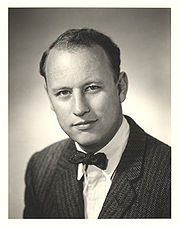

Donald S. Fredrickson

Encyclopedia

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

medical researcher, principally of the lipid

Lipid metabolism

Lipid metabolism refers to the processes that involve the intercourse and degradation of lipids.The types of lipids involved include:* Bile salts* Cholesterols* Eicosanoids* Glycolipids* Ketone bodies* Fatty acids - see also fatty acid metabolism...

and cholesterol

Cholesterol

Cholesterol is a complex isoprenoid. Specifically, it is a waxy steroid of fat that is produced in the liver or intestines. It is used to produce hormones and cell membranes and is transported in the blood plasma of all mammals. It is an essential structural component of mammalian cell membranes...

metabolism, and director of National Institutes of Health

National Institutes of Health

The National Institutes of Health are an agency of the United States Department of Health and Human Services and are the primary agency of the United States government responsible for biomedical and health-related research. Its science and engineering counterpart is the National Science Foundation...

and subsequently the Howard Hughes Medical Institute

Howard Hughes Medical Institute

Howard Hughes Medical Institute is a United States non-profit medical research organization based in Chevy Chase, Maryland. It was founded by the American businessman Howard Hughes in 1953. It is one of the largest private funding organizations for biological and medical research in the United...

.

Biography

Fredrickson was born in Canon City, ColoradoCañon City, Colorado

The City of Cañon City is a Home Rule Municipality that is the county seat and the most populous city of Fremont County, State of Colorado. The United States Census Bureau estimated that the city population was 16,000 in 2005. Cañon City is noted for being the location of nine state and four ...

. His father was a lawyer. After high school he commenced medical school

Medical school

A medical school is a tertiary educational institution—or part of such an institution—that teaches medicine. Degree programs offered at medical schools often include Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine, Bachelor/Doctor of Medicine, Doctor of Philosophy, master's degree, or other post-secondary...

at the University of Colorado, but completed his studies at the University of Michigan

University of Michigan

The University of Michigan is a public research university located in Ann Arbor, Michigan in the United States. It is the state's oldest university and the flagship campus of the University of Michigan...

after being transferred there by the army. During a cycling trip in the Netherlands he met his future wife, Priscilla Eekhof, and they married two years later. They would have two sons.

Between 1949 and 1952 he worked as a resident and subsequently as a fellow in internal medicine

Internal medicine

Internal medicine is the medical specialty dealing with the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of adult diseases. Physicians specializing in internal medicine are called internists. They are especially skilled in the management of patients who have undifferentiated or multi-system disease processes...

at the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital (now part of Brigham and Women's Hospital) in Boston. Much of his published work from this period is in the field of endocrinology

Endocrinology

Endocrinology is a branch of biology and medicine dealing with the endocrine system, its diseases, and its specific secretions called hormones, the integration of developmental events such as proliferation, growth, and differentiation and the coordination of...

. Subsequently he spent a year in the laboratory of Ivan Frantz, a cholesterol biochemist, at Massachusetts General Hospital

Massachusetts General Hospital

Massachusetts General Hospital is a teaching hospital and biomedical research facility in the West End neighborhood of Boston, Massachusetts...

.

Lipid research

In 1953 he took up a post at the National Heart Institute, part of the National Institutes of HealthNational Institutes of Health

The National Institutes of Health are an agency of the United States Department of Health and Human Services and are the primary agency of the United States government responsible for biomedical and health-related research. Its science and engineering counterpart is the National Science Foundation...

in Bethesda, Maryland

Bethesda, Maryland

Bethesda is a census designated place in southern Montgomery County, Maryland, United States, just northwest of Washington, D.C. It takes its name from a local church, the Bethesda Meeting House , which in turn took its name from Jerusalem's Pool of Bethesda...

. Initially, he worked with protein chemist and Nobel laureate Christian B. Anfinsen

Christian B. Anfinsen

Christian Boehmer Anfinsen, Jr. was an American biochemist. He shared the 1972 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with Stanford Moore and William Howard Stein for work on ribonuclease, especially concerning the connection between the amino acid sequence and the biologically active conformation...

, and subsequently (with Daniel Steinberg) developed an interest in the metabolism of cholesterol

Cholesterol

Cholesterol is a complex isoprenoid. Specifically, it is a waxy steroid of fat that is produced in the liver or intestines. It is used to produce hormones and cell membranes and is transported in the blood plasma of all mammals. It is an essential structural component of mammalian cell membranes...

and lipoprotein

Lipoprotein

A lipoprotein is a biochemical assembly that contains both proteins and lipids water-bound to the proteins. Many enzymes, transporters, structural proteins, antigens, adhesins, and toxins are lipoproteins...

s, as well as related medical conditions such as Niemann-Pick disease

Niemann-Pick disease

Niemann–Pick disease refers to a group of fatal inherited metabolic disorders that are included in the larger family of lysosomal storage diseases .-Signs and symptoms:Symptoms are related to the organs in which they accumulate...

. His group identified Tangier disease

Tangier disease

Tangier disease is a rare inherited disorder characterized by a severe reduction in the amount of high density lipoprotein , often referred to as "good cholesterol," in the bloodstream.-Diagnosis:...

(HDL deficiency) and cholesteryl ester storage disease

Cholesteryl ester storage disease

Cholesteryl Ester Storage Disease is the late onset phenotype for Lysosomal Acid Lipase Deficiency, a Lysosomal storage disease, which also has an early onset phenotype known as Wolman disease that primarily affects infants. CESD can present in childhood but often goes unrecognized until...

, two inborn errors of cholesterol metabolism. He played a prime role in the identification of several apolipoprotein

Apolipoprotein

Apolipoproteins are proteins that bind lipids to form lipoproteins and transport the lipids through the lymphatic and circulatory systems....

s (proteins that characterise the nature of a blood lipid particle): APOA2

Apolipoprotein A2

Apolipoprotein A2 is an apolipoprotein found in high density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma.It has an approximate molecular weight 17 KDa....

, APOC1

Apolipoprotein C1

Apolipoprotein C-I is a protein component of lipoproteins that in humans is encoded by the APOC1 gene.- Function :The protein encoded by this gene is a member of the apolipoprotein C family. This gene is expressed primarily in the liver, and it is activated when monocytes differentiate into...

, APOC2 and APOC3

Apolipoprotein C3

Apolipoprotein C-III is a protein component of very low density lipoprotein . APOC3 inhibits lipoprotein lipase and hepatic lipase; it is thought to inhibit hepatic uptake of triglyceride-rich particles. The APOA1, APOC3 and APOA4 genes are closely linked in both rat and human genomes...

.

In 1967 Fredrickson co-authored the paper that described the classification of lipoprotein abnormalities in five types, depending on the pattern of lipoprotein electrophoresis

Electrophoresis

Electrophoresis, also called cataphoresis, is the motion of dispersed particles relative to a fluid under the influence of a spatially uniform electric field. This electrokinetic phenomenon was observed for the first time in 1807 by Reuss , who noticed that the application of a constant electric...

; this became known as the Fredrickson classification. It was adopted as the mondial standard by the World Health Organization

World Health Organization

The World Health Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations that acts as a coordinating authority on international public health. Established on 7 April 1948, with headquarters in Geneva, Switzerland, the agency inherited the mandate and resources of its predecessor, the Health...

in 1972. His group also conducted the first trials of pharmacological cholesterol reduction in the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease

Cardiovascular disease

Heart disease or cardiovascular disease are the class of diseases that involve the heart or blood vessels . While the term technically refers to any disease that affects the cardiovascular system , it is usually used to refer to those related to atherosclerosis...

.

Textbooks

From 1960 he worked, with John Stanbury and James WyngaardenJames Wyngaarden

James Barnes Wyngaarden is a U.S. physician, researcher and academic administrator. He is a co-editor of one of the leading internal medicine texts, and served as director of National Institutes of Health between 1982 and 1989. Has four daughters and one son.Wyngaarden is a member of the Royal...

, on several editions of the encyclopedic medical textbook The Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease.

Directorships

Apart from his work in research, Fredrickson was involved in the management of the NHI from an early stage. He was clinical director from 1960 onward and from 1966 general director of NHI. In 1974 he left the NHI (then already the National Heart and Lung Institute) to head the Institute of MedicineInstitute of Medicine

The Institute of Medicine is a not-for-profit, non-governmental American organization founded in 1970, under the congressional charter of the National Academy of Sciences...

of the National Academy of Sciences

United States National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences is a corporation in the United States whose members serve pro bono as "advisers to the nation on science, engineering, and medicine." As a national academy, new members of the organization are elected annually by current members, based on their distinguished and...

. Nine months later he was asked by president Gerald Ford

Gerald Ford

Gerald Rudolph "Jerry" Ford, Jr. was the 38th President of the United States, serving from 1974 to 1977, and the 40th Vice President of the United States serving from 1973 to 1974...

to become head of the National Institutes of Health

National Institutes of Health

The National Institutes of Health are an agency of the United States Department of Health and Human Services and are the primary agency of the United States government responsible for biomedical and health-related research. Its science and engineering counterpart is the National Science Foundation...

, a task he commenced on 1975-06-01.

One of the main issues that occupied him was the controversy over research involving recombinant DNA

Recombinant DNA

Recombinant DNA molecules are DNA sequences that result from the use of laboratory methods to bring together genetic material from multiple sources, creating sequences that would not otherwise be found in biological organisms...

. Already in 1973 there had been scientists urging a ban on such research for environmental reasons. Fredrickson released a guideline that restricted release of genetically modified organisms into the environment, and called into existence a body that would advise on these matters and had to approve any NIH research involving recombinant DNA technology. Fredrickson is credited with restoring confidence in this form of research. A second controversy involved congressional

United States Congress

The United States Congress is the bicameral legislature of the federal government of the United States, consisting of the Senate and the House of Representatives. The Congress meets in the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C....

control over the NIH in general. Some feel that Fredrickson's decision to resign from his position in 1981 was fuelled by these controversies. The recombinant DNA controversy was the subject of a book published by Fredrickson in 2001.

After 1981 Fredrickson was scholar-in-residence at the National Academy of Sciences

United States National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences is a corporation in the United States whose members serve pro bono as "advisers to the nation on science, engineering, and medicine." As a national academy, new members of the organization are elected annually by current members, based on their distinguished and...

for two years, but in 1983 he was recruited to become the vice-president of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute

Howard Hughes Medical Institute

Howard Hughes Medical Institute is a United States non-profit medical research organization based in Chevy Chase, Maryland. It was founded by the American businessman Howard Hughes in 1953. It is one of the largest private funding organizations for biological and medical research in the United...

, a privately-run health research charity. At that stage, the institute was still the owner of the Hughes Aircraft Company, and Fredrickson participated in the negotiations that led to the sale (for $5.2 billion) to General Motors

General Motors

General Motors Company , commonly known as GM, formerly incorporated as General Motors Corporation, is an American multinational automotive corporation headquartered in Detroit, Michigan and the world's second-largest automaker in 2010...

. He made substantial changes to the institute's research programme. He resigned in 1987 when the trustees of the institute discovered that there had been financial malversations under his presidency.

Later years

Fredrickson returned to the NIH, resuming work on lipid diseases and writing for the National Library of Medicine. He participated in the genetic elucidation of Tangier disease, which he had himself described in the 1960s.He was personal physician to Hassan II of Morocco

Hassan II of Morocco

King Hassan II l-ḥasan aṯ-ṯānī, dial. el-ḥasan ettâni); July 9, 1929 – July 23, 1999) was King of Morocco from 1961 until his death in 1999...

, and had a close personal friendship with the king until the latter's death in 1999.

He was found dead, face-down, in his swimming pool

Swimming pool

A swimming pool, swimming bath, wading pool, or simply a pool, is a container filled with water intended for swimming or water-based recreation. There are many standard sizes; the largest is the Olympic-size swimming pool...

in 2002. He is buried in Leiden, the Netherlands.

External links

- The Donald S. Fredrickson Papers, Profiles in Science, National Library of Medicine

- Donald S. Fredrickson Papers (1910-2002) National Library of Medicine finding aid