Core–mantle boundary

Encyclopedia

Geophysics

Geophysics is the physics of the Earth and its environment in space; also the study of the Earth using quantitative physical methods. The term geophysics sometimes refers only to the geological applications: Earth's shape; its gravitational and magnetic fields; its internal structure and...

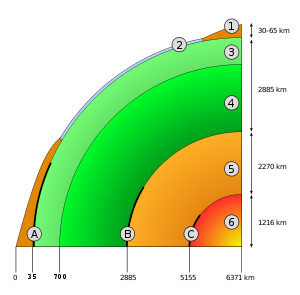

) lies between the Earth's silicate

Silicate

A silicate is a compound containing a silicon bearing anion. The great majority of silicates are oxides, but hexafluorosilicate and other anions are also included. This article focuses mainly on the Si-O anions. Silicates comprise the majority of the earth's crust, as well as the other...

mantle

Mantle (geology)

The mantle is a part of a terrestrial planet or other rocky body large enough to have differentiation by density. The interior of the Earth, similar to the other terrestrial planets, is chemically divided into layers. The mantle is a highly viscous layer between the crust and the outer core....

and its liquid iron

Iron

Iron is a chemical element with the symbol Fe and atomic number 26. It is a metal in the first transition series. It is the most common element forming the planet Earth as a whole, forming much of Earth's outer and inner core. It is the fourth most common element in the Earth's crust...

-nickel

Nickel

Nickel is a chemical element with the chemical symbol Ni and atomic number 28. It is a silvery-white lustrous metal with a slight golden tinge. Nickel belongs to the transition metals and is hard and ductile...

outer core

Outer core

The outer core of the Earth is a liquid layer about 2,266 kilometers thick composed of iron and nickel which lies above the Earth's solid inner core and below its mantle. Its outer boundary lies beneath the Earth's surface...

. This boundary is located at approximately 2900 km of depth beneath the Earth's surface. The boundary is observed via the discontinuity in seismic wave

Seismic wave

Seismic waves are waves of energy that travel through the earth, and are a result of an earthquake, explosion, or a volcano that imparts low-frequency acoustic energy. Many other natural and anthropogenic sources create low amplitude waves commonly referred to as ambient vibrations. Seismic waves...

velocities at that depth. This discontinuity is due to the differences between the acoustic impedances of the solid mantle and the molten outer core. P-wave

P-wave

P-waves are a type of elastic wave, also called seismic waves, that can travel through gases , solids and liquids, including the Earth. P-waves are produced by earthquakes and recorded by seismographs...

velocities are much slower in the outer core than in the deep mantle while S-wave

S-wave

A type of seismic wave, the S-wave, secondary wave, or shear wave is one of the two main types of elastic body waves, so named because they move through the body of an object, unlike surface waves....

s do not exist at all in the liquid portion of the core. Recent evidence suggests a distinct boundary layer directly atop the CMB possibly made of a novel phase of the basic perovskite

Perovskite

A perovskite structure is any material with the same type of crystal structure as calcium titanium oxide , known as the perovskite structure, or XIIA2+VIB4+X2−3 with the oxygen in the face centers. Perovskites take their name from this compound, which was first discovered in the Ural mountains of...

mineralogy of the deep mantle named post-perovskite

Post-perovskite

Post-perovskite is a high-pressure phase of magnesium silicate . It is composed of the prime oxide constituents of the Earth's rocky mantle , and its pressure and temperature for stability imply that it is likely to occur in portions of the lowermost few hundred km of Earth's mantle.The...

. Seismic tomography

Seismic tomography

Seismic tomography is a methodology for estimating the Earth's properties. In the seismology community, seismic tomography is just a part of seismic imaging, and usually has a more specific purpose to estimate properties such as propagating velocities of compressional waves and shear waves . It...

studies have shown significant irregularities within the boundary zone and are suggestive of a possible organized structure as well as the presence of deep mantle plumes.

The ~200 km thick layer of the lower mantle directly above the boundary is referred to as the D′′ ("D double-prime" or "D prime prime") and is sometimes included in discussions regarding the core–mantle boundary zone. The name originates from the mathematician Keith Bullen

Keith Edward Bullen

Keith Edward Bullen FRS was a New Zealand-born mathematician and geophysicist. He is noted for his seismological interpretation of the deep structure of the Earth's mantle and core...

's designations for the Earth's layers. His system was to label each layer alphabetically, A through G, with the crust

Crust (geology)

In geology, the crust is the outermost solid shell of a rocky planet or natural satellite, which is chemically distinct from the underlying mantle...

as 'A' and the inner core

Planetary core

The planetary core consists of the innermost layer of a planet.The core may be composed of solid and liquid layers, while the cores of Mars and Venus are thought to be completely solid as they lack an internally generated magnetic field. In our solar system, core size can range from about 20% to...

as 'G'. In his 1942 publication of his model, the entire lower mantle

Mantle (geology)

The mantle is a part of a terrestrial planet or other rocky body large enough to have differentiation by density. The interior of the Earth, similar to the other terrestrial planets, is chemically divided into layers. The mantle is a highly viscous layer between the crust and the outer core....

was the D layer. In 1950, Bullen found his "D" layer to actually be two different layers. The upper part of the D layer, about 1800 km thick, was renamed D′ (D prime) and the lower part (the bottom 200 km) was named D′′.

The bottom of D′′ has been observed in some regions to be marked by a seismic velocity discontinuity (sometimes known as the 'Gutenberg discontinuity', after German geophysicist Beno Gutenberg

Beno Gutenberg

Beno Gutenberg was a German-American seismologist who made several important contributions to the science...

) which besides features ultra-low velocity zones (ULVZs. ).

See also

- GeophysicsGeophysicsGeophysics is the physics of the Earth and its environment in space; also the study of the Earth using quantitative physical methods. The term geophysics sometimes refers only to the geological applications: Earth's shape; its gravitational and magnetic fields; its internal structure and...

- EarthScopeEarthscopeEarthScope is an earth science program using geological and geophysical techniques to explore the structure and evolution of the North American continent and to understand the processes controlling earthquakes and volcanoes. Thousands of geophysical instruments will comprise a dense grid covering...

- Mohorovičić discontinuityMohorovičić discontinuityThe Mohorovičić discontinuity , usually referred to as the Moho, is the boundary between the Earth's crust and the mantle. Named after the pioneering Croatian seismologist Andrija Mohorovičić, the Moho separates both the oceanic crust and continental crust from underlying mantle...

- Lehmann discontinuityLehmann discontinuityThe Lehmann discontinuity refers to an abrupt increase of P-wave and S-wave velocities in the vicinity of 220±30 km depth, discovered by seismologist Inge Lehmann. It appears beneath continents, but not usually beneath oceans, and does not readily appear in globally averaged studies...