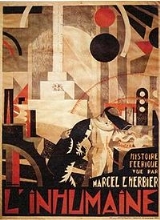

L'Inhumaine

Encyclopedia

L'Inhumaine is a 1924

French drama-science fiction film directed by Marcel L'Herbier

. It was notable for its experimental techniques and for the collaboration of many leading practitioners in the decorative arts, architecture and music. The film gave rise to much controversy on its release.

to make a film in which she would star and for which she would secure partial funding from American financiers. L'Herbier revived a scenario which he had written under the title La Femme de glace; when Leblanc declared this to be too abstract for her liking and for American taste, he enlisted Pierre Mac Orlan

to revise it according to Leblanc's suggestions, and in its new form it became L'Inhumaine. The agreement with Leblanc committed her to provide 50% of the costs (envisaged as FF130,000), and she would distribute and promote the film in the United States under the title The New Enchantment. The remainder of the production costs were met by L'Herbier's own production company Cinégraphic.

The plot of the film was a melodrama with strong elements of fantasy, but from the outset L'Herbier's principal interest lay in the style of filming: he wanted to present "a miscellany of modern art" in which many contributors would bring different creative styles into a single aesthetic goal.

In this respect L'Herbier was exploring ideas similar to those outlined by the critic and film theorist Ricciotto Canudo

who wrote a number of texts about the relationship between cinema and the other arts, proposing that cinema could be seen as "a synthesis of all the arts". L'Herbier also foresaw that his film could provide a prologue or introduction to the major exhibition Exposition des Arts Décoratifs

which was due to open in Paris in 1925. With this in mind, L'Herbier invited leading French practitioners in painting, architecture, fashion, dance and music to collaborate with him (see "Production", below). He described the project as "this fairy story of modern decorative art".

One evening of location shooting became famous (4 October 1924). For the scene of Claire Lescot's concert L'Herbier hired the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées

and invited over 2000 people from the film world and fashionable society to attend in evening dress and to play the part of an unruly audience. Ten cameras were deployed around the theatre to record their reactions to the concert. This included the American pianist George Antheil

performing some of his own dissonant compositions which created a suitably confrontational mood, and when Georgette Leblanc appeared on stage the audience responded with the required tumult of whistles, applause and protests, as well as some scuffles. The audience is said to have included Erik Satie

, Pablo Picasso

, Man Ray

, Léon Blum

, James Joyce

, Ezra Pound

and the Prince of Monaco

.

An impressive range of practitioners in different fields of the arts worked on the film, meeting L'Herbier's ambition of creating a film which united many forms of artistic expression. Four designers contributed to the sets. The painter Fernand Léger

created the mechanical laboratory of Einar Norsen. The architect Robert Mallet-Stevens

designed the exteriors of the houses of Norsen and Claire Lescot, with strong cubist elements. Alberto Cavalcanti

and Claude Autant-Lara

, soon to be directing their own films, both had a background in design; Autant-Lara was responsible for the winter-garden set and the funeral vault, while Cavalcanti designed the geometric dining hall for Claire's party, with its dining-table set on an island in the middle of a pool. Costumes were designed by Paul Poiret

, furniture by Pierre Chareau

and Michel Dufet, jewellery by Raymond Templier, and other "objets" by René Lalique

and Jean Puiforcat. The choreographed scenes were provided by Jean Borlin and the Ballets Suédois

. To bind the whole together L'Herbier commissioned the young Darius Milhaud

to write a score with extensive use of percussion, to which the images were to be edited. (This musical score which was central to L'Herbier's conception of the film has not survived.)

The final sequence of the film, in which Claire is 'resurrected', is an elaborate exercise in rapid cutting, whose expressive possibilites had recently been demonstrated in La Roue

. In addition to the juxtaposition and rhythmic repetition of images, L'Herbier interspersed frames of bright colours, intending to create counterpoint to the music of Milhaud and "to make the light sing".

"At each screening, spectators insulted each other, and there were as many frenzied partisans of the film as there were furious opponents. It was amid genuine uproar that, at every performance, there passed across the screen the multicoloured and syncopated images with which the film ends. Women, with hats askew, demanded their money back; men, with their faces screwed up, tumbled out on to the pavement where sometimes fist-fights continued."

Criticism was levelled at the old-fashioned scenario and at the inexpressive performances of the principal actors, but the most contentious aspects were the film's visual and technical innovations. According to the critic Léon Moussinac, "There are many inventions, but they count too much for themselves and not enough for the film"

Many film historians and critics have ridiculed L'Inhumaine as misguided attempt to celebrate film as art or to reconcile the popular and the élitist. On the other hand, it was precisely the originality and daring of L'Herbier's concept which won the enthusiasm of the film's admirers, such as the architect Adolf Loos

: "It is a brilliant song on the greatness of modern technique. ...The final images of L'Inhumaine surpass the imagination. As you emerge from seeing it, you have the impression of having lived through the moment of birth of a new art." A modern commentator has echoed this view more concisely in describing the film as "fabulously inventive".

L'Herbier had always wanted the film to provide to the world a showcase for contemporary decorative arts in France (as well as its cinema) and the film was duly presented in a number of cities abroad (New York, Barcelona, Geneva, London, Brussels, Warsaw, Shanghai, Tokyo). It at least succeeded in drawing more measured responses from those audiences.

After its initial release L'Inhumaine was largely forgotten for many years, until a revival in Paris in 1968 attracted interest from new audiences. A restoration of the film was undertaken in 1972, and in 1975 it was successfully shown as the opening event in an exhibition commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Exposition des Arts Décoratifs.

In 1987 it was screened out of competition at the Cannes Film Festival

.

1924 in film

-Events:* Entertainment entrepreneur Marcus Loew gained control of Metro Pictures, Goldwyn Pictures Corporation and Louis B. Mayer Pictures to create Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer...

French drama-science fiction film directed by Marcel L'Herbier

Marcel L'Herbier

Marcel L'Herbier, Légion d'honneur, was a French film-maker, who achieved prominence as an avant-garde theorist and imaginative practitioner with a series of silent films in the 1920s. His career as a director continued until the 1950s and he made more than 40 feature films in total...

. It was notable for its experimental techniques and for the collaboration of many leading practitioners in the decorative arts, architecture and music. The film gave rise to much controversy on its release.

Background

In 1923, while seeking to recover his health after a bout of typhoid, and his fortunes following the collapse of his film adaptation of Résurrection, Marcel L'Herbier received a proposal from his old friend the opera singer Georgette LeblancGeorgette Leblanc

Georgette Leblanc was a French operatic soprano, actress, author, and the sister of novelist Maurice Leblanc. She became particularly associated with the works of Jules Massenet and was an admired interpreter of the title role in Bizet's Carmen...

to make a film in which she would star and for which she would secure partial funding from American financiers. L'Herbier revived a scenario which he had written under the title La Femme de glace; when Leblanc declared this to be too abstract for her liking and for American taste, he enlisted Pierre Mac Orlan

Pierre Mac Orlan

Pierre Mac Orlan, sometimes written MacOrlan, was a French novelist and songwriter.His novel Quai des Brumes was the source for Marcel Carné's 1938 film of the same name, starring Jean Gabin...

to revise it according to Leblanc's suggestions, and in its new form it became L'Inhumaine. The agreement with Leblanc committed her to provide 50% of the costs (envisaged as FF130,000), and she would distribute and promote the film in the United States under the title The New Enchantment. The remainder of the production costs were met by L'Herbier's own production company Cinégraphic.

The plot of the film was a melodrama with strong elements of fantasy, but from the outset L'Herbier's principal interest lay in the style of filming: he wanted to present "a miscellany of modern art" in which many contributors would bring different creative styles into a single aesthetic goal.

In this respect L'Herbier was exploring ideas similar to those outlined by the critic and film theorist Ricciotto Canudo

Ricciotto Canudo

Ricciotto Canudo was an early Italian film theoretician who lived primarily in France. He saw cinema as "plastic art in motion". He gave cinema the label "the Seventh Art", which is still current in French....

who wrote a number of texts about the relationship between cinema and the other arts, proposing that cinema could be seen as "a synthesis of all the arts". L'Herbier also foresaw that his film could provide a prologue or introduction to the major exhibition Exposition des Arts Décoratifs

Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes

The International Exposition of Modern Industrial and Decorative Arts was a World's fair held in Paris, France, from April to October 1925. The term "Art Deco" was derived by shortening the words Arts Décoratifs, in the title of this exposition, but not until the late 1960s by British art critic...

which was due to open in Paris in 1925. With this in mind, L'Herbier invited leading French practitioners in painting, architecture, fashion, dance and music to collaborate with him (see "Production", below). He described the project as "this fairy story of modern decorative art".

Synopsis

Famous singer Claire Lescot, who lives on the outskirts of Paris, is courted by many men, including a maharajah, Djorah de Nopur, and a young Swedish scientist, Einar Norsen. At her lavish parties she enjoys their amorous attentions but she remains emotionally aloof and heartlessly taunts them. When she is told that Norsen has killed himself because of her, she shows no feelings. At her next concert she is booed by an audience outraged at her coldness. She visits the vault in which Norsen's body lies, and as she admits her feelings for him she discovers that he is alive; his death was feigned. Djorah is jealous of their new relationship and causes Claire to be bitten by a poisonous snake. Her body is brought to Norsen's laboratory, where he, by means of his scientific inventions, restores Claire to life.Cast

- Georgette LeblancGeorgette LeblancGeorgette Leblanc was a French operatic soprano, actress, author, and the sister of novelist Maurice Leblanc. She became particularly associated with the works of Jules Massenet and was an admired interpreter of the title role in Bizet's Carmen...

as Claire Lescot - Jaque CatelainJaque CatelainJaque Catelain was a French actor who came to prominence in silent films of the 1920s, and who continued acting in films and on stage until the 1950s. He also wrote and directed two silent films himself, and he was a capable artist and musician. He had a close association with the director Marcel...

as Einar Norsen - Léonid Walter de Malte as Wladimir Kranine

- Fred Kellerman as Frank Mahler

- Philippe HériatPhilippe HériatPhilippe Hériat was a multi-talented French novelist, playwright and actor.-Biography:Born Raymond Gérard Payelle, he studied with film director René Clair and in 1920 made his debut in silent film...

as Djorah de Nopur - Marcelle PradotMarcelle PradotMarcelle Pradot was a French actress who worked principally in silent films. She was born at Montmorency, Val-d'Oise, near Paris. At the age of 18 while she was taking classes in dancing and singing in Paris, she was asked by Marcel L'Herbier to appear in his film Le Bercail...

as The simpleton

Production

Filming began in September 1923 at the Joinville studios in Paris and had to be carried on at great speed because Georgette Leblanc was committed to return to America in mid-October for a concert tour. L'Herbier often continued shooting through the night, making intense demands on his cast and crew. In the event, Leblanc had to leave before everything was finished and some scenes could only be completed when she returned to Paris in spring 1924.One evening of location shooting became famous (4 October 1924). For the scene of Claire Lescot's concert L'Herbier hired the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées

Théâtre des Champs-Élysées

The Théâtre des Champs-Élysées is a theatre at 15 avenue Montaigne. Despite its name, the theatre is not on the Champs-Élysées but nearby in another part of the 8th arrondissement of Paris....

and invited over 2000 people from the film world and fashionable society to attend in evening dress and to play the part of an unruly audience. Ten cameras were deployed around the theatre to record their reactions to the concert. This included the American pianist George Antheil

George Antheil

George Antheil was an American avant-garde composer, pianist, author and inventor. A self-described "Bad Boy of Music", his modernist compositions amazed and appalled listeners in Europe and the US during the 1920s with their cacophonous celebration of mechanical devices.Returning permanently to...

performing some of his own dissonant compositions which created a suitably confrontational mood, and when Georgette Leblanc appeared on stage the audience responded with the required tumult of whistles, applause and protests, as well as some scuffles. The audience is said to have included Erik Satie

Erik Satie

Éric Alfred Leslie Satie was a French composer and pianist. Satie was a colourful figure in the early 20th century Parisian avant-garde...

, Pablo Picasso

Pablo Picasso

Pablo Diego José Francisco de Paula Juan Nepomuceno María de los Remedios Cipriano de la Santísima Trinidad Ruiz y Picasso known as Pablo Ruiz Picasso was a Spanish expatriate painter, sculptor, printmaker, ceramicist, and stage designer, one of the greatest and most influential artists of the...

, Man Ray

Man Ray

Man Ray , born Emmanuel Radnitzky, was an American artist who spent most of his career in Paris, France. Perhaps best described simply as a modernist, he was a significant contributor to both the Dada and Surrealist movements, although his ties to each were informal...

, Léon Blum

Léon Blum

André Léon Blum was a French politician, usually identified with the moderate left, and three times the Prime Minister of France.-First political experiences:...

, James Joyce

James Joyce

James Augustine Aloysius Joyce was an Irish novelist and poet, considered to be one of the most influential writers in the modernist avant-garde of the early 20th century...

, Ezra Pound

Ezra Pound

Ezra Weston Loomis Pound was an American expatriate poet and critic and a major figure in the early modernist movement in poetry...

and the Prince of Monaco

Prince of Monaco

The Reigning Prince or Princess of Monaco is the sovereign monarch and head of state of the Principality of Monaco. All Princes or Princesses thus far have taken the name of the House of Grimaldi, but have belonged to various other houses in male line...

.

An impressive range of practitioners in different fields of the arts worked on the film, meeting L'Herbier's ambition of creating a film which united many forms of artistic expression. Four designers contributed to the sets. The painter Fernand Léger

Fernand Léger

Joseph Fernand Henri Léger was a French painter, sculptor, and filmmaker. In his early works he created a personal form of Cubism which he gradually modified into a more figurative, populist style...

created the mechanical laboratory of Einar Norsen. The architect Robert Mallet-Stevens

Robert Mallet-Stevens

Robert Mallet-Stevens was a French architect and designer. Along with Le Corbusier he is widely regarded as the most influential figure in French architecture in the period between the two World Wars....

designed the exteriors of the houses of Norsen and Claire Lescot, with strong cubist elements. Alberto Cavalcanti

Alberto Cavalcanti

Alberto de Almeida Cavalcanti was a Brazilian-born film director and producer.-Early life:Cavalcanti was born in Rio de Janeiro, the son of a prominent mathematician. He was a precociously intelligent child, and by the age of 15 was studying law at university. Following an argument with a...

and Claude Autant-Lara

Claude Autant-Lara

Claude Autant-Lara , was a French film director and later Member of the European Parliament .-Biography:...

, soon to be directing their own films, both had a background in design; Autant-Lara was responsible for the winter-garden set and the funeral vault, while Cavalcanti designed the geometric dining hall for Claire's party, with its dining-table set on an island in the middle of a pool. Costumes were designed by Paul Poiret

Paul Poiret

Paul Poiret was a French fashion designer. His contributions to twentieth-century fashion have been likened to Picasso's contributions to twentieth-century art.-Early life and career:...

, furniture by Pierre Chareau

Pierre Chareau

Pierre Chareau was a French architect and designer.-Early life:Chareau was born in Le Havre, France. He went to the École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris by the time he was 17.-Work:...

and Michel Dufet, jewellery by Raymond Templier, and other "objets" by René Lalique

René Lalique

René Jules Lalique was a French glass designer known for his creations of perfume bottles, vases, jewellery, chandeliers, clocks and automobile hood ornaments. He was born in the French village of Ay on 6 April 1860 and died 5 May 1945...

and Jean Puiforcat. The choreographed scenes were provided by Jean Borlin and the Ballets Suédois

Ballets Suédois

The Ballets suédois was a predominantly Swedish dance ensemble that, under the direction of Rolf de Maré , performed throughout Europe and the United States between 1920 and 1925, rightfully earning the reputation as a “synthesis of modern art” .The Ballets suédois created pieces that negotiated...

. To bind the whole together L'Herbier commissioned the young Darius Milhaud

Darius Milhaud

Darius Milhaud was a French composer and teacher. He was a member of Les Six—also known as The Group of Six—and one of the most prolific composers of the 20th century. His compositions are influenced by jazz and make use of polytonality...

to write a score with extensive use of percussion, to which the images were to be edited. (This musical score which was central to L'Herbier's conception of the film has not survived.)

The final sequence of the film, in which Claire is 'resurrected', is an elaborate exercise in rapid cutting, whose expressive possibilites had recently been demonstrated in La Roue

La Roue

La Roue is a French silent film, directed by Abel Gance, who also directed Napoléon and J'accuse!. It was released in 1923. Originally 32 reels in length , the current reconstruction runs 20 reels...

. In addition to the juxtaposition and rhythmic repetition of images, L'Herbier interspersed frames of bright colours, intending to create counterpoint to the music of Milhaud and "to make the light sing".

Reception

L'Inhumaine received its first public screenings in November 1924, and its reception with the public and with critics was largely negative. It also became a financial disaster for L'Herbier's production company Cinégraphic. One of the film's stars drew a vivid picture of the impact which it had among Parisian audiences during its run at the Madeleine-Cinéma:"At each screening, spectators insulted each other, and there were as many frenzied partisans of the film as there were furious opponents. It was amid genuine uproar that, at every performance, there passed across the screen the multicoloured and syncopated images with which the film ends. Women, with hats askew, demanded their money back; men, with their faces screwed up, tumbled out on to the pavement where sometimes fist-fights continued."

Criticism was levelled at the old-fashioned scenario and at the inexpressive performances of the principal actors, but the most contentious aspects were the film's visual and technical innovations. According to the critic Léon Moussinac, "There are many inventions, but they count too much for themselves and not enough for the film"

Many film historians and critics have ridiculed L'Inhumaine as misguided attempt to celebrate film as art or to reconcile the popular and the élitist. On the other hand, it was precisely the originality and daring of L'Herbier's concept which won the enthusiasm of the film's admirers, such as the architect Adolf Loos

Adolf Loos

Adolf Franz Karl Viktor Maria Loos was a Moravian-born Austro-Hungarian architect. He was influential in European Modern architecture, and in his essay Ornament and Crime he repudiated the florid style of the Vienna Secession, the Austrian version of Art Nouveau...

: "It is a brilliant song on the greatness of modern technique. ...The final images of L'Inhumaine surpass the imagination. As you emerge from seeing it, you have the impression of having lived through the moment of birth of a new art." A modern commentator has echoed this view more concisely in describing the film as "fabulously inventive".

L'Herbier had always wanted the film to provide to the world a showcase for contemporary decorative arts in France (as well as its cinema) and the film was duly presented in a number of cities abroad (New York, Barcelona, Geneva, London, Brussels, Warsaw, Shanghai, Tokyo). It at least succeeded in drawing more measured responses from those audiences.

After its initial release L'Inhumaine was largely forgotten for many years, until a revival in Paris in 1968 attracted interest from new audiences. A restoration of the film was undertaken in 1972, and in 1975 it was successfully shown as the opening event in an exhibition commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Exposition des Arts Décoratifs.

In 1987 it was screened out of competition at the Cannes Film Festival

1987 Cannes Film Festival

- Jury :*Yves Montand*Danièle Heymann*Elem Klimov*Gérald Calderon*Jeremy Thomas*Jerzy Skolimowski*Nicola Piovani*Norman Mailer*Theo Angelopoulos-Feature film competition:...

.

Further reading

- Abel, Richard. French Cinema: the First Wave 1915-1929. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 1984. pp.383-394.

- Burch, Noël. Marcel L'Herbier. Paris: Seghers, 1973. [In French]

External links

- L'Inhumaine et Les Arts décoratifs: Marcel L'Herbier's 1925 article in Comoedia, reproduced at Éclairages. [In French]