (1992) “L’elegia al femminile: le Heroides di Ovidio (e altre heroides)”, Materiali e discussioni per l'analisi dei testi classici (MD) 29: 71-94.

- Rosenmeyer, P. A. (1997) “Ovid’s Heroides and Tristia: Voices from Exile”, Ramus 26.1: 29-56.

- Thompson, P. A. M. (1989) Ovid, Heroides 20 and 21, Commentary with Introduction. Diss. University of Oxford.

- ___. (1993) “Notes on Ovid, Heroides 20 and 21”, Classical Quarterly (CQ) 43: 258-65.

- Tracy, V. A. (1971) “The Authenticity of Heroides 16-21”, Classical Journal (CJ) 66.4: 328-330.

- Viarre, S. (1987) “Des poèmes d’Homère aux ‘Heroïdes’ d’Ovide: Le récit épique et son interpretation élégiaque”, Bulletin de l’association Guillaume Budé Ser. 4: 3.