1733 slave insurrection on St. John

Encyclopedia

The 1733 slave insurrection on St. John in the Danish West Indies

, (now St. John, United States Virgin Islands) started on November 23, 1733 when African slaves from Akwamu

revolted against the owners and managers of the island's plantations. The slave rebellion

was one of the earliest and longest slave revolts in the Americas

. The slaves captured the fort in Coral Bay

and took control of most of the island. The revolt ended in mid-1734 when troops sent from Martinique

defeated the Akwamu.

first occupied the West Indies, they used the indigenous people as slave labor

but disease, overworking, and war wiped out this source of labor. When the Danes claimed Saint John in 1718, there was no available source of labor on the island to work the plantations. Young Danish people could not be persuaded to emigrate

to the West Indies in great enough number to provide a reliable source of labor. Attempts to use indentured servants from Danish prisons as plantation workers were not successful. Failure to procure plantation labor from other sources made importing slaves from Africa the main supply of labor on the Danish West Indies islands. Slave export on ships flying under the Danish flag totaled about 85,000 from 1660 to 1806.

The Danes embarked in the African slave trade in 1657, and by the beginning of the eighteenth century, the Danish West India and Guinea Company had consolidated their slave operation to the vicinity of Accra

on the Guinea

coast. The Akwamu were a dominant tribe in the district of Accra and were known for being "heavy-handed in dealing with the tribes they had conquered." After the Akwamu king died, rival tribes in the area attacked the weakened Akwamu nation, and by 1730 the Akwamu were defeated. In retaliation for years of oppression, many Akwamu people were sold into slavery to the Danes and brought to plantations in the West Indies, including estates on St. John. At the time of the 1733 slave rebellion on St. John, hundreds of Akwamu people were among the slave population on St. John. Approximately 150 Africans were involved in the insurrection, and all of them were Akwamus.

In 1718 the Danish made claim of the island of St. John for the purpose of establishing plantations. One hundred nine plantations with more than 1,000 slaves existed on St. John by the time of the 1733 slave rebellion. Many of St. John's plantations were owned by people from St. Thomas who had estates on that island and did not make their residence on St. John. Instead the absentee landowners hired overseers to manage their land on St. John. The population of African slaves on St. John greatly outnumbered the Europeans inhabitants with 1087 slaves and 206 whites.

In 1718 the Danish made claim of the island of St. John for the purpose of establishing plantations. One hundred nine plantations with more than 1,000 slaves existed on St. John by the time of the 1733 slave rebellion. Many of St. John's plantations were owned by people from St. Thomas who had estates on that island and did not make their residence on St. John. Instead the absentee landowners hired overseers to manage their land on St. John. The population of African slaves on St. John greatly outnumbered the Europeans inhabitants with 1087 slaves and 206 whites.

The Danish West India Company did not provide a strong army for the defense of St. John. Besides the local militia

, the number of soldiers stationed on St. John at the time of the slave revolt numbered at six.

, a severe hurricane, and crop failure from insect infestation; slaves in the West Indies, including on St. John, left their plantations to maroon

. In October, 1733, slaves from the Suhm estate on the eastern part of St. John, from the Company estate, and other plantations around the Coral Bay area went maroon. The Slave Code of 1733 was written to force slaves to be completely obedient to their owners. Penalties for disobedience were severe public punishment including whipping, amputation, or death by hanging. A large section of the code intended to prevent actual marooning and stop slaves from conspiring to set up independent communities.

The stated purpose of the 1733 slave insurrection was to make St. John an Akwamu-ruled nation. These new land owners planned to continue the production of sugar and other crops. African slaves of other tribal origins were to serve as slaves for the Akwamu people. The leader of the revolt was an Akwamu chief, King June, a field slave and foreman on the Sødtmann estate. Other leaders were Kanta, King Bolombo, Prince Aquashie, and Breffu. According to a report by a French planter, Pierre Pannet, the rebel leaders met regularly at night to develop the plan.

Johannes Sødtmann. An hour later, slaves were admitted into the fort at Coral Bay to deliver wood. They had hidden knives in the lots, which they used to kill most of the soldiers at the fort. One soldier, John Gabriel, escaped to St. Thomas and alerted the Danish officials. A group of rebels under the leadership of King June stayed at the fort to maintain control, another group took control of the estates in the Coral Bay area after hearing the signal shots from the fort's cannon. The slaves killed many of the whites on these plantations. The rebel slaves then moved to the north shore of the island. They avoided widespread destruction of property since they intended to take possession of the estates and resume crop production.

located on the central north shore. Landowners John and Lieven Jansen and a group of loyal slaves resisted the attack and held off the advancing rebels with gunfire. The Jansens were able to retreat to their waiting boat and escape to Durloe's Plantation. The loyal Jansen slaves were also able to escape. The rebels looted the Jansen plantation and then moved on to confront the whites held up at Durloe's plantations. The attack on Durloe's plantation was repelled, and many of the planters and their families escaped to St. Thomas.

troops to try to take control from the rebels. With their firepower and troops, by mid-May they had restored planters' rule of the island. The French ships returned to Martinique on June 1, leaving the local militia to track down the remaining rebels. The slave insurrection ended on August 25, 1734 when Sergeant Øttingen captured the remaining maroon rebels.

The loss of life and property from the insurrection caused many St. John landowners to move to St. Croix, a nearby island sold to the Danish by the French in 1733.

Franz Claasen, a loyal slave of the van Stell family, was deeded the Mary Point Estate

for alerting the family to the rebellion and assisting in their escape to St. Thomas. Franz Claasen's land deed was recorded August 20, 1738 by Jacob van Stell, making Claasen the first 'Free Colored' landowner on St. John.

The slave trade ended in the Danish West Indies on January 1, 1803, but slavery continued on the islands. When the slaves in the British West Indies

The slave trade ended in the Danish West Indies on January 1, 1803, but slavery continued on the islands. When the slaves in the British West Indies

were freed in 1838, slaves on St. John began escaping to nearby Tortola

and other British islands. On May 24, 1840, eleven slaves from St. John stole a boat and escaped to Tortola during the night. The eight men (Charles Bryan, James Jacob, Adam [alias Cato], Big David, Henry Law, Paulus, John Curay), and three women (Kitty, Polly, and Katurah) were from the Annaberg plantation

(one) and Leinster Bay (10) estates. Brother Schmitz, the local Moravian missionary

, was sent to Tortola by the St. John police to persuade the slaves to return. After meeting with the Tortola officials and the runaway slaves, Schmitz returned to St. John to relay the slaves' resolve to stay away because of abusive treatment by the overseers on the plantations. After the overseers were replaced, Charles Bryan, his wife Katurah, and James Jacobs returned to work at Leinster Bay. Kitty, Paulus, David, and Adam moved to St. Thomas. Henry Law, Petrus, and Polly remained on Tortola. John Curry relocated to Trinidad. None of runaway slaves were punished.

On July 3, 1848, 114 years after the slave insurrection, enslaved Africans of St. Croix had a non-violent, mass demonstration that forced the Governor-General to declare emancipation

throughout the Danish West Indies.

Danish West Indies

The Danish West Indies or "Danish Antilles", were a colony of Denmark-Norway and later Denmark in the Caribbean. They were sold to the United States in 1916 in the Treaty of the Danish West Indies and became the United States Virgin Islands in 1917...

, (now St. John, United States Virgin Islands) started on November 23, 1733 when African slaves from Akwamu

Akwamu

The Akwamu was a state set up by the Akan people in Ghana which existed in the 17th century and 18th century. Originally immigrating from Bono state, the founders settled in Twifo-Heman. The Akwamu created an expansionist empire in the 16th and 17th century...

revolted against the owners and managers of the island's plantations. The slave rebellion

Slave rebellion

A slave rebellion is an armed uprising by slaves. Slave rebellions have occurred in nearly all societies that practice slavery, and are amongst the most feared events for slaveholders...

was one of the earliest and longest slave revolts in the Americas

Americas

The Americas, or America , are lands in the Western hemisphere, also known as the New World. In English, the plural form the Americas is often used to refer to the landmasses of North America and South America with their associated islands and regions, while the singular form America is primarily...

. The slaves captured the fort in Coral Bay

Coral Bay, United States Virgin Islands

Coral Bay is a town on the island of St. John in the United States Virgin Islands. It is located on the southeastern side of the island. Though it was once the main commercial and population center on the island due to its sheltered harbor, it has fallen from prominence with the introduction of a...

and took control of most of the island. The revolt ended in mid-1734 when troops sent from Martinique

Martinique

Martinique is an island in the eastern Caribbean Sea, with a land area of . Like Guadeloupe, it is an overseas region of France, consisting of a single overseas department. To the northwest lies Dominica, to the south St Lucia, and to the southeast Barbados...

defeated the Akwamu.

Slave trade

When the SpanishSpanish people

The Spanish are citizens of the Kingdom of Spain. Within Spain, there are also a number of vigorous nationalisms and regionalisms, reflecting the country's complex history....

first occupied the West Indies, they used the indigenous people as slave labor

Manual labour

Manual labour , manual or manual work is physical work done by people, most especially in contrast to that done by machines, and also to that done by working animals...

but disease, overworking, and war wiped out this source of labor. When the Danes claimed Saint John in 1718, there was no available source of labor on the island to work the plantations. Young Danish people could not be persuaded to emigrate

Emigrate

Emigrate is a heavy metal band based in New York, led by Richard Z. Kruspe, the lead guitarist of the German band Rammstein.-History:Kruspe started the band in 2005, when Rammstein decided to take a year off from touring and recording...

to the West Indies in great enough number to provide a reliable source of labor. Attempts to use indentured servants from Danish prisons as plantation workers were not successful. Failure to procure plantation labor from other sources made importing slaves from Africa the main supply of labor on the Danish West Indies islands. Slave export on ships flying under the Danish flag totaled about 85,000 from 1660 to 1806.

The Danes embarked in the African slave trade in 1657, and by the beginning of the eighteenth century, the Danish West India and Guinea Company had consolidated their slave operation to the vicinity of Accra

Accra

Accra is the capital and largest city of Ghana, with an urban population of 1,658,937 according to the 2000 census. Accra is also the capital of the Greater Accra Region and of the Accra Metropolitan District, with which it is coterminous...

on the Guinea

Guinea

Guinea , officially the Republic of Guinea , is a country in West Africa. Formerly known as French Guinea , it is today sometimes called Guinea-Conakry to distinguish it from its neighbour Guinea-Bissau. Guinea is divided into eight administrative regions and subdivided into thirty-three prefectures...

coast. The Akwamu were a dominant tribe in the district of Accra and were known for being "heavy-handed in dealing with the tribes they had conquered." After the Akwamu king died, rival tribes in the area attacked the weakened Akwamu nation, and by 1730 the Akwamu were defeated. In retaliation for years of oppression, many Akwamu people were sold into slavery to the Danes and brought to plantations in the West Indies, including estates on St. John. At the time of the 1733 slave rebellion on St. John, hundreds of Akwamu people were among the slave population on St. John. Approximately 150 Africans were involved in the insurrection, and all of them were Akwamus.

Danish occupation of St. John

The Danish West India Company did not provide a strong army for the defense of St. John. Besides the local militia

Militia

The term militia is commonly used today to refer to a military force composed of ordinary citizens to provide defense, emergency law enforcement, or paramilitary service, in times of emergency without being paid a regular salary or committed to a fixed term of service. It is a polyseme with...

, the number of soldiers stationed on St. John at the time of the slave revolt numbered at six.

Marooning

In 1733, in response to harsh living conditions from droughtDrought

A drought is an extended period of months or years when a region notes a deficiency in its water supply. Generally, this occurs when a region receives consistently below average precipitation. It can have a substantial impact on the ecosystem and agriculture of the affected region...

, a severe hurricane, and crop failure from insect infestation; slaves in the West Indies, including on St. John, left their plantations to maroon

Maroon (people)

Maroons were runaway slaves in the West Indies, Central America, South America, and North America, who formed independent settlements together...

. In October, 1733, slaves from the Suhm estate on the eastern part of St. John, from the Company estate, and other plantations around the Coral Bay area went maroon. The Slave Code of 1733 was written to force slaves to be completely obedient to their owners. Penalties for disobedience were severe public punishment including whipping, amputation, or death by hanging. A large section of the code intended to prevent actual marooning and stop slaves from conspiring to set up independent communities.

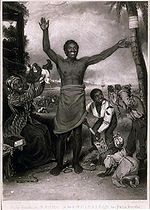

Slave revolt

The Akwamus on St. John did not see themselves as slaves, since in their homeland many were nobles, wealthy merchants or other powerful members of their society; so marooning was a natural response to their intolerable living conditions.The stated purpose of the 1733 slave insurrection was to make St. John an Akwamu-ruled nation. These new land owners planned to continue the production of sugar and other crops. African slaves of other tribal origins were to serve as slaves for the Akwamu people. The leader of the revolt was an Akwamu chief, King June, a field slave and foreman on the Sødtmann estate. Other leaders were Kanta, King Bolombo, Prince Aquashie, and Breffu. According to a report by a French planter, Pierre Pannet, the rebel leaders met regularly at night to develop the plan.

Events on November 23, 1733

The 1733 slave insurrection started open acts of rebellion on November 23, 1733 at the Coral Bay plantation owned by MagistrateMagistrate

A magistrate is an officer of the state; in modern usage the term usually refers to a judge or prosecutor. This was not always the case; in ancient Rome, a magistratus was one of the highest government officers and possessed both judicial and executive powers. Today, in common law systems, a...

Johannes Sødtmann. An hour later, slaves were admitted into the fort at Coral Bay to deliver wood. They had hidden knives in the lots, which they used to kill most of the soldiers at the fort. One soldier, John Gabriel, escaped to St. Thomas and alerted the Danish officials. A group of rebels under the leadership of King June stayed at the fort to maintain control, another group took control of the estates in the Coral Bay area after hearing the signal shots from the fort's cannon. The slaves killed many of the whites on these plantations. The rebel slaves then moved to the north shore of the island. They avoided widespread destruction of property since they intended to take possession of the estates and resume crop production.

Accounts of the rebel attacks

After gaining control of the Suhm, Sødtmann, and Company estates, the rebels began to spread out over the rest of the island. The Akwamus attacked the Cinnamon Bay PlantationCinnamon Bay Plantation

Cinnamon Bay Plantation is an approximately property situated on the north central coast of Saint John in the United States Virgin Islands adjacent to Cinnamon Bay. The land, part of Virgin Islands National Park, was added to the United States National Register of Historic Places on July 11, 1978...

located on the central north shore. Landowners John and Lieven Jansen and a group of loyal slaves resisted the attack and held off the advancing rebels with gunfire. The Jansens were able to retreat to their waiting boat and escape to Durloe's Plantation. The loyal Jansen slaves were also able to escape. The rebels looted the Jansen plantation and then moved on to confront the whites held up at Durloe's plantations. The attack on Durloe's plantation was repelled, and many of the planters and their families escaped to St. Thomas.

End of the rebellion and the aftermath

Two French ships arrived at St. John on April 23, 1734 with several hundred French and SwissSwitzerland

Switzerland name of one of the Swiss cantons. ; ; ; or ), in its full name the Swiss Confederation , is a federal republic consisting of 26 cantons, with Bern as the seat of the federal authorities. The country is situated in Western Europe,Or Central Europe depending on the definition....

troops to try to take control from the rebels. With their firepower and troops, by mid-May they had restored planters' rule of the island. The French ships returned to Martinique on June 1, leaving the local militia to track down the remaining rebels. The slave insurrection ended on August 25, 1734 when Sergeant Øttingen captured the remaining maroon rebels.

The loss of life and property from the insurrection caused many St. John landowners to move to St. Croix, a nearby island sold to the Danish by the French in 1733.

Franz Claasen, a loyal slave of the van Stell family, was deeded the Mary Point Estate

Mary Point Estate

Mary Point Estate is a historic property located on the north coast of Saint John, United States Virgin Islands on Mary's Point. The plantation was added to the U.S. National Register of Historic Places on May 22, 1978.-History:...

for alerting the family to the rebellion and assisting in their escape to St. Thomas. Franz Claasen's land deed was recorded August 20, 1738 by Jacob van Stell, making Claasen the first 'Free Colored' landowner on St. John.

British West Indies

The British West Indies was a term used to describe the islands in and around the Caribbean that were part of the British Empire The term was sometimes used to include British Honduras and British Guiana, even though these territories are not geographically part of the Caribbean...

were freed in 1838, slaves on St. John began escaping to nearby Tortola

Tortola

Tortola is the largest and most populated of the British Virgin Islands, a group of islands that form part of the archipelago of the Virgin Islands. Local tradition recounts that Christopher Columbus named it Tortola, meaning "land of the Turtle Dove". Columbus named the island Santa Ana...

and other British islands. On May 24, 1840, eleven slaves from St. John stole a boat and escaped to Tortola during the night. The eight men (Charles Bryan, James Jacob, Adam [alias Cato], Big David, Henry Law, Paulus, John Curay), and three women (Kitty, Polly, and Katurah) were from the Annaberg plantation

Annaberg Historic District

Annaberg Historic District is a historic section of Saint John, United States Virgin Islands where the Annaberg sugar plantation ruins are located. The district is located on the north shore of the island west of Mary's Point in the Maho Bay quarter....

(one) and Leinster Bay (10) estates. Brother Schmitz, the local Moravian missionary

Missionary

A missionary is a member of a religious group sent into an area to do evangelism or ministries of service, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care and economic development. The word "mission" originates from 1598 when the Jesuits sent members abroad, derived from the Latin...

, was sent to Tortola by the St. John police to persuade the slaves to return. After meeting with the Tortola officials and the runaway slaves, Schmitz returned to St. John to relay the slaves' resolve to stay away because of abusive treatment by the overseers on the plantations. After the overseers were replaced, Charles Bryan, his wife Katurah, and James Jacobs returned to work at Leinster Bay. Kitty, Paulus, David, and Adam moved to St. Thomas. Henry Law, Petrus, and Polly remained on Tortola. John Curry relocated to Trinidad. None of runaway slaves were punished.

On July 3, 1848, 114 years after the slave insurrection, enslaved Africans of St. Croix had a non-violent, mass demonstration that forced the Governor-General to declare emancipation

Emancipation

Emancipation means the act of setting an individual or social group free or making equal to citizens in a political society.Emancipation may also refer to:* Emancipation , a champion Australian thoroughbred racehorse foaled in 1979...

throughout the Danish West Indies.